Key points:

-

The burning of fossil fuels is the largest contributor to global warming, and it will be impossible to keep carbon emissions to safe levels if governments continue to subsidise fossil fuel production and consumption.

-

Subsidies provided to producers and consumers of fossil fuels worldwide currently amount to $509bn annually, compared to only $66bn in subsidies for renewable energy.

-

Biofuel subsidies currently amount to $22bn a year, even though evidence suggests that biofuels do not constitute an ethical, environmentally sustainable or economically viable alternative to fossil fuels.

-

Governments could raise $173bn in the immediate term by progressively reducing consumer subsidies and eliminating producer and biofuel subsidies altogether. This figure could cumulatively increase to $531bn a year if consumer subsidies are phased out completely by 2020.

-

International development banks, aid agencies and export credit agencies also provide significant financial support for controversial fossil fuel projects in developing countries - a trend that currently shows no sign of abating.

As greenhouse gas emissions continued to increase by a record amount last year, redirecting the enormous financial support given to the fossil fuel industry should constitute an urgent priority for world leaders.[1] The burning of fossil fuels is the largest contributor to global warming, and the International Energy Agency (IEA) recently reported that the continued building of fossil fuelled power stations over the next five years will make it impossible to keep carbon emissions to safe levels.[2] Ending damaging subsidies for highly polluting industries could enable governments to redirect resources to clean and renewable energy sources, as well as provide climate financing for adaption and mitigation programs in developing countries where climate change is already having a devastating impact.

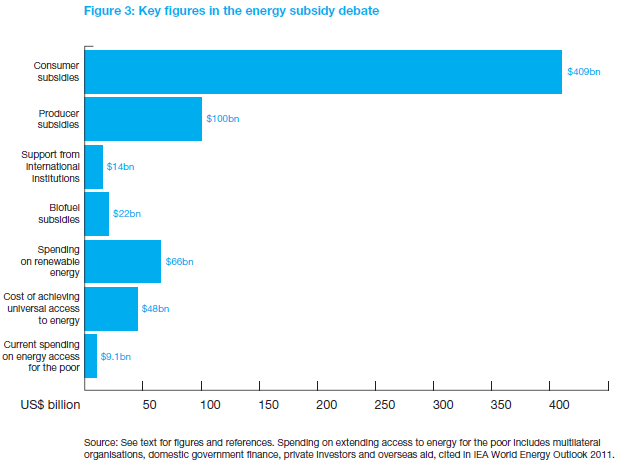

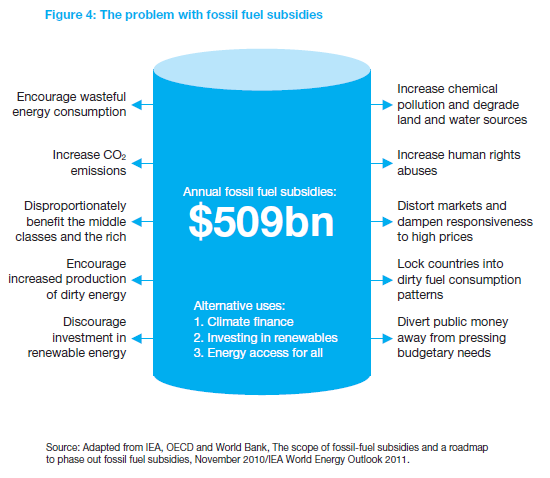

Fossil fuel subsidies from governments fall into two broad categories: ‘producer subsidies' that constitute financial transfers to the fossil fuel industry - mainly large oil and gas multinationals involved in extraction, processing and distribution; and ‘consumer subsidies' that are mainly provided to reduce the end-use prices of fossil fuels. While notoriously difficult to estimate, these two forms of fossil fuel subsidies alone currently amount to an estimated $509bn annually.[3] In comparison, rich nations collectively spend less than a third of this amount combating poverty through official development assistance [see section of this report on ODA], and support for renewable energy remains low in comparison to conventional fuels, at $66bn a year - around one third of which is given to biofuels despite their destructive impacts [see box].[4]

In economic terms, fossil fuel subsidies make alternative sources of renewable energy appear relatively more expensive, thereby reducing demand for them at a time when a switch to low carbon energy supplies is vitally important for meeting emission targets. As well as undermining the competitiveness of energy alternatives that are clean, green and economically viable, artificially lowering dirty energy prices can also exacerbate price fluctuations in energy markets.[5] The overall effect of maintaining subsidies is to lock economies into longer-term reliance on fossil fuels, and increase the economic advantage of these powerful and highly polluting industries at precisely the moment we urgently need to move away from their dominance in our economies. This trend is further exacerbated by the fact that few countries properly include the environmental costs of the fossil fuel cycle in the prices for those fuels.

