Key points:

-

Official Development Assistance (ODA) is the main mechanism currently used by the international community for sharing financial resources globally, but it is severely compromised by the self-interest of donor countries and often fails to contribute to long-term development.

-

Although the quality of aid is in need of extensive reform, the quantity of aid donated is still enormously insufficient. Increasing ODA to 1% of GNI in the short term could raise an additional $297.5bn per year, much more in line with the urgent needs of developing countries.

-

Foreign aid is dwarfed by the net flow of financial resources from the Global South to the North, which undermines its effectiveness in producing any significant degree of redistribution to developing countries.

-

Ending poverty will ultimately require helping low-income countries to develop their tax and social protection systems, alongside extensive reforms of the global economy to distribute wealth and power more equally between and within countries.

Despite decades of repeated commitments by donor countries, attempts to share even a tiny fraction of their financial resources with poorer nations remain inexcusably feeble and highly problematic. It is widely acknowledged that development aid does not constitute a sustainable solution to poverty eradication, which urgently requires extensive reforms to the global economy so that wealth and power is more equally distributed between and within nations. But if systems of aid are adequately reformed and the quantities donated substantially increased, Official Development Assistance (ODA) could play a much greater role in saving lives and helping people to lift themselves out of poverty.

In recent history, the practice of sending aid to overseas countries began with reconstruction efforts after the Second World War when the United States initiated a large-scale program to help rebuild Europe known as the Marshall Plan. Against a background of decolonisation and ‘under-development' in the Global South, the World Bank published a report by the Pearson Commission in 1969 that reviewed the past 20 years of development assistance. The report recommended that official aid should be equivalent to 0.7% of the gross national income (GNI) of donor countries, and that both the government and private sector should supplement this with additional finance to ensure total assistance equalled 1% of GNI.[1] In 1970, the UN General Assembly adopted a Resolution including the goal that each advanced country will progressively increase its ODA and exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7% of its GNI by the middle of the decade.[2]

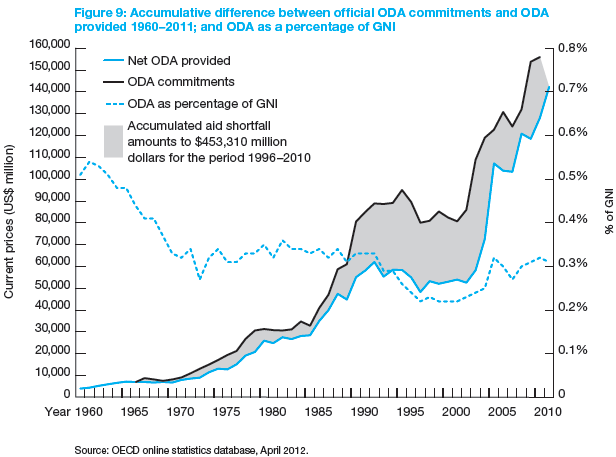

More than 40 years later, this target continues to beleaguer donor countries whose combined donations of aid still average less than half of the universally-agreed target [see figure 1]. The pledge has been regularly reiterated at various high-level international fora, including the International Conference on Financing for Development in Monterrey in 2002. Following the high-profile ‘Make Poverty History' campaign in 2005, G8 leaders again committed to significant increases in aid during their Gleneagles Summit, including a pledge to double aid to Africa. Yet only 61% of the promised increases to sub-Saharan Africa were delivered by 2010 when the commitments were due to be met, at a time when millions more people were being pushed into poverty by the food and financial crises.[3]

In 2011, donor countries provided $133.5bn of net ODA, representing 0.31% of their combined gross national income - a drop of nearly 3% compared to 2010, and the first overall decrease for 14 years.[4]This represented a fall in real terms (inflation-adjusted) of $3.4bn, an amount that Oxfam calculated would be enough to provide a full year of treatment for half of the children infected with HIV.[5] In some OECD countries such as Italy, Japan and the United States, the current rate of ODA is lower than 0.2% of GNI.[6] By failing to meet their long-standing commitment to donate 0.7% of GNI, rich countries deprived the developing world of over $167.5bn in 2011 alone.[7] Although rich countries have donated over $3tn in ODA since 1970, the accumulated total shortfall in aid since 1970 (when the target of 0.7% was set) amounts to over $4.37tn. The total aid delivered over this period is therefore less than half of the promised amounts.[8] On current trends, donors will not collectively hit the 0.7% target for a further 50 years, until 2062.[9]

