A new report by leading sustainability experts has reaffirmed the case for a paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems – fundamental to which is a call for redistributing power back into the hands of those who feed the world.

An alternative vision of farming and food systems has long been upheld by civil society groups and small-scale producers around the world, based on the science of agroecology and the broader framework of food sovereignty. But while many reports and studies have shown how less intensive, diversified and sustainable farming methods can have far better outcomes than today’s corporate-dominated model of industrial agriculture, the question remains as to how we can make the shift towards agroecological systems on a global scale.

A new report by The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) has therefore attempted to fill a gap in these research findings, mapping out the common leverage points for unleashing such a radical transition. Led by the former UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Olivier De Schutter, a group of 20 leading agronomists and sustainability experts conclude that modern agriculture is failing to sustain the people and resources on which it relies, and has “come to represent an existential threat to itself”.

The first section of the report cites the overwhelming evidence in favour of a major transformation of our food systems, from the environmental and socio-economic issues to the question of global food supplies, which the authors crucially argue will not be greatly affected by moving away from industrial agriculture. The report strongly contends that what’s needed is not a “tweaking” of monocultural production systems or “incremental shifts” towards more sustainable farming practices, but a fundamental paradigm shift that addresses the underlying dynamics and power relations that are at the root of the agricultural crisis.

However, the scale of the challenge is clear in the report’s second section, which outlines the vicious circles and “lock-ins” that keep industrial agriculture in place, regardless of its negative outcomes. Some of these factors relate to the political structures governing food systems, such as the web of interlocking market and political incentives that are tailored to large-scale farming, and the increasing orientation of agriculture to international trade. The report also looks at other conceptual barriers and framing issues that serve to lock in the technology-oriented, highly specialised model of farming that is based on “compartmentalised” and short-term thinking within the political and business communities.

Feeding the world?

Of particular significance is what the authors term “feed the world” narratives that continue to inform public policy, based on a narrow vision of food security understood in terms of delivering sufficient net calories at the global level. These productivity-focused narratives tend to ignore the fact that hunger is fundamentally a distributional question tied to poverty, social exclusion and other factors that prevent sufficient access to food, as emphasised by statistics from the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organisation. Impressive productivity gains in industrial systems have clearly not translated into global food security by any measure, with 795 million estimated to be suffering from hunger in 2015, and 2 billion people afflicted by the “hidden hunger” of micronutrient deficiencies.

Furthermore, narratives about “feeding the world” through increased net production levels also serve to deflect attention away from the failings of industrial agriculture, thus reinforcing the dominant paradigm. In this light, the report cites the initiative called the “New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition in Africa” (NAFSN) that was launched by G8 countries in 2012 with the noble aim of improving the lives of smallholder farmers and lifting 50 million out of poverty by 2050. By focusing on integrating smallholders into agribusiness-led global supply chains through outgrower schemes, the NAFSN initiative ignores the power imbalances and livelihood stresses that are often exacerbated in these types of arrangements. It also overlooks the severe environmental impacts of industrial agriculture, and the unrealised potential of diversified agroecological systems to deliver a sustainable pathway to global food security.

The underlying problem is the concentration of power in food systems, which the report describes as a “lock-in of a different nature” that reinforces all of the other lock-ins. A small number of dominant agribusiness firms control the majority of chemical fertilizer supplies, pesticides and input-responsive seeds, for example, while power is highly concentrated at every node of the commercial food chain – in commodity export circuits, the global trade in grain, and through supermarkets and other large-scale retailers. These dominant actors are able to use their power to reinforce the prevailing dynamics that favour food systems geared to uniform crop commodities and massive export-oriented trade. Through lobbying policymakers, influencing research and development focuses, and even by co-opting alternatives - such as organic agriculture - these vested interests are able to perpetuate the self-reinforcing power imbalances in industrial food systems.

Resistance to change

Herein lies the crux of the issue for putting agroecology at the forefront of the global political agenda: the mismatch between its potential to improve food system outcomes, and its potential to generate profits for agribusiness:

“A wholesale transition to diversified agroecological food and farming systems does not hold obvious economic interest for the actors to whom power and influence have previously accrued. The alternative model requires fewer external inputs, most of which are locally and/or self-produced. Furthermore, in order to deliver the resilience so central to diversified systems, a wide variety of highly locally-adapted seeds is needed, alongside the ability to reproduce, share and access that base of genetic resources over time. This suggests a much-reduced role for input-responsive varieties of major cereal crops, and therefore few incentives for commercial providers of seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. The global trade and processing industry is also a major potential source of resistance to change, given that alternative models tend to favour local production and short value chains that reduce the number of intermediaries.”

Questioning whether the balance can be shifted in favour of diversified agroecological systems, the report goes on to identify several opportunities for change that are emerging through the cracks of the existing models of industrial agriculture. This includes the policy incentives enacted by some governments to shift their food systems towards more ecologically sustainable means of farming, such as the oft-cited example of Cuba that has been compelled to shift away from chemical input-intensive commodity monocropping since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Alongside the marked rise in public and academic awareness in favour of agroecology over recent years, as well as a surge in many grassroots schemes and initiatives that embody agroecological principles (i.e. farmers markets, community supported agriculture, direct sales shops and other new market relationships that bypass conventional retail circuits), also of note is the positive developments in the global governance agenda. There are now many examples of new intergovernmental processes and assessments that are responding to the case for a wholesale food systems transition.