Put simply, these subsidies encourage the overuse of carbon intensive energy and the depletion of fossil fuel deposits. And this is notwithstanding the wider impacts of ‘dirty energy' production, such as chemical pollution and the extensive degradation of land and water sources.[6] For example, the life cycle of coal generates a waste stream and carries multiple hazards for health and the environment that are external to the coal industry. These ‘externalities' are estimated to cost the U.S. public as much as $500bn or more each year. If these damages are accounted for in the price of coal it could triple the cost of coal-generated electricity, and therefore make non-fossil fuel power generation more economically competitive.[7]

Subsidies on fossil fuel consumption

Consumer subsidies account for the largest proportion of total government support, and jumped to $409bn in 2010 with the vast majority of them provided in developing countries.[8] This type of subsidy alone is expected to reach a record $630bn in 2012, according to the IEA's latest estimate.[9] Support for energy consumption can be provided through several channels, including direct financial transfers, tax relief, price controls intended to regulate the cost of energy to consumers, and schemes designed to provide consumers with rebates on purchases of energy products.[10] The defenders of consumer subsidies argue that they help to lower the cost of fuel and electricity for the poor, but most of the benefits typically go to the wealthy and those on middle-incomes who are more able to afford motor vehicles, connect to the electricity grid and own electricity goods.[11] In 2010, only 8% of the subsidies for fossil fuel consumption reached the poorest 20% of the population.[12]

As widely proposed by various international agencies, governments should gradually phase out inefficient consumer subsidies in developing countries that encourage wasteful consumption and discourage users from shifting to cleaner sources of energy.[13] However, ending consumer subsidies must be accompanied by targeted assistance and safety nets to ensure that the poor have access to modern energy services. There are a number of options available to governments for ensuring that the poor have access to fuel during a transition stage, such as temporarily maintaining fuel subsidies that target the poor and introducing other short-term measures to alleviate the impact of fuel price increases on poorer households.[14] The IEA estimate that it would cost only $48bn each year to ensure universal access to energy for the 2.7bn people who still rely on biomass for fuel and the 1.3bn people who live without electricity.[15]

Evaluations by the IEA suggest that phasing out just consumer subsidies universally by 2020 - although an ambitious objective - would decrease global primary energy demand by 5%, equivalent to the combined energy consumption of Japan, Korea and New Zealand. Global demand for oil would then reduce by the equivalent of around one quarter of current US consumption levels. As a result, global CO2 emissions would fall by nearly 6% in 2020.[16] According to another study by the OECD, removing consumption subsidies in the 20 largest developing countries over the next decade would reduce global CO2 emissions by at least 10% in 2050.[17]

Government support for fossil fuel production

Producer subsidies are more difficult to estimate and are mainly relevant to rich countries, although a survey by the Global Subsidies Initiative suggests that they could be as high as $100bn a year.[18] Most if not all of the G20 countries are believed to provide this form of support to the producers of fossil fuels, which can take many forms including: direct grants, preferential tax treatment, subsidised or guaranteed loans, and undercharging for the use of government-supplied goods or assets.[19] However, current estimates of producer subsidies are focused mostly on tax breaks, and coverage of credit and insurance subsidies, subsidised government ownership or oil security-related spending is more sparse. Producer subsidies in developing countries can also be very large, although these are rarely tracked at all.[20]

In contrast to consumer subsidies, government support for fossil fuel energy production cannot be justified on the basis of responding to social needs and distributional objectives. Moreover, producer subsidies protect fossil fuel companies that might not otherwise be competitive, at the expense of industries in related sectors such as renewable energy. The producers of fossil fuels, particularly oil, are among the most profitable and established industries in the world, yet the main benefits of tax breaks and other supports are generally passed on to shareholders in their companies. As such, the rapid phasing out of this enormous drain on government finances should be a major priority of reform efforts.

