A new World Bank report comparing economic growth among different regions in the world ignores key factors in addressing wealth and inequality in Africa—particularly the wealth that is stashed offshore in developed countries, says economist and author Leonce Ndikumana in an interview with The Real News Network.

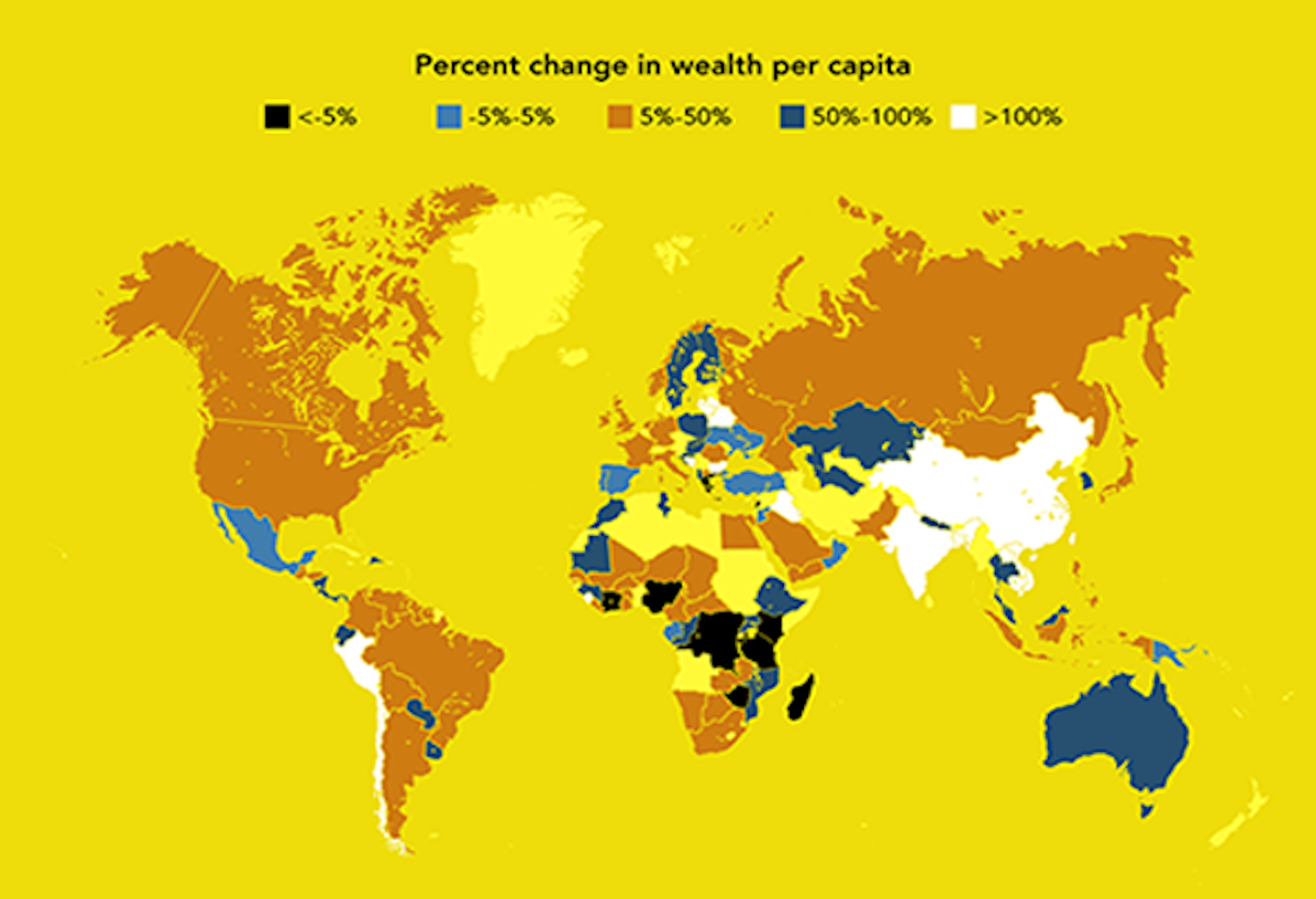

SHARMINI PERIES: It's The Real News Network. I'm Sharmini Peries coming to you from Baltimore. A new World Bank report titled, "The Changing Wealth of Nations" compared the economic growth among different regions in the world since 1995. It found that sub-Saharan Africa has suffered from stagnation and even a loss of wealth while wealthy OECD countries became even wealthier. One important issue that wasn't discussed in the World Bank report is the issue of corruption and its economic effects.

