Despite billions spent in official aid to fight poverty, the number of poor people in the world is not diminishing. And Latin America remains the most unequal region in the world, writes Carlos March for openDemocracy.

Inequality is the worst kind of poverty, because inequality is precisely what causes it. Measuring poverty and allocating budget lines in the absence of public policies against inequality is like applying a tourniquet below the wound. According to the OECD, $ 134 billion in official aid were spent in 2013 to fight poverty. The number of poor people in the world, however, is not diminishing.

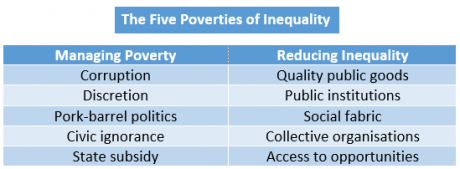

Poverty for an individual is the lack of what he or she needs to live. Inequality in a society is the structural lack that generates poverty, which is due to five causes:

- lack of quality public goods;

- absence of public institutions;

- lack of social fabric;

- inability to organize collectively;

- no access to opportunities.

When, in a context of inequality - Latin America is the most unequal region in the world - government programs are restricted to implementing assistance plans and public policies are not structured to address the five causes mentioned above, the end result is poverty being managed in a way that perpetuates it rather than management aimed at putting an end to the inequality that generates it.

The first factor of inequality is when a sector of the population lives in a context lacking quality public goods, because a society that lacks these goods and services - which should be available to all equally, both in quantity and quality - is actually denying large-scale social inclusion. A hospital is a public good not because the state manages it, but because both the person with the largest resources and the person in most need in a community get the same quality of service, regardless of who manages it.

If the health system provides poor attention to the vulnerable segments of society and directs people to the private system for quality care, then only the most affluent sectors will be able to afford it and healthcare will no longer be a public good, in so far as it no longer guarantees the same living standard quality to the population as a whole. A government's first policy measure should thus be the setting up of a collaboration agreement with both civil society and the business sector to produce, manage, distribute, and safeguard quality public goods. All three actors contribute distinctive elements to the generation of these goods: the state adds scale, the business sector quality, and social organizations specificity.

The lack of public institutions is another decisive factor of inequality, since those who suffer most from it are the sectors who live in poverty and have no way of preventing the impact of discretion in the allocation of public resources, of concentration of power and institutional abuse, of welfare provision (a blend of assistance and cynicism), cronyism, structural corruption and organized crime from damaging their living conditions. There cannot be zero poverty if there is no zero corruption and zero discretion. If we are to deal with, and solve, institutional weakness, tools of participatory democracy should be introduced and citizens empowered to demand full enforcement of the rule of law, while businessmen should actively assume their role as citizens.

Another characteristic of inequality is the lack of social fabric. The poor sectors’ social links are restricted to a reduced environment, they engage in isolated socio-economic relationships, and they have limited or even non-existent contacts with those who facilitate access to the social ladder. The lack of quality links undermines the consolidation of upward social mobility and leaves people exposed, lacking buffer spaces and containment areas, facing the abuse of power of both public institutions and the powers that be. The state should create the necessary conditions for public spaces and public goods and services to be the place where cross-cutting social and economic links are made - as used to be the case with the Latin American public education system which shaped, for example, the Argentine middle class.

The inability of vulnerable sectors to organize collectively is another inequality factor that contributes to their being in poverty. Fragmented populations, which are the victims of pork-barrel politics, which are incapable of creating the social conditions for organizing to defend their rights, control the discretion of those in charge and influence the quality of collective life, are doomed to being defined as objects of assistance by the people in charge who break the social fabric.

The state should promote civic education aiming at providing the community with the capacity to organize collectively as a subject for change, capable of defining its own quality of life, of influencing the quality of collective life, and of setting limits to the discretionary power of the people in charge. In addition, the state should facilitate the formalization of social organizations through changes in the current legal, fiscal and labour regulations, which are responsible for keeping 90% of these organizations in the informal sector, thus preventing them from acquiring legal status and meeting the requirements for receiving donations.

The fifth aspect of inequality has to do with the denial of access to opportunities. Public policies should provide the means for the members of a community to access equitably the capacities which ensure high standards of human dignity, guaranteed respect for human rights, and quality public services. Restoring the quality of the public education system is essential, because education is the primary source of equitable access to opportunities.

The situation requires that fight against poverty should take the form of disarmament of the system of inequality: offering quality public goods, establishing democratic institutions, promoting the building of social networks, ensuring the capacity to organize collectively, and guaranteeing access to opportunities.

In 1965 the world population was 3.3 billion. Today, it is 7.3 billion, and the population living below the poverty line is nearly 4 billion. That is to say, the number of poor people in the world amounts to the population increase of the last fifty years - the figure shows that despite the millions of dollars invested in fighting poverty, we have actually been unable to increase the number of people enjoying quality living standards.

So, it is clear that poverty will only be properly fought when governments stop addressing it as a problem of the poor, and start defining public policies from the perspective of inequality – which, in turn, should be addressed as a state problem.

Original source: Democracia Abierta

Photo credit: Luis Pérez/Wikimedia Commons