International support for the dirty fuels industry

International and regional financial institutions and export credit agencies are also key sources of financial support for the production of fossil fuels globally that are not included in these domestic subsidies figures. In particular, the World Bank Group and other regional development banks continue to be some of the largest supporters of environmentally harmful coal, oil and gas projects in developing countries - a trend that shows no sign of abating. For example, the World Bank provided a record-breaking $6.6bn in fossil fuel financing during 2010, an increase of 116% over the previous year. Of this total, lending for coal-based power reached $4.4bn, an increase of 356% over 2009.[21] The overall level of financial commitment to the fossil fuel industry from these various development institutions climbed from $11.7bn in 2008 to $14.4bn by 2010.[22] This significant level of financial support is not technically classified as a subsidy and is provided largely in the form of credit supports, including direct loans, loan guarantees, and various export insurance products (hence they are not included in the global fossil fuel subsidies estimate cited above). However, international credit supports ultimately act as subsidies by lowering the cost of building infrastructure for fossil fuel extraction and use in the developing world. All of this financing from international institutions could instead be an important source of public funds to help developing countries transition to cleaner energy and adapt to climate impacts.

The economic benefits of subsidy reform

As detailed in the breakdown below, it is technically possible for governments to raise an immediate sum of $173bn by gradually reducing consumer subsidies and eliminating producer and biofuel subsidies altogether. This figure could increase to around $531bn if governments complete the withdrawal of consumer subsidies by 2020, in line with the IEA's recommendation.[23] Such a massive sum of money is sufficient on its own to finance the poverty reduction and climate change mitigation initiatives outlined in this report, secure universal access to energy, as well as leverage a significant investment in renewable energy on a global scale.

A review of modelling and empirical studies by the Global Subsidies Initiative has estimated that reforming subsidies at a global level would result in significant economic gains, with aggregate increases in GDP in both OECD and non-OECD countries that could be as high as 0.7% per year.[24]Other major benefits of eliminating these subsidies include the huge amount of money that governments could save in costs associated with maintaining access to reliable fossil fuel supplies, such as the colossal military budget required to secure oil in foreign countries and safeguard its transportation to rich countries.[25] Most notably, the United States government has developed large stockpiles of oil over several decades and spent billions of dollars in defence costs to reduce the likelihood of supply interruptions and price shocks. These government costs act as an unofficial subsidy to oil and place an enormous burden on national resources paid for by the general taxpayer.[26]

While the IEA and other international organisations mainly justify the removal of subsidies as a means to correct ‘market distortions' in the energy sector, a far more pragmatic reason is simply to ensure that valuable public money can be put to better use. There is no sense in governments taxing carbon and committing to cut greenhouse gases on one hand, while continuing to subsidise the consumption and production of fossil fuels that lock us into unsustainable energy use on the other. Ending financial support for the fossil fuel industry would naturally reduce global carbon emissions, and must remain a key civil society demand as pressure mounts on governments to take much bolder action in the fight against climate change.

How much revenue could be mobilised

Producer subsidies: Removing the considerable financial support given to producers of fossil fuels in rich countries could save at least $100bn each year.[27]

Consumer subsidies: In line with the IEA's ambitious objective to completely phase out consumer subsidies by 2020, a gradual reduction of all consumer subsidies (which amounted to $409bn in 2010) could immediately raise an additional $51bn in developing countries. This figure could cumulatively increase by $51bn each year, until all consumer subsidies are eliminated entirely by 2020 [see note].[28]

Biofuel subsidies: Ending support for biofuels could raise a further $22bn annually [see box].[29]

Total potential revenue: $173bn in the first year,[30] increasing significantly each year thereafter to reach $531bn annually by 2020 if all producer, consumer and biofuel subsidies are eliminated.

Ending support for dirty energy

Abolishing fossil fuel subsidies already has considerable support amongst the international community. Since its adoption in 1997, the Kyoto Protocol included the lowering of fossil fuel subsidies as one of the measures that countries could undertake to limit CO2 emissions.[31] Commitments to begin these measures were taken at the Group of Twenty (G20) summit in Pittsburgh in 2009, and again in Toronto in 2010. For the first time, world leaders committed to "rationalize and phase out over the medium term inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption".[32]

The pledge also reached out beyond membership of the G20 with an almost identical commitment being undertaken by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in November 2009, extending fossil-fuel subsidy reform to an additional 12 countries.[33] A further group of countries led by New Zealand and including Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland also formed the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform group which aims at ensuring an ambitious and transparent outcome to the G20 process.[34] More recently, a High-Level Panel on Global Sustainability (including current or former heads of state or ministers) urged governments to phase out fossil fuel subsidies completely by 2020. Recognising that such decisions can be politically unpopular, as underlined by the unrest in Nigeria over fuel subsidy reductions at the beginning of 2012, the report emphasised that reducing fossil fuels subsidies must be done in a manner that protects the poor.[35]

In the context of an economic crisis, high and volatile energy prices, increasing concern over energy security and ongoing pressure to reduce carbon emissions there is also considerable cross-party political support for subsidy reform. Barack Obama specifically campaigned on the issue in 2008, and many high-profile figures have spoken out against using public funds to subsidise ‘dirty energy', including UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, Sir Nicholas Stern, Al Gore and even John Browne (former Chief Executive of BP).

