Key points:

-

Strengthening tax systems in countries around the world remains the most pragmatic way for nations to share their financial resources more equitably and protect the poor and vulnerable.

-

A global super-rich elite currently hold up to $32tn of untaxed private wealth in tax havens, almost a third of which is amassed by developing countries.

-

This excessive leakage of revenues could be significantly reduced through the implementation of more effective international regulations for cooperation, transparency and accountability on tax issues.

-

As a minimum step toward ending all forms of global tax avoidance, clamping down on tax havens and preventing corporate trade mispricing could raise more than $349bn globally each year.

-

Preventing illegal tax evasion, strengthening tax systems in the Global South and adopting more progressive taxation policies in rich countries could raise billions more dollars of government revenue each year.

As harsh policies of economic austerity impact on employment opportunities, public services and poverty across the world, the call for a fairer redistribution of wealth and income is fast becoming the mantra for those seeking economic justice. Taxation - particularly on profits, bank interest and wages - is an essential prerequisite for ensuring a fair distribution of financial resources within a nation and reinforcing the sharing economy. In a period when inequality and financial insecurity continues to grow on a global scale, the prevention of tax avoidance by wealthy individuals and corporations must constitute an urgent priority for governments in both industrialised and developing nations.

On average, 37% of government revenue in rich countries comes from taxes levied on the wealth and income of individuals and businesses.[i] The level and type of taxation applied and the subsequent redistribution of these revenues largely determines how effectively a government is able to safeguard the basic needs of its citizens, reduce inequality and meet its broader international development commitments.

Analysts have long considered strengthening tax systems in the Global South as the preferred way of financing poverty reduction. ActionAid has calculated that developing countries could raise an additional $198bn each year by ensuring that 15% of government revenues come from taxes.[ii] Increasing national tax incomes has also become a key point of debate across Europe and the United States in recent years, as gaping holes in public finances and the widespread implementation of austerity measures has renewed public interest in ‘tax justice'.

Tax avoidance by wealthy individuals and multinational corporations - legitimised by national and international tax rules, and facilitated by a global network of highly secretive tax havens - means governments often fail to benefit from this much needed source of public revenue. According to new ground-breaking research into financial assets held offshore, it is conservatively estimated that governments are losing tax revenues of $189bn per year as a consequence of funds being invested in tax havens by 10 million individuals around the world.[iii] Oxfam has estimated that developing countries alone could be losing up to $124bn annually owing to the use of tax havens by the super-rich.[iv] During the last decade, tax havens helped facilitate the illicit flow of an estimated $6.5tn out of wealthy countries, the majority of which occurred through the manipulation of profits and costs by multinational corporations, a practice known as trade mispricing [see box 12 below].[v]

The global tax consensus

This massive loss of income is exacerbated by a global ‘tax consensus' widely promoted by multilateral agencies such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank over recent decades. In the global competition to attract foreign direct investment, governments are pressured to offer low tax rates and incentives to multinational corporations (MNCs). This creates a ‘race to the bottom' in which MNCs are able to play governments off each other in order to secure the biggest tax breaks, in return for the questionable benefits of increased productive investment in the host country [see box 12].

As a result of driving down corporate tax rates, governments in both the North and South have failed to ensure that high-income earners and large corporations contribute more to the public purse than ordinary tax payers on lower incomes. This is of particular concern in developing countries where the downward pressure on corporate tax revenues is generally more marked than in developed countries.[vi] Since developing countries tend to rely more heavily on tax revenues to finance essential welfare services, the impact of international tax competition can seriously impede their domestic sources of financing - especially when combined with reductions in custom revenues as a consequence of free trade agreements [see section 10 on import tariffs].