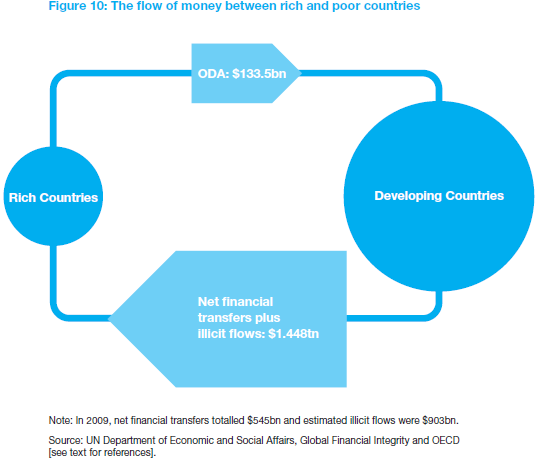

In stark comparison, rich countries mobilised $12tn within the space of a few months to bail out a small number of banks during the global financial crisis of 2008. ODA is also dwarfed by the flow of financial resources from the Global South to industrialised countries in the North. According to estimates from the UN, developing countries as a group provided a net transfer of $545bn to developed countries in 2009.[10] This net outflow is further exacerbated by illicit capital flows from developing countries to the rich world that totalled $903bn in the same year, which includes efforts to shelter wealth from tax authorities and the transfer of money earned through various illegal activities.[11] In comparison to these enormous waves of capital being haemorrhaged from poor to rich countries, development aid is rendered futile in producing any significant degree of net global redistribution [see figure 10].

Global Redistribution

Many analysts argue that modern development assistance is essentially a form of neo-colonialism, and there is widespread agreement that the international aid architecture must be significantly reformed to address its inherent flaws.[12] It is now well recognised that long-term dependency on ODA can be detrimental to nations, and more ODA needs to be directed to helping poorer countries to develop and manage their own economies [see box 13].

Despite these entrenched problems, foreign aid is one of the only mechanisms used by the international community to redistribute financial resources to developing countries [see note].[13] Given that at least 41,000 people die every single day from poverty-related deaths globally,[14] it is clear that ODA has a real potential to save lives and help prevent extreme deprivation. Although aid alone cannot resolve the problem of poverty or redress the extreme imbalance of wealth in the world, it must be reformed and strengthened in the immediate term until it can eventually be replaced by more effective and genuinely redistributive global arrangements in the future.

There can be no justification for advanced economies redistributing so little of their national incomes to assist those living in extreme poverty around the world. Not only is it entirely feasible for donor countries to give 0.7% of their GNI in official aid, the target could be significantly increased to bring it more in line with urgent requirements. Some European countries have set credible timetables for reaching the 0.7% target by 2015, but Luxembourg, Denmark and the Netherlands have already exceeded the 0.7 target, while Sweden and Norway donate 1% or more of their GNI [see table 4].[15]

In the wake of a global economic crisis that is exacting a disproportionate blow on poor people and the finances of low-income countries, a more generous vision of international aid is sorely needed. If all donor countries committed 1% of their income to development assistance, aid flows would more than triple to almost $431bn a year, raising an additional $297.5bn annually - a figure more commensurate with the pressing requirements of many developing countries today.[16] After more than forty years of failed commitments on aid, civil society must continue to demand that rich nations reform the way aid is donated and used, and call on donors to make the redistribution of at least 1% of their national incomes an integral part of government policy in the immediate term.

How much revenue could be mobilised

The following estimates are based on OECD Official Development Aid figures for 2011 when donor countries gave a total of $133.5bn in ODA, equal to 0.31% of combined GNI of DAC member countries.