Despite this wide-ranging consensus that unites environmentalists, economists and policymakers, the various pledges have yet to be translated into actual subsidy reductions. The G20 commitment was a positive step forward, but no country has yet initiated a subsidy reform programme specifically in response to the G20 pledge.[36] In fact, governments are expected to spend significantly more money subsidising fossil fuels in 2012 than they have in previous years.[37] There are also concerns surrounding the reporting of fossil fuel subsidies which remain spotty for many G20 member countries, while spurious reasons are given for omitting many subsidies from reform efforts and even from reporting. According to the latest review of progress, G20 nations are changing their definitions of what is an ‘inefficient subsidy' in order to prevent making changes to their actual subsidy policies, while non-reporting of subsidies is growing.[38]

The politics of subsidy removal

Internationally, the politics of implementing the G20's commitment to phase out support for fossil fuels poses a number of problems. While the dominant type of subsidies in industrialised countries are production subsidies, consumption subsidies mainly apply to developing countries. These poorer countries are legitimately concerned about access to energy for their populations, and may be unlikely to agree to significant subsidy reductions in international negotiations unless the developed nations offer some concessions and put additional finance on the table. Campaigners therefore see part of the solution as using savings from ending fossil fuel subsidies in rich countries to provide funding for climate finance, clean energy technologies and the alleviation of energy poverty in the South.[39]

A phased removal of subsidies, differentiated in time and by country income level, could also establish trust between countries and help build momentum towards the significant global reductions needed. For example, developed countries could commit to phasing out energy subsidies completely within five years; middle-income developing countries could aim for 10 years; and low-income countries could aim to halve subsidies within 10 years and completely eliminate them in 15 years.[40] However, limited data availability on government support for fossil fuels remains a significant hurdle to reform efforts, with even developed countries like Germany currently having gaps in information.[41]

Given the extremely slow pace of reform, civil society groups are now increasing the pressure on world leaders to fulfil their pledges and establish a definite plan to phase out fossil fuel subsidies by 2015. A large coalition of civil society groups has proposed a range of concrete measures to facilitate this process including: greater transparency and consistency in subsidy reporting; assistance and safeguards for developing countries and vulnerable groups; and identifying or establishing an international body to address the complexities involved in the phasing-out process.[42]

Subsidy reform has further implications for international development banks, bilateral aid agencies and export credit agencies that should end investments in fossil fuel extraction and use, while shifting the portfolio of their investments to focus on decentralised and sustainable energy solutions that meet the energy needs of the poor.[43] While some international aid agencies and even some export credit agencies have begun to shift investments towards energy production options that are both cleaner and more effectively targeting the poor, the main trend is still towards large-scale fossil fuel development.[44] This is particularly the case for the World Bank Group. The Bank remained the focus of several worldwide campaigns and large demonstrations in 2011 demanding an end to its controversial fossil fuel lending in developing countries[45] - including mass opposition to the Medupi coal plant in South Africa, now set to be the world's seventh largest coal-fired power plant at a cost of over $3bn.[46]

Battling the fossil fuel lobby

It is widely agreed that there are no major administrative hurdles to eliminating tax breaks, subsidies and other supports to the fossil fuel industry. Removing domestic production subsidies is estimated to have very little impact on global oil supply, or on either global or domestic oil prices. Even exploration and production costs would increase by but a tiny percentage.

Yet there remains a long history of influence that fossil fuel companies wield over governments. In the US, oil and gas companies are always among the industries to spend the most on lobbying, pouring $132.2m into these efforts in 2008 alone.[47] Barack Obama notoriously received more money from the fossil fuel industry than any other lawmaker except his Republican opponent during the 2008 election campaign. Current members of Congress took over $25m in campaign contributions from oil, gas and coal companies in 2009-2010, some of which was paid to House members voting on ending subsidies under the Energy Tax Prevention Act of 2011.[48] According to the pressure group Oil Change International, U.S. fossil fuel companies are currently getting $59 in subsidies for each $1 they donate to election campaigns - an incredible 580% return.[49] This lobbying pressure from the fossil fuel industry may be even stronger in countries where the state is heavily involved in the fossil fuel sector, such as Iran, Mexico, Venezuela or Russia.

