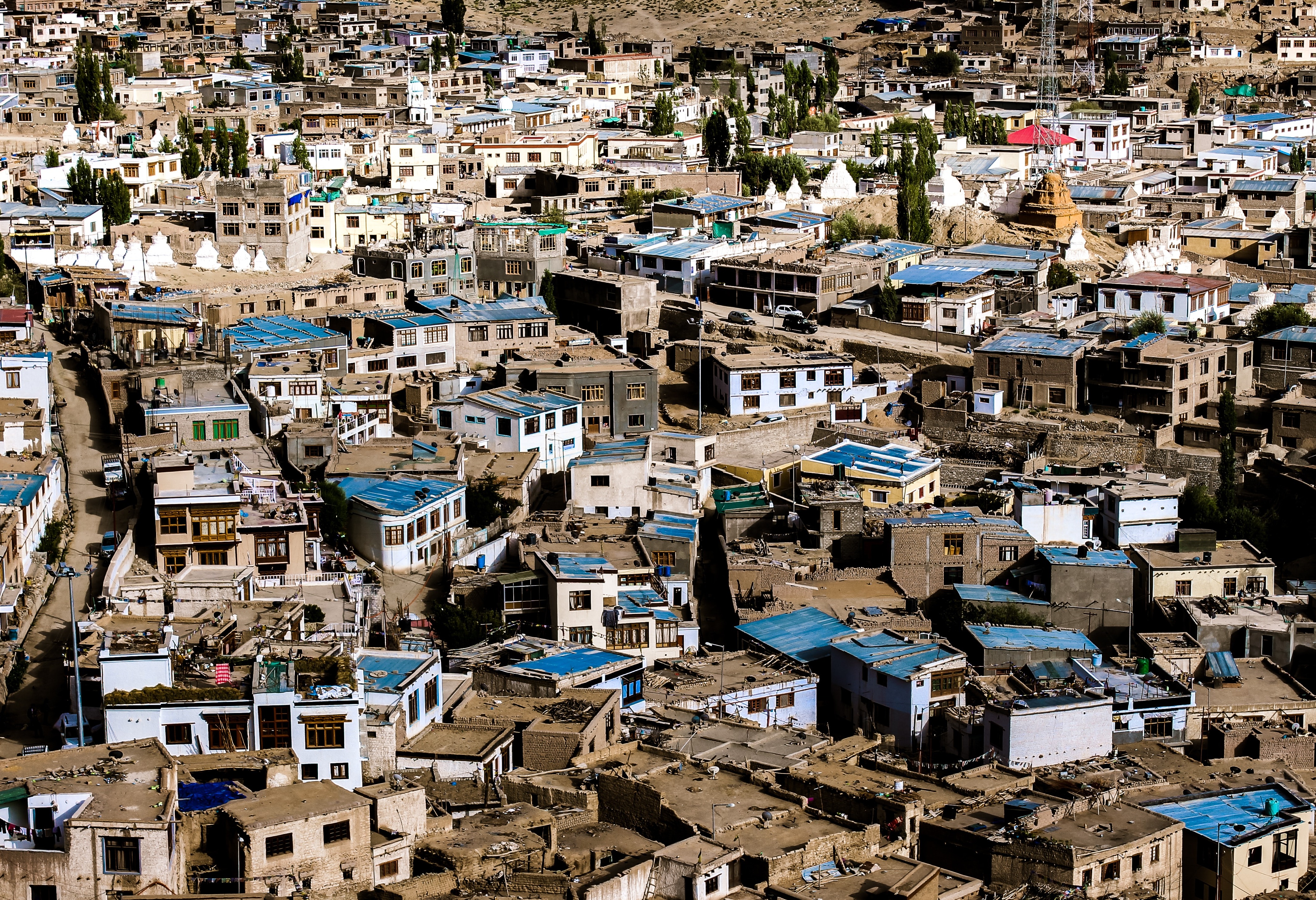

By 2050, nearly 70% of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas, making the proliferation of informal settlements inevitable – unless world governments take bold action, writes Jonathan Reckford and Joseph Muturi for IPS news.