Increasing ODA to 0.7% of GNI ($301bn) would raise an additional $167.5bn annually.[17]

Increasing ODA to 1.0% of GNI ($430.6bn) would raise an additional $297.5bn annually.[18]

Box 13: What's wrong with international aid?

Development aid remains a highly problematic way of redistributing financial resources, mainly as a consequence of the self-interest of donor countries and the way in which aid is administered and used. Some of the main criticisms of Official Development Assistance (ODA) include:

-

Quantity: Aid-giving remains voluntary, and there is no system in place on the international level to ensure that the amounts given equate to those needed. Rich country governments actually give less today as a share of their total wealth than they did 40 years ago (0.51% of GNI in the late 1960s, compared to around 0.3% today).[19] There remains no guarantee that development assistance will be spent on the neediest people in the poorest countries, as demonstrated by the precipitous falls in aid to agriculture over the last 20 years despite the fact that most of the world's poorest live in rural areas. Donors have repeatedly pledged to increase their aid for more than 35 years, but no penalties are imposed by the international community when these promises are broken.[20]

-

Conditionality: Despite years of campaigning by pressure groups, the use of policy conditionality remains widely linked to aid disbursements. Conditions designed to induce policy change can have a broad-ranging impact on the functioning of the state, particularly through policies associated with trade liberalisation, the elimination of subsidies and privatisation. Although there are now donor-led processes attempting to increase the ownership of governments over their economic policy decisions (in particular the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper approach led by the IMF and World Bank), rich countries continue to seek to influence developing country choices with the aid they provide. In 2009, the European Commission reported that only five European governments out of 27 had reduced the number of their policy conditions.[21]

-

Tied aid: Some donors continue to tie aid to the use of goods and services in their own countries. This may involve directly buying preferential treatment for companies based in donor countries, or else using conditions to influence recipient country policy and make trade rules and the investment climate more suitable for domestic corporations. As much as 40% of all aid, excluding food aid and technical assistance, is still tied to commercial conditions despite donor commitments to untie all their aid to the least-developed countries. Italy and the USA are among the worst culprits, spending upwards of 70% of aid on domestic firms and organisations.[22] Even countries that tie their aid only moderately, such as Germany and the Netherlands, receive significant returns from their aid donations. A study by Switzerland's foreign aid department suggests that for every 100 Swiss Francs spent on aid, the Swiss economy gets back about 160 Swiss Francs.[23]

-

Phantom aid: Many forms of assistance are included in official aid statistics which do not in fact contribute to improving the lives of poor people. This includes aid that is double counted as debt relief; billions of dollars that is spent on over-priced and ineffective technical assistance (outside expertise such as consultants, research and training); the aid spent on immigration-related spending in the donor country; excessive administration costs; or the resources lost through the costs to recipients of poor donor co-ordination.[24] According to the latest figures from ActionAid, still 45% of aid disbursed in 2009 was not ‘real' aid that contributes to long term development.[25]

-

Politically-motivated aid: Political and strategic considerations are well known to determine key aid relationships, most notoriously for the US which continues to view USAID as a key plank of foreign policy and national security concerns.[26] During the Cold War period both bilateral and multilateral aid was openly driven by political interests, and former colonial relationships still strongly influence aid relationships today. The discourse on the geopolitical motivations for ODA tends to focus on two main issues; firstly, politically-driven aid is not necessarily going to the countries that need it most.[27] And secondly, self-interested political objectives mean that such aid by its nature is less effective at promoting growth and reducing poverty.[28]

-

Problematic food aid: The transfer of food items from one country to another for development purposes has declined in quantity and as a percentage of total aid in recent decades. However, this practice is still widely criticised for subsidising domestic interests in the donor country rather than helping the poor abroad.[29] A large proportion of food aid is tied to domestic procurement and shipping, particularly in the US - the world's largest food aid provider.[30] The US also stands accused of using its food aid programme to push genetically modified foods on developing countries, and of trying to create future commercial markets by changing local tastes and preferences.[31] Furthermore, direct transfers of food aid are often badly timed and risk pushing down prices and discouraging production in recipient countries, with severe effects on future food security.[32]

