The National Health Service in Britain was inspired by the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, both now marking their 70th birthday. We can look back at how unrestrained neoliberalism swallowed those dreams of the 20th century and co-opted socioeconomic rights along the way, writes Afua Hirsch.

I personally struggle a bit with anniversaries. Britain loves them, of course. A century of votes for some women (not all, a nuance that is often lost); the centenary of the end of the first world war, which should also be about Britain’s imperial solders, who were treated appallingly and then forgotten. To say I had mixed feelings when the government held a Windrush 70th anniversary celebration at 10 Downing Street last week is a bit of an understatement. Theresa May was clearly not going to let the denial of basic rights to hundreds of Windrush-generation Britons get in the way of having a good party.

This year is giving us a bumper crop of 1948 commemorations, but we forget how linked they are. The Empire Windrush ushered in a new age of mass migration from Britain’s empire and Commonwealth, and the multicultural nation we have today. The NHS was founded in 1948, an achievement regarded – the first patient recalled Nye Bevan having told her – as “the most civilised step any country had ever taken”.

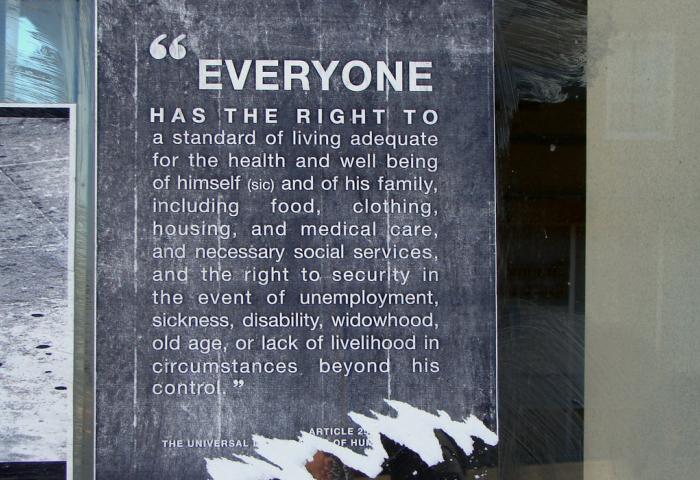

Its often-forgotten context was another milestone from 1948: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which also turns 70 this year, an anniversary far less likely to be celebrated by No 10 or any other branches of government when it arrives in December. Most of us know the basics of the rights it enshrined, such as the right to life or liberty or protection from torture. But how many of us are aware of the link with the NHS? Socioeconomic rights, guaranteeing a minimum level of welfare and access to resources, were a core part of the 1948 vision. Far from dismissing these as a nice idea, as we tend to now, Britain was making them a reality, with the radical creation of an institution that made healthcare free and universal.

All three of these 1948 anniversaries are linked. The human rights framework, with its attention to socioeconomic rights such as healthcare and housing, provided a language for the vision of fairness implicit in Britain’s postwar welfare state. The NHS was one of its key pillars. And mass migration, which began in earnest that year – at the British government’s invitation – has been intrinsically linked with its development.

Fast-forward to 2018, and human rights have become the kryptonite of the populist west. In Britain they represent, in the eyes of a significant faction of our ruling party and our media, a charter for undeserving minorities who are wrongly prioritised over hardworking Britons by an ultra-liberal, European, judicial elite. In Hungary they represent a threat to white, Christian, Hungarian culture, by protecting the asylum claims of people who are neither white, Christian nor Hungarian. In Donald Trump’s US, they represent the apparently repellent idea that immigrants should enjoy some kind of due process before facing deportation.

At the root of these suspicions is a sense of having been left behind: of wages being squeezed, or of finding access to schools, hospitals and housing newly scarce because of competition from migrants. This can be perception as much as actual experience. Hungary has taken the most dramatic counter-human rights steps against immigrants, despite having relatively few, just as those parts of Britain most worried about immigration have experienced the lowest amount of it.

It’s ironic because, were we to use anniversaries less selectively and for their intended purpose (reminding ourselves of what actually went before), we would know that the protection of human rights was meant to address such concerns. In 1948, socioeconomic rights meant access to a fair wage, good housing, healthcare and education for the masses, not just protection against violations for minorities. It was acknowledged then that freedom without the economic means to live a dignified life is no freedom at all.

The past is a foreign country. We wouldn’t dream of creating the NHS now if we were starting from scratch, in our present land of neoliberalism, suspicion towards foreigners and decaying social contracts. We would not have agreed to a declaration placing socioeconomic rights on an equal footing with political and civil rights. The only thing we would replicate – as we are doing – is the trawl round the former colonies, quietly recruiting people to fill gaps in the public sector, hoping British people wouldn’t notice.

Western nations are as reliant on immigration as ever but are less willing than ever to acknowledge this reality – a fact that a few glasses of Windrush-inspired bubbly at Downing Street does little to conceal. Instead they have fanned the flames of populism among disenfranchised voters who, ironically, would have benefited from the rights conferred 70 years ago, had they been implemented in the redistributive way in which they were conceived, but now are among their most vocal enemies.

This year is the 40th anniversary of another milestone, the Alma-Ata declaration. In 1978 the World Health Organization declared that primary healthcare should be freely available to everyone in the world by the year 2000. In hindsight, that seems so sweet. It required, these idealistic WHO members sensed, a shift from militarisation to peace, a redistribution of power from the global north to the global south, and a New International Economic Order (NIEO).

But it was right. The kind of equality people now yearn for would have required nothing less than a total reimagining of global financial systems, resource distribution and power. Instead, Alma-Ata was just another utopian vision quickly shelved as rising inflation, debt crises and recessions solidified neoliberalism in the global north and ushered in devastating structural adjustment policies in the south, making access to free universal healthcare a distant dream.

In this bumper year of anniversaries, we can look back at how that unrestrained neoliberalism swallowed the dreams of the 20th century and co-opted human rights along the way. And at how, in a coup for populist propaganda, the bogeyman that emerged in the 21st century was not this neoliberal order, but the rights it hijacked to such great effect.

And it’s why we will celebrate anything this year but the 70th birthday of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – even though it is, perhaps, the anniversary of all anniversaries to remember.

Afua Hirsch is a columnist for the Guardian.

Original source: The Guardian

Image credit: Richard Lemarchand, flickr creative commons