Corporate tax avoidance is big business and CEO rewards for facilitating it are still on the rise. A recent study found that 280 of the most profitable corporations in the US avoided a staggering $223bn in federal taxes over a period of three years, with more than half of this total ‘tax subsidy' going to just 25 companies.[vii] Another report found that 25 major US corporations paid more compensation to their CEOs than they paid in federal taxes, and five of these had a total of 267 subsidiaries registered in tax havens. On average, the remuneration for CEOs of major US corporations was 325 times the typical income of American workers.[viii] Similarly, only a quarter of French multinational corporations, and a third of those based in the UK, paid tax in their respective countries.[ix]

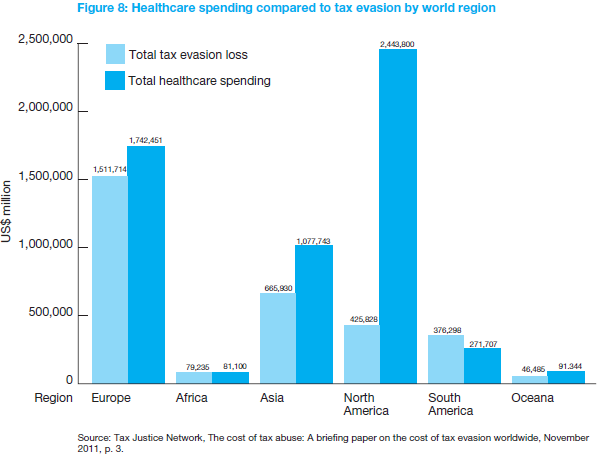

Unlike tax avoidance activities which legally exploit tax loopholes, tax evasion activities involve the illegal non-payment or under-payment of taxes and are subject to criminal or civil legal penalties. Research published by the Tax Justice Network examined the prevalence of ‘shadow economies' around the world where economic activity takes place illegally without taxation, including through the use of tax havens. The report found that if governments ended tax evasion globally, an additional $3.1tn could be made available for public spending annually - equivalent to 5% of global GDP. In most countries, the losses from tax evasion are greater than the total amount spent on healthcare [see figure 8].[x]

The urgent need to ensure tax rules are more effectively enforced was reiterated by the European Parliament in March 2011. In a resolution on innovative financing at the global and European level, it estimated that the cost of tax fraud in Europe is between €200-250 ($270-$330) annually.[xi] More recently, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimated that up to $100bn could be made available to G20 nations if tax evasion was prevented.[xii]

Taxation as Sharing

Preventing the excessive leakage of revenues through tax evasion and avoidance is perhaps the first and most important step governments can take to secure additional financial resources and strengthen the sharing economy. The implementation of more effective international regulations for cooperation, transparency and accountability on tax issues would have a huge impact on tax incomes in both developing and developed countries. Such measures include the sharing of information and tax data between countries, the disclosure of the true beneficial owners of companies, and a ‘country-by-country reporting' standard for multinational corporations to ensure they are being taxed appropriately when operating in multiple countries.[xiii] The principle of ‘unitary taxation', which enables subsidiaries of corporations in different countries to be treated as a single entity for tax purposes, would also make avoidance far more difficult.[xiv]

Strengthening tax systems is particularly important in developing countries if they are to channel additional finances into social services and public investments, and eventually end indebtedness and aid dependence. Not only does tax play a fundamental role in redistributing wealth to reduce poverty and inequality, the role of tax in strengthening government accountability is increasingly recognised as a crucial part of democratic state building.[xv] By its very nature, taxation is redistributive and one of the most effective tools available to governments for sharing financial resources more equitably among citizens and nations.

There is a clear understanding of what both rich and poor countries should aim towards: broad-based tax systems that redistribute wealth by seeking to levy more taxation on those with a greater ability to pay; the taxing of capital and resource consumption, rather than applying more regressive taxes such as VAT; and the effective taxation of multinational corporations. These are essential components in the creation of more just and equal societies, and must be staunchly advocated for by concerned citizens in all countries.

How much revenue could be mobilised

Ending all forms of tax evasion and avoidance globally is a tall order, but has the potential to increase government revenues around the world by many trillions of dollars each year. Similarly, strengthening tax systems in the Global South and adopting more progressive taxation policies in rich countries could raise substantial additional revenues [see table 2].