-

Aid dependency: In recent years, the discourse on ODA has increasingly focused on the problem of aid dependency. Many poor countries are considered dependent on aid when they require external assistance from donors to perform many of the core functions of the state, including the delivery of basic public services. Aid dependency is a major concern for the following reasons: it can result in a loss of policy space for governments to design and implement their own national development policies; it can undermine the social contract between citizens and the state, as governments are less accountable to ordinary people for delivering public services; and it can undermine the predictability of government spending and affect long-term planning, as aid flows are more volatile than revenues generated from domestic sources.[33] Figures suggest that aid dependency has fallen between 2000 and 2009, but still 30 of the less industrialised countries rely on aid for 30% or more of their expenditure.[34]

Reforming and scaling up overseas aid

Until recently, there were some signs of progress in government commitments to increase the amount of ODA donated to poor countries, with aid levels reaching a historic high in 2010 following a long trend of annual increases. Of the 15 European Union countries that are members of the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-DAC), eight of them surpassed a goal set in 2005 to allocate a minimum of 0.51% of their GNI to ODA by 2010.[35] Although serious doubts surround the effectiveness and relevance of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) framework for long-term poverty reduction, many analysts have argued that the MDGs helped to target aid more effectively and increase the focus on accountability among donors, especially at the G8.[36] According to calculations by ActionAid, the amount of ‘real' aid provided by donors - that which is targeted at the poorest people and allows the recipient country the space to lead its own development plans - has also increased, if only marginally, from 51% to 55% of total aid flows since 2006.[37]

However, the ODA figures for 2011 cast a shadow over these marginally positive developments. NGOs expressed particular concern that aid has fallen to the world's 48 poorest countries, along with a fall in bilateral aid to sub-Saharan Africa - the poorest region of the world. Campaigners also said that "alarm bells should be ringing across Europe" following the confirmation that 12 EU countries have cut overseas aid, including some that have weathered the economic crisis more easily, such as Austria and France.[38] Cuts to aid budgets in Spain and Greece, where fiscal tightening policies are severe, were in the order of 40%. Although some EU countries managed to increase their aid, many countries are seeking to further reduce their ODA budgets this year, and it looks increasingly improbable that the EU will hit its official 0.7% target by 2015. For non-EU developed countries such as the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, such a target is a pipe dream judged by current standards.[39]

A chronic lack of ambition

Notwithstanding the wider problems of aid effectiveness and the unequal power relationships between donor and recipient governments, the quantity of aid donated falls far short of the amount urgently needed to reach the MDGs - and will continue to be insufficient even if G8 donors meet all their existing and future promises on aid. Although the MDGs are widely considered to be grossly inadequate targets for ending poverty, it is also true that ‘good quality' aid can make a real impact on poverty reduction, especially when provided in sufficient quantities. For example, if governments had provided all the aid they committed to in 1970, Oxfam calculated that extreme poverty could have been ended 22 times over - a prolonged failure they describe as the greatest missed opportunity in history.[40]

Against the backdrop of a worsening global financial crisis and widespread austerity, there is a great risk that rich countries will continue to cut investments in effective programmes that benefit the world's poorest people. Many development organisations now fear that both public and political support for increased aid has passed its peak owing to the financial downturn and domestic austerity measures, as well as the perception that many developing countries are experiencing high economic growth and no longer need the same level of support. In the UK, the House of Lords economics affairs committee even published a report that called to abandon the 0.7% target for overall aid spending that was previously enshrined in legislation - with cross-party political support - in 2010.[41]

Aid advocates challenge these attitudes, however, particularly by pointing out that aid is a tiny part of national budgets and will have no discernible impact on deficits if cut.[42] Public support for ODA also tends to rise when people are informed of how little governments actually spend on aid, compared to other priorities.[43] As many NGOs and development analysts maintain, life-saving programmes in poor countries are critically affected by reducing aid, especially when people in developing countries are struggling to cope with the impacts of the financial crisis.[44]