Clearly the greatest barriers to ending fossil fuel subsidies are political, not technical, and these barriers are largely driven by the dirty energy industry itself. As a result, many environmental activists are now focusing their efforts on pressuring governments to phase out fossil subsidies as a giant step towards solving the climate crisis, with many actions taken at the Rio ‘Earth Summit' in June 2012.[50]While governments scramble to make billions of dollars worth of cuts to national budgets, there could not be a tighter case for ending corporate welfare to oil, gas and coal companies and rejecting all their campaign contributions. Campaigners point out that this requires a separation of the fossil fuel industry from the state in order to end its political influence over decision-makers, and to ensure that the current system of energy subsidies reflects the public interest and not the special interests of ‘Big Oil' and its wealthy allies.

Box 10: Why we should stop subsidising biofuels

In the 30 years since ‘gasohol' first entered the marketplace in the US, government subsidies for biofuel production have grown considerably in scope and size. Unlike fossilised fuels that make up oil and coal, biofuels are made from living plants such as rapeseed, palm oil, soy, sugar cane or jatropha - although production of these crops often requires significant inputs of fossil fuels as well. Biofuel subsidies may pale in comparison with the vast sums of money spent in rich countries to support their fossil fuel or agricultural sectors, but the financial costs to taxpayers are still sobering.

Global support for biofuels has rapidly expanded over the last decade and reached $22bn in 2010, the bulk of it in the US and EU.[51] Although biofuel production came to an abrupt halt in 2010 as a result of poor margins in the US and Brazil,[52] the biofuel industry is still set to grow significantly in the years ahead if existing targets set by governments are maintained. For example, a mandate in the US requires that 36bn gallons of biofuels must be blended into the US fuel supply by 2022, which would lead to a six-fold increase in subsidies compared to 2008.[53] The EU's Renewable Energy Directive (RED) also commits Member States to a target whereby 10% of all land transport fuels should come from renewable sources by 2020, the vast majority of which is expected to be met from biofuels.[54]

The myths of ‘agrofuels'

Politicians and corporations justify the large-scale production of biofuels on the basis that they can reduce carbon emissions and lessen our dependency on conventional mineral oil. In reality, however, a wealth of studies have warned that biofuels can produce more greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than the fossil fuels they are meant to replace when accounting for the land that must be cleared and planted elsewhere to make up for the loss of food crops.[55] Other evidence suggests that biofuels do not offer a safe or cost-effective way of improving fuel security. Even if all the carbohydrates in the world were converted to biofuel, it would still only provide enough fuel to replace 40% of global petrol consumption.[56]

Crops that may appear sustainable when planted on a small scale quickly turn into environmental problems as acreage grows to meet fuel demand. The rapid conversion of arable land to biofuel production also has serious implications for the environment, food security and the economy. The expansion of land used to grow biofuel crops like soy and palm oil is a major driver of deforestation in South America and South East Asia, threatening many species with extinction. Deforestation and land use change is already the cause of about one quarter of total global CO2 emissions.[57] Reports are also growing of forced evictions, appropriation of land and other violations of human rights in biofuel plantations in different parts of the developing world.[58]

Furthermore, the use of crops for fuels means there is less land available for growing food, which raises a serious ethical issue: the competition for grain between the world's 800 million motorists who want to maintain mobility, and its 2bn small farmers struggling simply to survive in developing countries.[59] In the wake of the global food crisis, many different studies show that a high percentage of the food price rise experienced in 2008 (possibly as high as 75% according to a leaked World Bank report)[60] was due to increasing demand for biofuels. If all countries were to meet their biofuel targets, tens of millions more people in developing countries could be driven into hunger.

An unlikely alliance

With such damning evidence, and at such an enormous cost, why do governments continue to subsidise the biofuel industry? A large part of the answer lies in the familiar capture of policymaking by well-organised special interests. An unlikely alliance has evolved around the biofuel boom which includes oil companies, agribusiness, farmers' unions, energy companies, venture capitalists, car manufacturers and even the biotech industry.[61] This powerful, self-interested lobby is able to influence government decisions and exploit loopholes surrounding regulation in order to increase the mandate for uneconomic biofuels. This may help explain why, in the US alone, there are more than 200 different kinds of subsidies to biofuels nationwide.[62]

There are signs that some governments and policymakers have listened to campaigners and are beginning to rethink their biofuel directives. In January 2008, the German government ended its tax exemptions and subsidies for biofuels,[63] and a recent report by 10 agencies including the World Bank and United Nations has called on G20 governments to eliminate biofuel subsidies due to the evidence that they increase volatility in global food prices.[64] At the end of 2011, campaigners also won a multi-year campaign in the US when Congress ended a corn ethanol subsidy worth around $6bn each year, as well as a tariff that helped encourage the development of biofuels.[65] Yet the worldwide trend still continues towards biofuel expansion, despite its destructive impacts and the misguided belief that it constitutes a viable alternative to oil dependency.

