To curb rising inequality, global leaders must work together to stop the flow of illicit wealth and mitigate tax avoidance, write John Irons & Xavier de Souza Briggs in the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

In many corners of the world, there is a growing belief that leaders, companies, and institutions are not accountable to the people they are supposed to serve. There is also powerful new evidence that our leaders are failing to address one problem at the heart of these corrosive trends: extreme and growing economic inequality. While there are straightforward ways the world’s leaders—inside and outside of government—could act together to enhance transparency and accountability, two big developments emphasize the daunting scale of the task at hand.

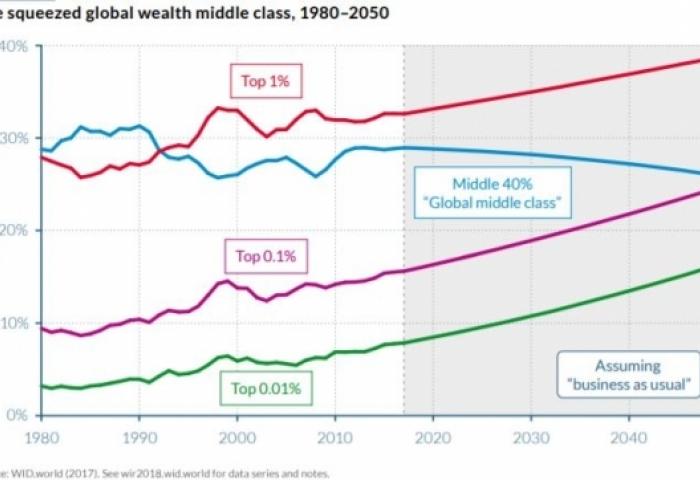

First, a monumental new report released late last year from the World Inequality Lab—unprecedented in its scope, and featuring the most complete body of global wealth and income data ever analyzed—underscores that the wealth gap is driven primarily by public policy choices and that the growth of that gap is accelerating. In the United States, the share of personal wealth now held by the top 1 percent has reached a sustained peak not seen since the Great Depression. Globally, if these trends continue, by 2050, the top tenth of 1 percent of humanity will possess as much wealth as the 40 percent considered middle class.

Second, sweeping federal tax reform passed in the United States will accelerate the growth of that wealth gap dramatically. In 2018, the top 1 percent of the population will receive an average tax cut of more than $50,000, while those in the bottom quintile will receive just $60 on average. By 2027, the top 1 percent will receive 83 percent of the total benefits. This is a massive transfer of public wealth into the bank accounts of those who have already benefited the most from recent economic growth.

What’s worse, the tax law has provisions that will also make it harder for other countries to promote transparency and run equitable tax systems that can help reduce inequality. For example, the United States has refused to adopt the Common Reporting Standard used by most wealthy nations to expose and mitigate cross-border tax evasion. This step backward comes in spite of the revelations in the Paradise Papers that spotlight the global network of offshore tax shelters that help the world’s wealthiest individuals and entities avoid domestic laws.

Of course, America’s new tax law is just the most recent and vivid demonstration that the growth of inequality is no accident. Technology, global trade, and other factors have contributed, to be sure. But the effects of decades of economic policymaking on inequality are well-documented in the World Inequality Lab report. Consider the fact that in 1980, Western Europe and the United States had roughly similar levels of wealth inequality. Since then, our paths diverged sharply, with inequality in the United States growing to levels not seen in 80 years and far eclipsing levels in Western Europe today. As the New York Times put it in its coverage of the report, “More aggressive redistribution through taxes and transfers has spared Europe from the acute disparities that Americans have grown used to." National policy choices of the past have built the world as it is today—and the choices we make now will determine its future.

It’s clear that, when presented with the opportunity to change course in the face of mounting inequality, policymakers decided instead to step on the gas and accelerate that widening divide. It’s difficult not to conclude, as one of the report’s authors Thomas Piketty recently noted to Quartz, that the latest US tax reform efforts will “exacerbate the trend towards rising inequality.”

Yet acknowledging this fact shouldn’t lead us to pessimism. Political leaders on both sides of the aisle in the United States have acknowledged the problem corporations and other entities shielding profits in overseas tax havens pose. It’s time policymakers take steps to ensure that wealthy individuals and corporations—those who benefit most—are held fully accountable under these new rules. We should build on existing law by enhancing cooperation with other nations to curb tax avoidance and secrecy.

We shouldn’t have any illusions about the obstacles facing action. Without a doubt, the current political moment is a challenging one. A surge in nationalism has led many countries to look inward and spurn global cooperation. Within nations, the prospects aren’t much better. Particularly in the United States, as government implements the new tax law, there seems to be little appetite for another change in course.

And yet, the implications of ongoing tax avoidance are massive, glaring, and unacceptable. Globally, tax avoidance represents at least $500 billion lost annually. The United States alone loses $189 billion or more each year. That’s money that should and could be going into vital needs, such as infrastructure, schools, health, and worker retraining.

Despite the challenges we face, it’s clear enough what we must do to curb the rise of inequality. Chiefly, global leaders with an interest in mitigating it must work together to expose the enormous and undocumented flows of illicit wealth—a problem that no nation can solve alone. For example, advocates across nations recommend creating a global financial register that documents and tracks the ownership and movement of financial assets—and real ownership of companies—worldwide. Adopting such standards would deal a major blow to corruption.

This kind of collaborative global approach is not unprecedented, and no period of political inaction is permanent. In 1978, for instance, Sweden became the first country in the world to ban aerosols, responding to research that showed that the accelerants degraded the planet’s ozone layer. In the decade that followed, more countries followed suit, until virtually all nations agreed to reduce ozone-depleting chemicals. Today, it’s clear that the ozone layer is in recovery—in large part because a first-mover nation helped spur global action.

Similarly, in the early crunch of the 2008 financial crisis, the world’s central banks worked together to prevent a global recession from becoming a depression. Actions included cutting interest rates, injecting liquidity into capital markets, allaying the damage of toxic assets, and stabilizing bond markets. The combined efforts of the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, Bank of Japan, and others reversed the course of a perilous economic moment. We know we can act collaboratively in moments of global crisis—the question becomes whether we can act collectively to avoid the next crisis.

At the very least, the World Inequality Report represents an important first step toward this goal. In recent years, we have seen powerful results when we make data and evidence accessible and analyze it, when journalists tell the story, and when citizens mobilize to make their voices heard and hold leaders accountable. The Panama Papers, which uncovered massive fraud and tax evasion across borders, is a clear example of the value of registries and what citizens can do when they have access to transparent information.

By curbing international tax avoidance, enhancing transparency, and promoting global standards that help ensure corporations and individuals pay their fair share, we can begin to curb the rise of inequality where it is doing the most harm. But more immediately, we can give people in democratic societies worldwide a reason to once again believe their institutions are working to serve them.

John Irons is the director of Future of Work at the Ford Foundation and was previously managing director of Global Markets at the Rockefeller Foundation.

Xavier de Souza Briggs is the vice president of Inclusive Economies and Markets at the Ford Foundation, and was previously a professor at MIT in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning.

Orignal source: Stanford Social Innovation Review

Image credit: WID World