Numerous reports and campaigns since the 0.7% UN resolution have advocated for an increase in official aid to 1% of GNI or more, including the influential proposal by the Brandt Commission in 1980 which also recommended an immediate and large-scale transfer of resources from North to South.[45]The Network of Spiritual Progressives go much further and advocate that the US government spends 1 to 2% of GDP on foreign aid for the next 20 years in order to eliminate poverty once and for all and heal the environmental crisis. If all the advanced industrialised countries committed to a ‘Global Marshall Plan' along such lines, they estimate that the costs could reach 3 to 5% of world GDP.[46]

Transforming the international aid architecture

Historically, concerned citizens have tended to focus on the need to increase only the quantity of aid provided by donors. Increasingly, however, civil society is mounting pressure on donors to improve the quality of their aid by freeing it from political and commercial interests, removing damaging conditions attached to its provision, and mitigating the negative impacts it can have on local communities and national development [see box].

Although governments have officially recognised the problems plaguing aid by signing up to the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness since 2005, the process fails to give a meaningful role for southern countries in assessing donor progress towards a set of relatively weak targets.[47] Current reform initiatives by the OECD-DAC, United Nations, World Bank and other donors have failed to resolve the entrenched geo-political and commercial interests that prevent aid from realising its potential to forge a more equal, balanced and stable global system.

In the longer term, donors need to move beyond a ‘targeted' approach to poverty reduction and embrace a more comprehensive and sustainable model of development based on universal social protection and nationally-anchored production and consumption.[48] The recent shift within the development community to focus on helping low-income countries develop their domestic taxation systems is an important step in the right direction, and one that demands further support from donors and international agencies [see section of this report on international tax justice].[49]

It has long been argued that aid should be pooled at the international level and channelled through a more representative body, such as a World Development Fund managed by the United Nations, in order to remove the short-term political interests of donors and ensure that ODA is redistributed efficiently through binding long-term commitments.[50] Some analysts are calling for more genuinely redistributive systems to replace ODA as the primary method of funding development, such as those based on a global system of progressive and redistributive taxation.[51] Ultimately, an end to world poverty will never happen without a reformed architecture of global governance, a shift in power relations from North to South, and major political-institutional changes in the global economy.

Learn more and get involved

AidFlows: Flash graphics on how much development aid is provided and received around the world, provided by the OECD, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. Users can select individual donors (providing the aid) and beneficiaries (receiving the aid) to track the sources and uses of aid funding. <www.aidflows.org>

AID/WATCH: An independent watchdog on aid, trade and debt. Based in Australia and working with communities in the Global South, they challenge practices which undermine the ability of communities to determine their own futures, and promote development alternatives based on social and environmental justice. <www.aidwatch.org.au>

The DATA Report 2012: For five years, the ONE campaign's annual DATA reports monitored the historic promises that the G8 and EU made to sub-Saharan Africa at the Gleneagles Summit in 2005. The latest report assesses Europe's progress in keeping its promises for aid increases and aid effectiveness. <www.one.org/data>

Does foreign aid really work?: Book by Roger Riddle with a comprehensive analysis of the aid system, and practical conclusions for how to make aid an effective force for good. Published by OUP Oxford, 2007.

The Centre for Global Development: The Center's work on aid effectiveness focuses on the policies and practices of bilateral and multilateral donors. It includes analysing existing programs, monitoring donor innovations, and designing and promoting fresh approaches to deliver aid. <www.cgdev.org/section/topics/aid_effectiveness>

The End of Poverty: How We Can Make it Happen in Our Lifetime: Book by Jeffrey D. Sachs based on his plan to end global extreme poverty within 20 years. Controversial prescriptions, but useful context and data. Published by Penguin, 2005.