The message for governments should be clear and simple: dismantle all support measures for biofuel programmes (which includes blending and consumption mandates, tax breaks and import tariffs as well as public subsidies) and redirect efforts towards cutting demand, more efficient use of energy, and truly renewable energy sources. Limits, not incentives, must immediately be placed on the biofuels industry. In the words of food security analyst Eric Holt-Giménez: "The question is not whether ethanol and bio-diesel per se have a place in our future, but whether or not we allow a handful of global corporations to determine our future by dragging us down the dead end of the agro-fuels transition."[66]

Learn more and get involved:

Bank Information Centre (BIC): An organisation that influences the World Bank and other international financial institutions to promote social and economic justice and ecological sustainability. <www.bicusa.org/en>

Biofuelwatch: Campaigning against industrial bioenergy - energy linked to industrial agriculture and industrial forestry that includes ‘agrofuels'. <www.biofuelwatch.org.uk>

Beyond Coal: A grassroots campaign to end the massive effort to build new coal plants across North America. <www.beyondcoal.org>

Dirty Energy Money: A campaign to end US government handouts to oil, gas and coal companies and reject campaign contributions from these Dirty Energy industries. <dirtyenergymoney.com>

Earth Track: Founded in 1999 by Doug Koplow to more effectively integrate information on energy subsidies, Earth Track works to make government subsidies that harm the environment easier to see, value, and eliminate. <www.earthtrack.net>

#ENDFOSSILFUELSUBSIDIES: The online petition by campaign group 350.org to end all subsidies and handouts to the fossil fuel industry, and use that money to help build the green economy instead. <endfossilfuelsubsidies.org>

Greenpeace International: Front-line activism to expose the true costs of extracting and producing fossil fuels worldwide. <www.greenpeace.org/international/en>

Low Hanging Fruit: A key report on fossil fuel subsidies, climate finance and sustainable development, published by Oil Change International for the Heinrich Böll Stiftung, June 2012. <www.boell.org>

Oil Change International: An international campaign to expose the true costs of fossil fuels and facilitate the coming transition towards clean energy. <www.priceofoil.org>

Shift the Subsidies: An interactive database to visually track and analyse the flow of energy subsidies from international, regional and bilateral public financial institutions around the world. <www.shiftthesubsidies.org>

The Ultimate Roller Coaster Ride - An Abbreviated History of Fossil Fuels: Presented by the Post Carbon Institute and narrated by Richard Heinberg, this is a quirky five-minute synopsis of the unsustainable trajectory of fossil-fuel dependent economies. <www.postcarbon.org>

Notes:

[1] Fiona Harvey, ‘Worst ever carbon emissions leave climate on the brink', Guardian, 29th May 2011.

[2] International Energy Agency, ‘The world is locking itself into an unsustainable energy future which would have far-reaching consequences, IEA warns in its latest World Energy Outlook', Press release, 9th November 2011.

[3] See text below for figures; consumer subsidies estimated at $409bn a year, producer subsidies estimated at $100bn.

[4] International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2011, London: November 2011.

[5] International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2010: Factsheet, How big are the potential gains from getting rid of fossil-fuel subsidies?, 2010, <www.worldenergyoutlook.org/media/weowebsite/factsheets/factsheets-1.pdf>

[6] Paul R. Epstein and Jesse Selber (eds), Oil: A Life Cycle Analysis of its Health And Environmental Impacts, The Center for Health and the Global Environment Harvard Medical School, March 2002.

[7] Paul R. Epstein et al, Full cost accounting for the life cycle of coal, Ecological Economics Reviews, New York Academy of Sciences, 2011.

[8] IEA, World Energy Outlook 2011, op cit. Note: The annual level of subsidy fluctuates widely in response to international energy prices. In 2008, for example, consumer subsidies reached $558bn globally, compared to $312 in 2009.

[9] Estimate made by Fatih Birol, Chief Economist at the IEA, and included on the IEA website, <www.iea.org/weo/quotes.asp>

[10] Jehan Sauvage and Jagoda Sumicks et al, Inventory of estimated budgetary support and tax expenditures for fossil fuels, OECD, October 2011.