In particular, the first International Symposium on Agroecology for Food Security and Nutrition was held in 2014, with a further symposium to be held in China in August this year, followed by a regional meeting in Hungary towards the end of 2016. In 2009, the findings of the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD) also gave the strongest support to the development of agroecological science and practice, presenting policymakers with an effective blueprint to confront today’s global food crisis.

But as the IPES-Food report concludes, these new opportunities are not developing nearly fast enough. Farming systems now stand at a crossroads, and there is a great danger that the current reinvestment in agriculture in the global South will replicate the pathways of industrialisation followed in wealthy countries. However, the author’s recommended “pathways of transition” are not overly inspiring given the convincing case for change presented in the earlier evidence sections of the report. There may also be nothing new for progressive scholars or food justice campaigners in the outline of new political priorities that must be urgently established by governments, no matter how important these policy shifts remain – such as the promotion of shorter supply chains and alternatives to mass retail outlets, and the ultimate relinquishing of all public support from monocultural production systems.

Redistributing power downwards

More compelling is the report’s acknowledgement that the distribution of power is crucial to the transition towards diversified agricultural systems. And hence the key to change is the establishment of new political priorities that can, over time, redistribute power in the global food system away from the dominant actors. That is, of course, an immense challenge that cannot succeed without the strengthening of social movements, from the many indigenous and community-based organisations that advocate for agroecological practices, to the diverse coalitions and civil society groups from the global North and South that embrace the food sovereignty paradigm. The fact that the report acknowledges the importance of these grassroots, bottom-up, farmer- and consumer-led initiatives makes it a potential tool for activists to use in the ongoing struggle for a just and sustainable food system.

From STWR’s perspective, the call for sharing is central to this alternative vision of a new paradigm in global agriculture that is designed in the interests of people and the environment, rather than the profit-making imperatives of multinational corporations. For example, as the historic Nyéléni Declaration on Agroecology asserts in its statement of common principles from February last year, collective rights and the sharing of access to the commons is a fundamental pillar of agroecology, which is as much a political movement as a science of sustainable farming. It is fundamentally about challenging and transforming structures of power in society, and placing the control of the food supply – the seeds, biodiversity, land and territories, waters, knowledge, culture and the commons – back into the hands of the peoples who feed the world, the vast majority of whom are small-scale producers.

If governments are to finally accept their responsibility to guarantee access to safe, nutritious food for all the world’s people, there is now a clearly established roadmap of the policies needed to democratise and localise food economies in line with the principles of sharing and cooperation. The IPES-Food report has provided another valuable assessment and set of recommendations that strengthens the case for a global transition towards food systems that diversify production and nurture the environment in holistic ways, rebuilding biodiversity and rehabilitating degraded land. The core of the challenge is not a lack of evidence, as the report authors have again made clear; it is the ideological support for an outmoded model of agriculture that continues to generate huge profits for the few, at the expense of long-term healthy agro-ecosystems and secure livelihoods.

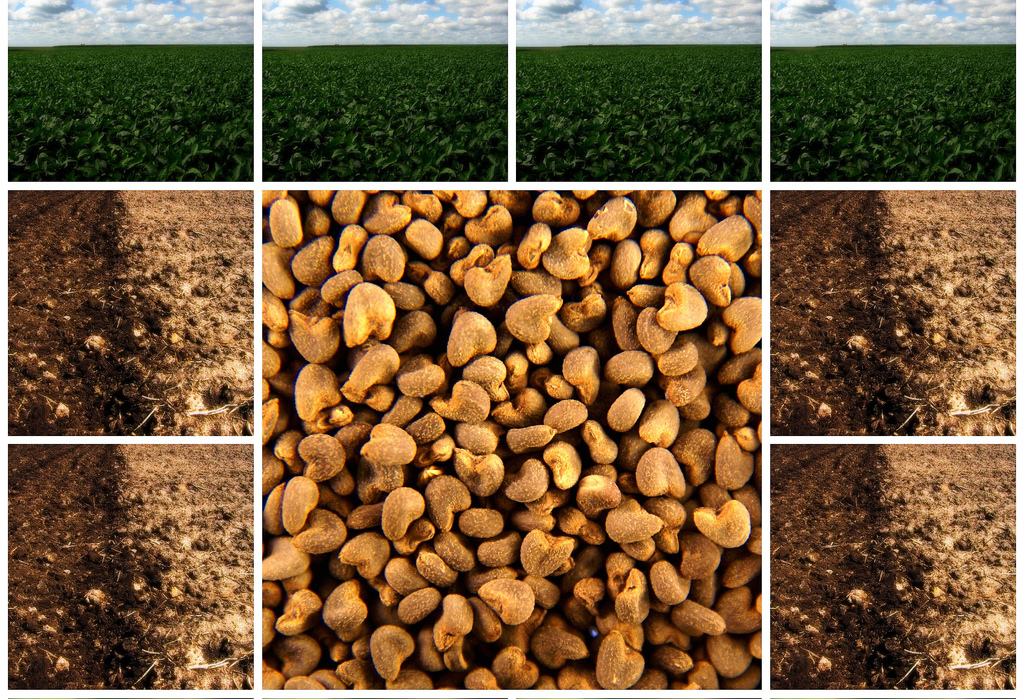

Photo credit: pawpaw67, flickr creative commons