Global Issues on Foreign Aid for Development Assistance: Resources and analysis on the history of aid, including foreign aid numbers in charts and graphs, compiled by Anup Shah. <www.globalissues.org/article/35/foreign-aid-development-assistance>

OECD statistics portal: The latest ODA data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, an international economic organisation of 34 countries founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade. <www.oecd.org/statsportal>

OneWorld's foreign aid guide: A backgrounder on aid sources and statistics; aids critics; aids effectiveness and aids broken promises. <www.uk.oneworld.net/guides/aid>

Reality of Aid Network: A major North/South international non-governmental initiative focusing exclusively on analysis and lobbying for poverty eradication policies and practices in the international aid regime. Since 2000, the RoA publishes a major biennial thematic report assessing aid effectiveness for poverty reduction. <www.realityofaid.org>

The Story of Official Development Assistance (pdf): A history of the DAC by Helmut Führer, former Director of the OECD's Development Co-operation Directorate. <www.oecd.org/dataoecd/3/39/1896816.pdf>

UN Millennium Project: Commissioned by the United Nations Secretary-General in 2002 to recommend a concrete action plan for the world to reverse the grinding poverty, hunger and disease affecting billions of people. <www.unmillenniumproject.org>

Notes:

[1] Lester B. Pearson et al, Commission on International Development: Partners in development, New York, Praeger, 1969.

[2] DAC Journal, History of the 0.7% ODA Target, 2002, Vol 3 No 4, pp. III-9, III-11.

[3] ONE Campaign, The DATA Report 2011, May 2011, pp. 6-7.

[4] OECD, ‘Development: Aid to developing countries falls because of global recession', 4th April 2012.

[5] Oxfam, ‘First global aid cut in 14 years will cost lives and must be reversed', 4th April 2012.

[6] OECD iLibrary, Development aid: Net official development assistance (ODA), Net disbursements at current prices and exchange rates, 2011 [table], 13th April 2011, <www.oecd-ilibrary.org>

[7] Calculations based on OECD Official Development Aid figures for 2011 when donor countries gave a total of $133.5bn in ODA, equal to 0.31% of combined GNI of DAC member countries. If the 0.7% of GNI target had been met, total ODA would have reached $301bn in 2011, equivalent to an additional sum of $167.5bn.

[8] Calculated by Anup Shah, based on OECD figures up to 2011. See Global Issues, Official global foreign aid shortfall: $4tn, updated 8th April 2012, <www.globalissues.org>

[9] Oxfam, First global aid cut in 14 years..., op cit.

[10] Note: The net transfer of financial resources measures the total receipts of financial and other resource inflows from abroad and foreign investment income minus total resource outflows, including increases in foreign reserves and foreign investment income payments. See: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA), World Economic Situation and Prospects 2010, New York: 2010, table III.1, p. 73.

[11] Dev Kar and Sarah Freitas, Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries Over the Decade Ending 2009, Global Financial Integrity, December 2011.

[12] Yash Tandon, Ending Aid Dependence, Fahamu, 2008.

[13] Note: Technically, other forms of international redistribution could include loans provided by international institutions such as the IMF, as well as foreign direct investment and international trade.

[14] Figures based on World Health Organization, Cause-specific mortality: regional estimates for 2008, Health Statistics and Health Information Systems, <www.who.int/healthinfo/> Note: Only communicable, maternal, perinatal, and nutritional diseases have been considered for this analysis, referred to as ‘Group I' causes by the WHO. Ninety six percent of all deaths from these causes occur in low- and middle-income countries and are considered largely preventable.

[15] OECD data for 2011, op cit. In the case of the Netherlands, the 0.7% of GNI target was still reached despite sharp cuts to its aid budget in 2011, although further steep cuts are planned for 2013.

[16] OECD data for 2011, op cit.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] OECD iLibrary stats.

[20] Roger C. Riddel, ‘Is aid working? Is this the right question to be asking?', OpenDemocracy, 20th November 2009, <www.opendemocracy.net>

[21] CONCORD, Lighten the Load: In a time of crisis, European aid has never been more important, 2009, p.28.

[22] ActionAid, Real Aid 2: Making Technical Assistance Work, 2006, p. 26.