[11] The Global Subsidies Initiative, Achieving the G-20 Call to Phase Out Subsidies to Fossil Fuels, Policy Brief, October 2009.

[12] International Energy Agency (IEA), World Energy Outlook 2011: Executive Summary, November 2011, p. 7.

[13] IEA, OPEC, OECD, World Bank joint report, ‘Analysis of the Scope of Energy Subsidies and Suggestions for the G-20 Initiative', Prepared for submission to the G-20 Summit Meeting Toronto (Canada), 16 June 2010, pp. 8-9.

[14] IEA, OPEC, OECD, World Bank joint report, op cit, pp. 5, 39-41.

[15] World Energy Outlook 2011, op cit, p. 7.

[16] IEA, World Energy Outlook 2010: Executive Summary, November 2010, p. 14.

[17] Jean-Marc Burniaux et al, The economics of climate change mitigation: How to build the necessary global action in a cost-effective manner, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 701, 2009.

[18] The Global Subsidies Initiative, op cit.

[19] Jehan Sauvage and Jagoda Sumicks et al, Inventory of estimated budgetary support and tax expenditures for fossil fuels, OECD, October 2011.

[20] Doug Koplow et al, Mapping the Characteristics of Producer Subsidies: A review of pilot country studies, Global Subsidies Initiative, August 2010.

[21] Heike Mainhardt-Gibbs, ‘World Bank Group Energy Sector Financing Update', Bank Information Center, November 2010.

[22] Oil Change International, Shift the Subsidies Database, Institutions, <www.shiftthesubsidies.org/institutions>

[23] See note to calculation in possible revenue section below.

[24] International Institute for Sustainable Development, Untold Billions: Fossil-Fuel Subsidies, Their Impacts and the Path to Reform: A Summary of Key Findings, The Global Subsidies Initiative, April 2010, p. 11.

[25] Oil Change International, The Price of Oil, War & Terror, <priceofoil.org/thepriceofoil/war-terror>

[26] Douglas Koplow and Aaron Martin, Fuelling Global Warming: Federal Subsidies to Oil in the United States, 30th June 1998, chapter 4.

[27] The Global Subsidies Initiative, Achieving the G-20 Call to Phase Out Subsidies to Fossil Fuels, Policy Brief, October 2009.

[28] Note on calculation: Assuming an average of $409bn annually is spent on consumer subsidies, as per current estimates, then a gradual phasing out of these subsidies by 2020 would reduce this amount by $51bn over 8 years. This means that $51bn would be saved in 2012, $102bn in 2013, $153bn in 2014, etc., until $409bn is saved in 2020.

[29] IEA, World Energy Outlook 2011, London: November 2011, p. 508.

[30] $173bn = $100bn (producer subsidies) + $51bn (immediate reduction in consumer subsidies, see reference above) + $22bn (biofuels).

[31] Specifically, Article 2.1 of the Kyoto Protocol requires Annex I countries to implement "policies and measures" to achieve their emission limitation and reduction commitments, one of which includes the progressive reduction or phasing out of subsidies in all greenhouse gas emitting sectors. See Doug Koplow and Steve Kretzmann, ‘G20 Fossil-Fuel Subsidy Phase Out: A review of current gaps and needed changes to achieve success,' Oil Change International and Earth Track, November 2010, p. 16-17.

[32] The G20 Toronto Summit Declaration, University of Toronto, 27th June 2010.

[33] 2009 Leaders' Declaration, Singapore Declaration - Sustaining Growth, Connecting the Region, Singapore, 14th-15th November 2009.

[34] Subsidy Watch, The Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform: Supporting the G-20 and APEC commitments, Issue 42, February 2011, <www.iisd.org/gsi/subsidy-watch-archive>

[35] The High-level Panel on Global Sustainability, Resilient People, Resilient Planet: A Future Worth Choosing, Addis Ababa: January 2012, pp. 52-53.

[36] Doug Koplow, Phasing Out Fossil-Fuel Subsidies in the G20: A Progress Update, Oil Change and Earth Track, June 2012; Doug Koplow and Steve Kretzmann, G20 Fossil-Fuel Subsidy Phase Out, op cit.

[37] Natural Resources Defense Council, Governments Should Phase Out Fossil Fuel Subsidies or Risk Lower Economic Growth, Delayed Investment in Clean Energy and Unnecessary Climate Change Pollution, June 2012; Oil Change International, ‘No time to waste; the urgent need for transparency in fossil fuel subsidies', May 2012.

[38] Doug Koplow, Phasing Out Fossil-Fuel Subsidies in the G20, op cit.

