Narrow self-interest makes it unlikely that the global north will commit the resources and know-how necessary to combat the global pandemic — which would also eliminate one of the factors contributing to civil conflict, writes Elizabeth Schmidt for Foreign Policy in Focus.

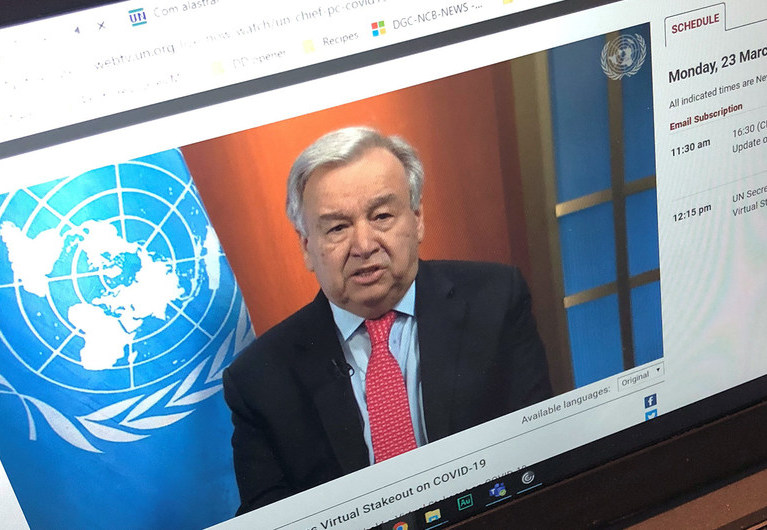

In March 2020, as the COVID-19 virus traversed the planet, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for a global ceasefire to fight the common enemy.

The virus, compounded by the effects of armed conflict, he noted, hit the most vulnerable the hardest. Women, children, the marginalized, and the displaced were among the most defenseless. Hostilities must cease to permit the delivery of aid, the conditions for diplomacy, and ultimately, a resolution to the conflicts.

The response to Guterres’s appeal was discouraging.

Africa, a key battleground on both the pandemic and conflict fronts, had much to gain from a universal ceasefire. However, in the months that followed, little common ground emerged at negotiating tables, where weaker actors made contingent demands that the powerful refused to honor, or on the battlefields, where more powerful parties declined to lay down arms, hoping to achieve a military win.

The Security Council, divided internally, failed to endorse the proposal for more than three months. The United States posed a major obstacle when it insisted that its “counterterrorism” operations be exempted from the ban — a demand that was substantially honored in the final resolution.

Absent political will, the UN resolution will not promote the domestic and international cooperationnecessary to defeat the virus. Evidence from Africa — notably, Mali, Nigeria, and Somalia — suggests that in countries already weakened by poverty, political repression, and violent extremism, the pandemic is intensifying societal tensions and exacerbating rather than quelling civil unrest.

The impact of the virus has highlighted regional inequalities. The collapse of health and economic systems, already under duress, has spurred ethnic scapegoating and xenophobia. Virus containment measures have offered authoritarian states new opportunities to strengthen their powers and repress their opponents. Internal conflicts, which before the pandemic had spilled over borders and attracted foreign military intervention, risk further intensification.

Increasing poverty — and risks of extremism

African economies, already devastated by the impact of climate change, violent conflicts, and global downturns, have been further battered by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has pushed millions of people into extreme poverty.

In Mali, where 3.5 million residents face food insecurity as a result of violent extremism and civil unrest, virus-related economic shutdowns and reduced remittances may threaten 1.3 million people with hunger and impoverish 800,000 more. In Nigeria, the World Bank predicts that COVID-19 will drive oil revenues down by 70 percent this year — fallout from worldwide industrial shutdowns, work-from-home orders, and the grounding of airplanes. The ripple effects may force 5 million more residents into poverty — in a country that already tops global charts for extreme impoverishment.

Economically vulnerable populations, abandoned by their governments, are targets of opportunity for violent extremists — including many that are affiliated with al-Qaeda or the Islamic State. In Somalia, al-Shabaab has established a COVID-19 treatment center and offered protection and basic services where the state has not.

Although courted by extremists, these populations are also the extremists’ greatest victims. In northeastern Nigeria and elsewhere in the Lake Chad region, Boko Haram has refused to close its mosques and schools, rendering local populations more vulnerable to the disease. With state attention and resources diverted to the pandemic, al-Shabaab and Boko Haram have stepped up their attacks, increasing the number of internally displaced persons and refugees and provoking multinational counter-offensives that have killed countless civilians.

Scapegoating and repression

Fear and hardship provoked by the disease have fueled a rise in ethno-nationalism, xenophobia, hate speech, and the targeting of refugees, migrants, and other marginalized populations.

Pandemic-induced border closures and movement restrictions render these populations even more vulnerable. In Yemen, where war and the COVID-19 pandemic have decimated the health system, Houthi militias have blamed migrants from Ethiopia and other parts of the Greater Horn for the virus’s spread and forced thousands into the desert without water or food. Other African migrants, pushed into Saudi Arabia, have been beaten and imprisoned.

If fear and hardship have stoked the flames, measures taken to impede the virus’s spread may generate further instability. Some governments have declared states of emergency that have broadened executive powers and opened the door to greater human rights abuses by authoritarian regimes.

Across the continent, police have violently attacked civilians who ignored lockdown rules or protestedvirus-induced price gouging. Informal sector workers have been disproportionately targeted, and migrants from other countries have been denied services and assistance. Elections postponed due to health concerns have allowed some leaders to extend their terms; others have used the crisis to expand their powers. In Somalia, where elections have been delayed indefinitely, opposition forces have cried foul and warned that consequences will follow.

A recipe for instability

The realization that we are all in this together has prompted a call for increased international cooperation to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. The UN’s call for a global ceasefire is one step in the right direction. However, the world’s response has been weak.

In Africa, warring parties and international mediators have made little progress on the diplomatic front. In Mali, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), al-Qaeda’s regional affiliate, is willing to negotiate with the government — and may even collaborate against the Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS). However, it will begin talks only if foreign troops depart. The dominant powers have little interest in this option, and the UN resolution doesn’t force their hand - its ban excludes counterterrorism operations focused on al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and their affiliates.

The entrenchment of ethno-nationalism, xenophobia, and narrow self-interest in some of the world’s wealthiest nations makes it unlikely that the global north will commit the resources and know-how necessary to combat the virus successfully — which would eliminate one of the factors contributing to civil conflict.

While African actors on the ground are working to develop effective solutions, they are up against formidable odds. If those with power fail to act, poverty, repression, divisions within and between countries, and the long history of detrimental foreign intervention make further instability, rather than international cooperation, the most likely outcome of Africa’s COVID-19 crisis.

Elizabeth Schmidt is professor emeritus of history at Loyola University Maryland and the author of six books about Africa.

Original source: Foreign Policy In Focus

Image credit: Daniel Dickinson, UN News