As a minimum, it is high time that governments clamp down on the use of tax havens by high-net-worth individuals and prevent the practice of tax avoidance by multinational corporations [see box]. According to conservative calculations, these measures alone could raise an annual sum of more than $349bn globally which could be used by governments to safeguard the basic needs of citizens, reduce inequality, fight climate change and meet broader international development commitments.

-

Preventing high-net-worth individuals from investing their assets in tax havens could raise an additional $189bn annually in tax revenue globally.[xvi]

-

Preventing multinational corporations from using trade mispricing and false invoicing to artificially boost their profits would secure an additional $160bn annually for developing countries.[xvii]

BOX 12: Tax avoidance around the world

Tax havens enable wealthy individuals and corporations to invest their funds in relative secrecy by using ‘off-shore' virtual financial centres outside of national jurisdictions. As normal regulations don't apply in tax havens, investors are able to avoid paying taxes on these investments, depriving governments all over the world of many billions of dollars in revenues each year.

There could be more than 80 ‘secrecy jurisdictions' worldwide, and it is estimated that around a half of all world trade and all banking assets and a third of all corporate investment passes through these tax havens.[xviii] In the US, multinational corporations and banks are avoiding at least $37bn in taxes ever year through tax havens alone.[xix] At the same time, the Tax Justice Network conservatively estimate that a global super-rich elite held between $21 to $32tn of private financial wealth in offshore bank and investment accounts by the end of 2010, a figure that far exceeds previous estimates [see note].[xx] Of this extraordinary amount, up to $9.3tn of unrecorded offshore wealth was amassed by 139 developing countries - more than double their $4tn external debt [see table 2].[xxi] The implications in terms of lost tax revenue are immense, even by the most conservative of calculations. If the same funds were not invested in tax havens, this unrecorded wealth could have generated tax revenues of at least $189bn per year, more than twice the $86bn that OECD countries as a whole are now spending on overseas development assistance.[xxii]

Tax havens also facilitate corruption by providing an efficient way for individuals, criminal organisations and corporations to hide the proceeds of illicit activities. The looting of mineral resources in African countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo is one such example. A report by Global Financial Integrity calculated that, for developing countries alone, cross-border flows from the proceeds of criminal activities, corruption and tax evasion have increased by 18% since 2000 to $1.26tn per year by 2008.[xxiii] The impact on poverty eradication and development prospects in the South is devastating; for every dollar of aid they receive, developing countries are robbed of close to $10 through illicit financial flows.[xxiv] While tackling tax havens will not end corruption, it will hamper the ability of powerful elites to transfer illegally acquired funds into bank accounts abroad.[xxv]

Corporate Trade Mispricing

As part of their relentless drive to maximise profits and shareholder returns, MNCs do whatever they can to avoid paying taxes. As much as two thirds of all international trade occurs within units of the same corporation, and their ability to operate in multiple countries through numerous subsidiary companies enables them to manipulate their costs internally in order to minimise tax payments.[xxvi]Goods are bought and sold between subsidiaries of the same company in a way that shifts profits to countries where zero or nominal taxes are payable (such as tax havens), while costs are shifted to countries with higher tax rates so that they can offset taxable profits.

Transfer pricing accounts for as much as 60% of all corporate tax avoidance in some countries.[xxvii]Examples include ballpoint pens valued at $8,500 each from Trinidad, or apple juice from Israel valued at $4,121 a litre.[xxviii] Most instances of mispricing are not so extreme, but this dishonest practice allows MNCs to avoid paying over $100bn in taxes to developing countries each year.[xxix]Publish What You Pay report that over $110bn ‘disappeared' through the mispricing of crude oil alone in the US and EU between 2000 and 2010.[xxx]

Corporations often combine transfer pricing with ‘false invoicing' and ‘reinvoicing' as a means to further maximise profits.[xxxi] This occurs between unrelated corporations who collude with one another to fix the price of goods and services traded between them, enabling each to minimise their tax losses. Together, these illicit practises are sometimes referred to as ‘trade mispricing' which Christian Aid estimates can deprive developing countries of up to $160bn a year.[xxxii]

