Only when public conscience is sufficiently awakened to the critical needs of others, only when a huge swathe of the populace is standing up for the basic rights of the poorest among us – only then can we talk of a humanity that shares in any meaningful sense of the word.

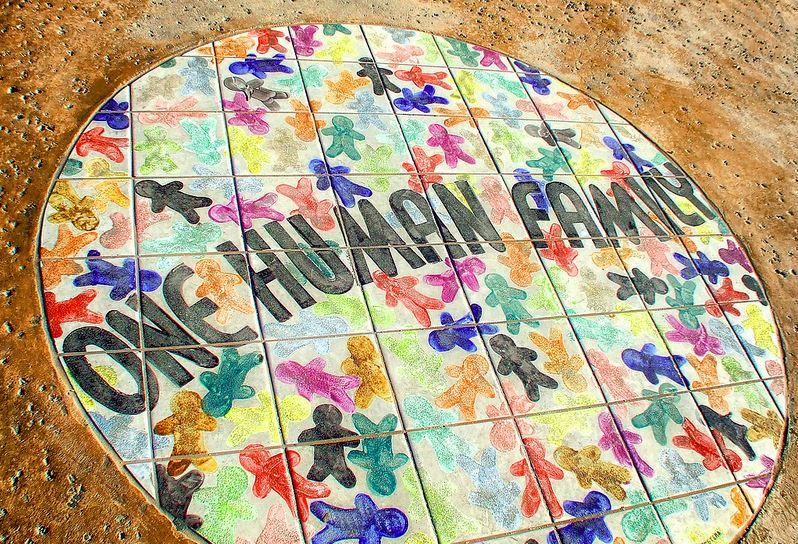

At the end of last week, World Humanitarian Day was observed to honour the work of humanitarian personnel worldwide, and to call for global solidarity with the more than 130 million people who are currently in need of humanitarian assistance in order to survive. It provided an opportunity for people of goodwill to reflect upon the conflict, torture, disease, famine and suffering that is prevalent and worsening in so many countries, especially in light of last year’s #ShareHumanity campaign and the designated theme for this year: ‘One Humanity’. For can we really say that humanity is developing a greater sense of responsibility and global community, and embracing the need to share?

In reality, the lack of sharing in our world has perhaps never appeared more tragic or urgent since the end of the Second World War. Prior to World Humanitarian Day, several reports were released by UN agencies and charities that emphasised the extreme inequalities which could still leave millions of people living in poverty in 2030, despite government promises to ‘leave no-one behind’. An estimated 69 million children will die from mostly preventable causes at current trends, nearly half of which will occur in sub-Saharan Africa where 247 million children - two in every three - are deprived of the basic necessities needed to survive and develop. Behind these statistics also lies a bleak future for many more millions of poor families living in places that the UN Secretary General describes as a “living hell”, such as Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, South Sudan, and Somalia.

There is always plenty of commentary and analysis to show how little of the world’s resources need to be shared, if only to prevent the moral outrage of avoidable deaths from hunger or deprivation-related diseases. For example, the 5.9 million children under the age of five who died from treatable causes in 2015 could have potentially been saved with an additional $25 billion per year, helping the poorest countries to meet their basic health needs. Such a sum could easily be found if all rich nations met their longstanding commitments to give 0.7% of GNI in overseas aid, or if global funds were financed through common-sense policy measures – taxing offshore deposits held by wealthy individuals and corporations, a small tax on financial speculation, diverting military expenditures, and so on.

Indeed, as brought under the spotlight again this week with a second conference on the implementation of an Arms Trade Treaty, global military expenditures cost roughly $1.67 trillion of public funds in 2015 – a major portion of which most taxpayers would, surely, like to see redistributed towards pro-poor investments and ending hunger. Clearly, there is no reason why humanity cannot afford the 0.3% of world income needed to help the poorest countries provide an adequate level of financial security for the least privileged, considering that 870 million of those living in extreme poverty lack any form of social protection.

Even if governments possessed the political will to safeguard these minimal guarantees for everyone, could we describe ourselves as ‘One Humanity’ that shares its planetary resources on the basis of equity and need? Our inefficient systems of overseas aid are far from a ‘sharing economy’, in this respect, and should at least be pooled internationally and raised through an automated mechanism. For now, it’s clear that massive transfers of resources from North to South are central to financing an equitable development agenda and closing the gap between rich and poor nations. But perhaps one day we can envision an end to aid and charity altogether, to be replaced by a democratic system that guarantees the fulfilment of social and economic rights at the international level, funded through global taxes or other sources of innovative funding.

Any such vision will remain a pipedream, so long as the principles underlying domestic systems of sharing and redistribution are being undermined by the increasing commercialisation of our societies. That is why, at the heart of STWR’s proposals, is a call for ordinary people to unite through enormous and peaceful protests that uphold the basic entitlements outlined in Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – for adequate food, housing, healthcare and social security for all. Otherwise, we can expect more high-level conferences on eradicating poverty to come and pass, including the next pledging summit for the Sustainable Development Goals to be held in 2017, while millions more people are left to die prematurely each year.

Only when public conscience is sufficiently awakened to the critical needs of others, only when a huge swathe of the populace is standing up for the basic rights of the poorest among us – only then can we talk of a humanity that shares in any meaningful sense of the word. As STWR’s founder Mohammed Mesbahi has asserted, that is when the terms ‘aid’, ‘charity’ and ‘humanitarian assistance’ may be seen to be psychologically meaningless and absurd, once our world finally shares its plentiful resources more equally among all nations, instead of making non-binding development goals and merely redistributing insufficient amounts of overseas aid.

This editorial was sent out as part of STWR's monthly newsletter: sign up on the front page of sharing.org

Image credit : Fine Art America