[39] Oil Change International, ‘Shifting Fossil Fuel Subsidies to Provide Energy Access and Climate Finance', March 2010; Oil Change International, ‘Shifting Fossil Fuel Subsidies to International Climate Finance', June 2010.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Doug Koplow et al, Mapping the Characteristics of Producer Subsidies: A review of pilot country studies, Global Subsidies Initiative, August 2010.

[42] Oil Change International, ‘No Time to Waste', op cit.

[43] Oil Change International, ‘Shifting Fossil Fuel Subsidies', op cit.

[44] Oil Change International, Shift the Subsidies Database, Guide, <www.shiftthesubsidies.org/guide>

[45] For example, see: Bank Information Centre, ‘International Day of Action demands World Bank end fossil fuel funding', 1st March 2011.

[46] World Bank, Eskom Investment Support Project, South Africa, Overview: Project-At-A-Glance, accessed December 2011, <www.worldbank.org/projects>

[47] Aaron Kiersh and Dave Levinthal, Oil & Gas: Background, June 2010, <www.opensecrets.org>

[48] Dirty Energy Money Campaign, Key Findings: U.S. Congress: Awash with Dirty Energy Money, Updated 15th April 2011, <www.dirtyenergymoney.com>

[49] Steve Kretzmann, ‘One Dollar In, Fifty-Nine Out', Oil Change International, 26th January 2012.

[50] For example, see the #EndFossilFuelSubsidies campaign by 350.org, and the 'Stop governments propping up dirty energy' campaign by Friends of the Earth.

[51] IEA, World Energy Outlook 2011, London: November 2011, p. 508.

[52] Javier Blas, ‘Biofuels expansion stalls on output drop', Financial Times, 9th January 2012.

[53] Doug Koplow, A Boon to Bad Biofuels: Federal Tax Credits and Mandates Underwrite Environmental Damage at Taxpayer Expense, Friends of the Earth (USA), April 2009.

[54] Almuth Ernsting, Biomass and Biofuels in the Renewable Energy Directive, Biofuelwatch.org, January 2009, <http://www.biofuelwatch.org.uk/docs/RenewableEnergyDirective.pdf>

[55] For example, see The Gallagher Review of the indirect effects of biofuels production, July 2008, commissioned by the UK government. A study by the Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) also calculated that EU biofuel targets for 2020 would lead to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions of as much as 56 million tonnes of extra CO2 per year, the equivalent of putting an extra 26 million cars on Europe's roads by 2020. See Friends of the Earth, RSPB and ActionAid, Biofuels in 2011: A briefing on the current state of biofuel policy in the UK and ways forward, 2011, p. 3.

[56] Oxfam International, Another Inconvenient Truth How biofuel policies are deepening poverty and accelerating climate change, Oxfam briefing paper, June 2008, p. 14.

[57] Campaign Against Climate Change, Biofuels and climate change: the facts, accessed October 2011, <www.campaigncc.org/biofuelfacts>

[58] Asbjørn Eide, The Right to Food and the Impact of Liquid Biofuels (Agrofuels), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome: 2008.

[59] Lester R. Brown, Plan B 4.0: Mobilizing to save civilization, Chapter 1. Selling our future: food -the weak link, Earth Policy Institute, 2009.

[60] Aditya Chakrabortty, ‘Secret report: biofuel caused food crisis. Internal World Bank study delivers blow to plant energy drive', The Guardian, 3rd July 2008.

[61] Car manufacturers back a low carbon solution that does not force them to make major changes to the industry, while the biotech industry backs the genetic modification of crops to make them more suitable for biofuel production. See Campaign Against Climate Change, Biofuels and climate change: the facts, accessed October 2011, <www.campaigncc.org/biofuelfacts>

[62] Doug Koplow, Biofuels - At What Cost? Government support for ethanol and biodiesel in the United States, Geneva: Global Subsidies Initiative, October 2006.

[63] Julio Godoy, ‘German Biodiesel Forced to Compete', Inter Press Service, Berlin, 29th December 2007.

[64] Joshua Chaffin, ‘Report urges end to G20 biofuel subsidies', Financial Times, 9th June 2011.

[65] Friends of the Earth, ‘Six billion dollar subsidy for dirty corn ethanol defeated', News release, 23rd December 2011.

[66] Eric Holt-Giménez, Biofuels: Myths of the Agro-fuels Transition, Food First Backgrounder, Institute for Food and Development Policy, Summer 2007, Vol 13 No. 2.

Image credit: SorbyRock, flickr creative commons