Regressive Tax Policies

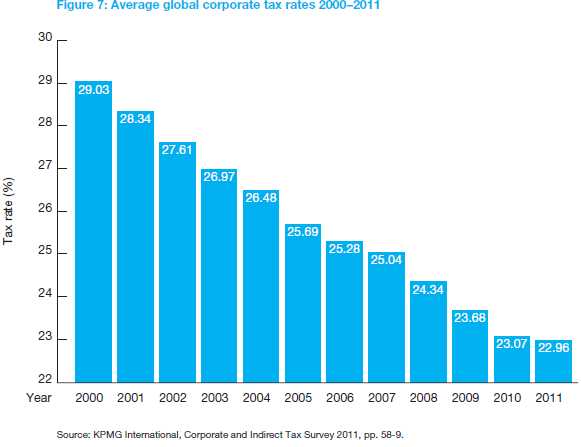

Recent decades have seen a significant decrease in how much governments around the world are willing to tax corporations and wealthy individuals. KPMG's annual corporate and indirect tax surveys reveal that official corporate tax rates reduced from 38% in 1993 to 24.9% in 2010.[xxxiii] At the same time, governments are increasingly offering significant tax incentives as a way of attracting more foreign direct investment. These can include tax exemptions, tax holidays, or even the creation of ‘special economic zones' which provide an extensive range of tax breaks to large foreign companies over a number of years, often at the expense of local businesses. There is now sufficient evidence to suggest that many of these incentives impact negatively on development, and their ability to attract investment can be severely undermined by the resulting loss of tax revenues.[xxxiv] Evidence also suggests that these subsidies are largely unnecessary, ineffective in attracting foreign direct investment, and can distort investment patterns.[xxxv]

Over the last few decades, much of the wealth generated from economic growth in developed countries has concentrated in the hands of the rich, whereas the tax burden has shifted towards those on lower incomes. Households in the US with incomes of $1m or more pay only 23% of their incomes in tax, almost half as much as they did in 1961. While the population in the US has grown by 70% over the same period, the number of people earning over a million dollars has increased by almost 1,000%.[xxxvi]

Demanding international tax justice

The issues of tax avoidance and illicit financial flows have become a major priority for civil society campaigners in recent years. In the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008, many NGOs began focusing on global tax justice as a solution to proposed cuts in public spending in the North, as well as being an avenue for developing countries to end indebtedness and finance poverty eradication from their own resources.

A breakthrough was made at the London G20 Summit in April 2009 when Gordon Brown pledged to crack down on tax havens that siphon off money from developing countries. Moves to combat tax evasion have since intensified after the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published a black list of tax havens, which paved the way for the naming and shaming of countries that fail to comply with internationally agreed standards.[xxxvii] More recently, legislation called The Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act was re-introduced in the US Congress which could help combat offshore secrecy, tax evasion and corruption.[xxxviii] The European Commission has also made a proposal for country-by-country reporting for extractives industries,[xxxix] as well as a proposal for a Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base which could be adopted in 2012.[xl]

International cooperation on tax

Following the G20 Summit in Cannes in November 2011, however, many campaigners have expressed disappointment in the lack of progress in fighting tax evasion at the G20, OECD or European Union. According to a scorecard rating the G20 on tax issues by a coalition of NGOs, its 2009 commitments have been translated to decisive action on only one of 12 suggested actions, with tentative progress on only three other issues.[xli] Although the European Union and OECD have developed tools to combat tax evasion and other harmful tax practices, they have clearly not put an end to the problems. These institutions may represent significant experience in the field, but they work primarily for their members, mostly the rich countries, and do not reflect many of the more comprehensive demands of civil society groups.