We're going to take that issue up with our next guest, Leonce Ndikumana. He's a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the Director of the African Development Policy Program at the Political Economy Research Institute, PERI. He's also a member of the UN Committee on Development Policy. He co-authored the book, Capital Flight From Africa: Causes, Effects, and Policy Issues. I thank you for joining us, Leonce.

LEONCE NDIKUMANA: Thank you very much for the opportunity.

SHARMINI PERIES: So Leonce, an important dimension of the wealth that the report does not address is Africa's wealth that is stashed away in secrecy in other jurisdictions as a result of accumulation of capital flight over the past decades. And recent evidence of this could be found in the Paradise Papers that was recently released about how the famous wealthy and rich people in the world stash their money in various places to avoid tax. In this case, I guess, when it relates to Africa, this applies as well. So, tell us about how the report evaded that issue.

LEONCE NDIKUMANA: I think this is a very important point that you are making. First of all, just to remind our audience that this report is about measuring countries' wealth across the world, which is an innovation from the traditional practice of focusing on income. That distinction is critically important because when we are measuring, as the World Bank decides to measure wealth in addition to measuring income, it allows us to see how countries are utilizing their resources to create wealth.

But it also allows us to examine, to assess the ability of growth because wealth creation uses resources. So, it allows us to see how countries are utilizing their natural resources, their human capital to create wealth. Now, that's important because then it allows us to examine a number of things which are really not emphasized in the report. One is how that wealth is distributed both among countries and within countries. So, if you consider, if you go beyond the income, which has been used to measure inequality and distribution and consider wealth then you will see actually that according to the evidence that's being produced and also according to the evidence on wealth that I'm going to touch on, you'll see that the traditional view that inequality between African countries say, and the rest of the world, is going to change. In the sense that the wealth that's stashed in offshore financial centers, in developed countries, outside of the continent, is not accounted for by these measures.

That means that these measures are underestimating the wealth of Africa because they are not counting the wealth that has been exported to safe haven, secret jurisdictions and the international financial markets. Which means that the gap between African wealth and other regions may be actually smaller than it is being measured. Within countries, not counting wealth which is stashed abroad, creates again biased measures of inequality because if you are only looking at income that's generated in the country or wealth that is generated and held in another country, ignoring the wealth that is stashed abroad, you are likely to underestimate the inequality within country because the rich, the elite have wealth which is not showing up in national measures. That wealth belongs to them, which means they are much, much wealthier than the ordinary citizen, than national official statistics will tell us.

So, it basically says that we have wealth that's concentrated typically on the top, the very, very top, which is not in the books that the governments and the national institutions are reading to measure national wealth. That's where our analysis of capital flight comes into play. But I wanted to make that clear, that the measurement of wealth, which is an extension of our measurement of progress, by using income is actually a major step ahead that's going to allow us to look at both sustainability of growth in the long run, but also get a much clearer sense of inequality that's not only focused on income, but also includes wealth.

And one other thing about why we need to look at wealth when we measure inequality is because wealth allows you to hedge against or absorb shocks over time. If a household has a lot of wealth and there's a shock to their income, that means that during the recession, during the shock, they can actually survive by drawing on their wealth. Your ordinary citizen in Africa depends on either salary or labor income is not going to be able to absorb the shocks because they don't have the wealth. So, again, measuring wealth makes us see actually, that the gap between the wealthy and the poor is much, much larger than we would have anticipated by looking at just income.

SHARMINI PERIES: What are the implications then, on inequality as a whole as a result of this?

LEONCE NDIKUMANA: Yes. So, first of all, again, between countries, the wealth I'm talking about which is stashed abroad, is actually fueling the economies of the developed world, because the financial systems where this money is held, in London, New York, Bahamas, and all that, that is money that is being used as capital for the development of the developed world. In a sense, African countries are actually financing the development of the developed world. It's a paradox, it's a really, really bad in a sense that we are accustomed to hearing that the rest of the world is supporting Africa by providing aid, by providing foreign investment, but actually this evidence about this massive amount of wealth stashed abroad means that, in contrast, it's African economies that have been fueling the developed world economies.