[23] Gilles Carbonnier and Milad Zarin-Nejadan, Effets économiques de l'aide publique au développement en Suisse, Etude2006, Berne: Direction du développement et de la coopération, 2008.

[24] Romilly Greenhill and Patrick Watt, ‘Real Aid: An Agenda for Making Aid Work', ActionAid International, June 2005.

[25] ActionAid, Real Aid 3: Ending Aid Dependency, September 2011, p. 44.

[26] Jonathan Glennie, The Trouble With Aid: Why Less Could Mean More for Africa, Zed Books, 2008, pp. 108-110.

[27] David Sogge, Give and Take: What's the Matter with Foreign Aid?, Zed Books, 2002.

[28] Alberto Alesina and David Dollar, ‘Who gives foreign aid to whom and why?', Journal of Economic Growth, 5 (1), 2000, pp. 33-63.

[29] Food and Agriculture Organisation, State of Food and Agriculture 2006 - Food Aid for Food Security?, Rome, 2006.

[30] Frederic Mousseau, Food Aid or Food Sovereignty? Ending World Hunger in our Time, Oakland Institute, 2005.

[31] Sophia Murphy, Food Aid Emergency, IATP, August 7, 2008.

[32] Katarina Wahlberg, Food Aid for the Hungry?, Global Policy Forum, January 2008, p.4

[33] ActionAid, Real Aid 3, op cit, pp. 17-18.

[34] Ibid. See: Table of 20 Most Aid Dependent Countries in 2000 and 2009, p. 20.

[35] United Nations, The Millennium Development Goals Report 2011, New York, 2011, p. 59.

[36] See Poverty in Focus, The MDGs and Beyond: Pro-Poor Policy in a Changing World, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, Poverty Practice, Bureau for Development Policy, UNDP, Number 19, January 2010.

[37] ActionAid, Real Aid 3: Ending Aid Dependency, September 2011.

[38] ONE, ‘Aid figures reveal worrying trend', Press release, 4th April 2012.

[39] OECD, Net ODA - ODA/GNI in 2011, <http://webnet.oecd.org/oda2011>

[40] Oxfam, 21st Century Aid: Recognising Success and Tackling Failure, April 2010, p. 48. See note 164 for calculation, based on 2005 levels of extreme poverty and cost estimates for meeting the Millennium Development Goals.

[41] Economic Affairs Committee, The Economic Impact and Effectiveness of Development Aid, 20th March 2012, <www.parliament.uk>

[42] Oxfam, First global aid cut in 14 years..., op cit.

[43] WorldPublicOpinion.org, ‘American Public Opinion on Foreign Aid Questionnaire', 30th November 2010; The ONE Campaign, UK Aid: View from the street, 6th June 2011 [video], <www.youtube.com>

[44] Jonathan Glennie, ‘Rich Countries Should Be Increasing, Not Reducing, Aid', The Guardian, 21st October 2010.

[45] The Brandt Commission, North-South: A Programme for Survival, MIT Press, 1980.

[46] Network of Spiritual Progressives, ‘The Global Marshall Plan: A National Security strategy of Generosity and Care', <www.spiritualprogressives.org>

[47] ActionAid, Real Aid 2: Making Technical Assistance Work, 2006, see box 2, p. 18.

[48] For example, see: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Combating Poverty and Inequality: Structural Change, Social Policy and Politics, Geneva: 3rd September 2010.

[49] Deborah Itriago, Progressive Taxation: Towards fair tax policies, Oxfam International, September 2011.

[50] For example, in 1980 the Brandt Commission said the time had already passed for aid to be raised through some sort of automatic mechanism. See Roger C. Riddell, Does Foreign Aid Really Work?, Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 398.

[51] For example, see: Valpy FitzGerald, ‘Global capital markets, direct taxation and the redistribution of income', Oxford University, First draft of paper presented to the conference ‘Economic Policies of the New Thinking in Economics' at St Catherine's College, Cambridge, 14th April 2011.

Image credit: Panos Images