When representatives from dozens of countries gathered recently at the UN High Level Political Forum in New York to share progress on their efforts to achieve the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), this disturbing reality was clear: the world is not even close to meeting the goals by 2030 as intended.

According to the report released at the meeting, progress on more than half of the SDG targets is weak and insufficient, with 30% of targets stalled or in reverse. In particular, progress towards SDG 11, which centers on making “cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” is stagnating, signaling regression for the third year in a row.

Unless governments take urgent action to address the plight of more than 1 billion people struggling daily to survive in slums and other poorly constructed informal settlements, we will not achieve the SDGs.

Access to affordable, safe housing is a fundamental human right, and intrinsically linked to building sustainable and resilient communities. It’s time world leaders turned their attention to improving housing conditions in informal settlements as a critical first step in helping to solve the most pressing development challenges of our time, from health and education to jobs and climate resilience.

Consider Milka Achieng, 31, who lives among the more than 250,000 residents of Kibera, a bustling hub of mud-walled homes and small businesses that make up one of the world’s largest informal settlements on the south side of Nairobi, Kenya.

Every day, Milka heads out for work and walks past the kiosk where she pumps water that isn’t clean enough to drink without boiling. She passes neighbors who live with the constant fear of eviction and the threat of deadly fires sparked by jerry-rigged electrical lines.

Yet despite these conditions, Milka remains upbeat. She works for a Kenya-based startup that, from its production facility in the heart of Kibera, cranks out firesafe blocks designed to make homes in informal settlements safer and more resilient. These are the kinds of innovative, scalable solutions that not only hold promise for the future of Kibera, but also for the millions of families struggling to keep their loved ones healthy and safe in informal communities around the globe.

By 2050, nearly 70% of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas, making the proliferation of informal settlements inevitable – unless world governments take bold, collective action.

A new report reveals the incredible, transformational benefits – in terms of health, education, and income – if world leaders invest in upgrading housing in informal settlements. The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) modeling from 102 low- and middle-income countries shows that if people living in informal settlements gained access to adequate housing, the average life span would jump 2.4 years on average globally, saving 730,000 lives each year.

This translates to more deaths prevented than if malaria were to be eliminated. The report also found that as many as 41.6 million additional children would be enrolled in school worldwide.

Economic growth, meanwhile, would jump by as much as 10.5% in some countries, whether measured as GDP or gross national income per capita. The resulting increase in living standards would exceed the projected cost of improving informal settlements in many countries.

These findings provide a long-overdue wake-up call to governments and municipal authorities that prioritizing safe and secure housing would have far-reaching implications for advancing not just community wellbeing, but national and global economic prosperity.

World leaders whose countries contribute billions of dollars annually to foreign assistance yet don’t prioritize improving informal settlements are making a grave mistake. Their goals related to education, health, and other areas of human wellbeing hinge on how well the world responds to trends such as growing inequities, rapid urbanization, and a worsening global housing crisis.

As the heads of an international housing organization and a global network of slum dwellers, respectively, we believe governments have an urgent responsibility to invest in comprehensive solutions to our global housing crisis.

This includes supporting start-ups, such as Milka’s factory, which are pioneering innovative, low-cost, and community-driven solutions to strengthen the foundation of unsafe housing settlements worldwide.

Simultaneously, officials at the global, national and municipals levels must ensure that residents have land tenure security, climate-resilient homes, and basic services such as clean water and sanitation.

Importantly, IIED researchers also concluded that, while they couldn’t put a precise number on it, the rehabilitation of informal settlements would have a clear and positive “spillover effect” by strengthening environmental, political and health care systems for all. This, in turn, would improve overall societal wellbeing for generations to come.

Upgrading the world’s supply of adequate housing is a lever for equitable human development and a cornerstone for sustainable urban development. Global, national and community stakeholders must join forces with the more than 1 billion voices clamoring for greater access to safe and secure homes.

When residents of informal settlements do better, everyone does better. Strikingly, it’s that simple.

Jonathan Reckford is president and CEO of Habitat for Humanity International. Joseph Muturi is chair of Slum Dwellers International.

Original source: Inter Press Service

Image credit: Varun Nambiar unsplash