Our own estimate, thus far, show that from 1970 to 2015 the accumulated amount of capital flight from African countries is an excess of 1.5 trillion. That means that it's bigger than the current total...of African economies. That money could have contributed to capital accommodation in Africa to development by financing public investment, social service delivery. That money is lost to African economies. I want to this point. Even developed countries suffer capital flight. But most of the time, because the capital stashed abroad away by the wealthy, actually cycled back into developed world economies through the financial system. The money that arguably is held in Panama, in Bahamas, in Cayman Islands, is actually intermediated in the banks in London, in Paris, in New York and so on. So, it actually fuels the economies of the developed world. It's a very ironic situation. Where do countries...capital... which are developed countries, developing countries, including African countries, are the ones that are exporting capital to the rest of the world.

That means that the poor is financing the rich. It's really, really unacceptable. Then, within countries, that means that we know that the capital flight benefit from the elite because they are the ones who are able to acquire the capital through either their own earnings, but also by embezzling national wealth. This includes political elite. They are the ones who are able to evade the law, often through corruption. They are the ones who have the connections to get the money out of the country and stash it away from the countries. Here, the African countries are facing in uphill battle, in the sense that these phenomenon is made possible by the complicity of international financial system.

These banks are receiving money that's coming from developing countries with no questions asked. Even though there are rules on the books that require banks to ask what is called due diligence, "Know your customers," those rules are not implemented, which means that makes it possible for this capital flight to go on unabated. So, the whole discussion about capital flight, offshore financial systems implies that the discussion of capital flight and how to curb it is not just an African issue. It's a global issue because even if, as people say, African countries manage to clean up their house, it's not going to stop capital flight until the banks where the money is being held, the countries where the money is being invested in real estate sectors are waiting in their government, are waiting to corporate in support African governments in identifying where the money is going, freezing the money and repatriating it to the country.

Another dimension of how capital flight and offshore financing effects inequality is by undermining the provision of public services. So, basically, the money thats being stolen and stashed out of the continent is money that could have generated a tax income, tax revenue for the government and therefore financing public service like education, health and so on. That means that the poor are not able to access schools, healthcare and other services because there is not sufficient financing for those services. Ironically, the elite, which is benefiting from capital flight, is able to basically resource those services elsewhere. You find that the elite in African countries send their kids to school in Europe, in the US and other rich countries. They are able to source health services abroad. The poor is not able to do that. So, that's an aspect of inequality that we don't get to measure when we only look at income.

SHARMINI PERIES: Alright. Let's turn to corruption and the plunder of the African resources. Of course, it has domestic implications and global dimensions to this corruption. Elaborate on that for us, finally.

LEONCE NDIKUMANA: Yes. So, our analysis, so far has shown the phenomenon of capital flight is facilitated by corruption on both ends. Corruption at the origin, at the source and corruption at the end, which I eluded it to when I talked about the lack of transparency, the lack of accountability in the banking systems in where the money is being stashed. To the source company, it's the corruption that prevents enforcement in the rules of law, enforcement of rules about capital transfers that allows the elite and powerful to be able to smuggle the money abroad in physically acquire the money without any accountability.

So, it means that when we talk about how to curb capital flight, how to prevent further capital hemorrhage of African countries, there is one important factor is to strengthen institutions both domestically but also internationally. But the challenge is this. If you are in a country with bad institutions that are facilitating capital flight, how do you change those institutions? Because the same people who are in charge of those institutions are asked to reform themselves. You don't ask corrupt institutions to reform themselves. That means that we have to think about a coalition, a global coalition against capital flight, against corruption. We need to support foreign entities, foreign government, foreign society groups who are going to support domestic populations in Africa, civil societies in Africa. The academia in Africa that's trying to voice their concerns about this phenomenon because we cannot keep saying lets encourage African countries to go look for more aid, lets encourage African countries to create a better environment for economic investment when money comes in and more money is leaking out of the country, out of the continent, that's not helpful.

SHARMINI PERIES: Alright, Leonce. There is so much more to get into with you about this issue, which I hope we get to do on another occasion. I thank you so much for joining us for today.

LEONCE NDIKUMANA: Thank you very much.

SHARMINI PERIES: And thank you for joining us here on The Real News Network.

Leonce Ndikumana is Professor of economics and Director of the African Development Policy Program at the Political Economy Research Institute (www.peri.umass.edu) at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He is a member of the United Nations Committee on Development Policy, Commissioner on the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation, a visiting Professor at the University of Cape Town, and an Honorary Professor of economics at the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. He has served as Director of Operational Policies and Director of Research at the African Development Bank, and Chief of Macroeconomic Analysis at the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).

Original source: The Real News Network

Image credit: Diplomatizzando, Blogspot