Furthermore, many countries still refuse to make details of individuals' financial worth available to the tax authorities in their home countries as a matter of course.[xlii] The OECD in particular is seen to lack legitimacy as too many of its prominent members are tax havens, leading to calls for a more inclusive and representative global forum at the United Nations. Some 50 civil society organisations have called on governments to create an Intergovernmental Commission on International Cooperation on Tax Matters to protect nations - particularly the least developed - from abusive practices, including evasion and the race to the bottom in corporate taxation.[xliii]

Reinforcing domestic tax systems

On the domestic front, there have been signs that a shift towards more progressive taxation policies is occurring in the face of severe sovereign debt crises in some industrialised countries. In August 2011, the American billionaire Warren Buffet and a group of France's wealthiest individuals made news headlines by calling on their governments to tax the rich at higher rates in order to help plug the budget deficit in both countries.[xliv] Several countries have debated the introduction of new so-called wealth taxes - a levy on a person's net worth - to help spread the burden of financial austerity. Spain has already reintroduced wealth tax legislation for those with over €700,000 in assets.[xlv] In the US, the Fairness in Taxation Act was introduced in March 2011 by Representative Jan Schakowsky, which would add five additional tax brackets for income over $1m and generate $60-80bn a year if passed.[xlvi] During the Presidential elections in France in early 2012, François Hollande even proposed a marginal tax rate of 75% on incomes over €1m a year - a level far in excess of top rates elsewhere in Europe.[xlvii]

Not all trends are going in the right direction, however, as highlighted by the UK government's plans to drastically cut corporation tax and to controversially water down anti-tax haven rules - measures that could cost the UK, as well as developing countries, many billions of dollars.[xlviii] There is clearly still a long way to go when corporate tax evasion alone continues to cost developing countries more than they receive in official development assistance. Yet the current financial crisis presents civil society with an unprecedented opportunity to communicate the importance of robust and progressive tax systems to policymakers and the wider public. The call for tax justice, both nationally and globally, represents the single most practical way for governments to raise the resources needed to reduce wealth disparities and end poverty in developing countries.

Learn more and get involved

Citizens for Tax Justice: A public interest research and advocacy organization focusing on federal, state and local tax policies and their impact upon the United States. <www.ctj.org>

Closing the Floodgates: A major report with the most comprehensive review ever published of the nature and scale of the tax problem, and a series of recommendations for how governments and international agencies might tackle them. Published by the Tax Justice Network in 2007.

<www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/Closing_the_Floodgates_-_1-FEB-2007.pd...

End Tax Haven Secrecy: A coalition of organisations campaigning from around the world, brought together to end tax haven secrecy for the benefit of the world's poorest. <www.endtaxhavensecrecy.org/en>

The Financial Secrecy Index (FSI): A ranking which identifies the jurisdictions that are most aggressive in providing secrecy in international finance, and which most actively shun co-operation with other jurisdictions. Developed by the Tax Justice Network. <www.financialsecrecyindex.com>

Offshore Watch: A forum for discussion and analysis of offshore tax havens, provided by the Association for Accountancy and Business Affairs. <visar.csustan.edu/aaba/jerseypage.html>

Publish What You Pay (PWYP): A global network of civil society organisations that are united in their call for oil, gas and mining revenues to form the basis for development and improve the lives of ordinary citizens in resource-rich countries. <www.publishwhatyoupay.org>

Tackletaxhavens.com: A major programme designed by the Tax Justice Network to raise public awareness of tax havens: what they are, the damage they do and how we can tackle them together. <www.tackletaxhavens.com>

The Task Force on Financial Integrity and Economic Development: A coalition of civil society organizations and more than 50 governments working together to address inequalities in the financial system. <www.financialtaskforce.org>

Tax Havens - How Globalization Really Works: An up-to-date evaluation of the role and function of tax havens in the global financial system - their history, inner workings, impact, extent, and enforcement. Published by Cornell University Press, 2010, and written by Ronen Palan, Richard Murphy and Christian Chavagneux.

Tax justice advocacy toolkit: An interactive tool that can be revised and improved according to new findings on tax justice issues. See also the major report published by Christian Aid and SOMO in January 2011. <www.taxjusticetoolkit.org>

Tax Justice Network: Formed in 2003, TJN promote transparency in international finance and oppose secrecy through high-level research, analysis and advocacy in the field of tax and regulation. <www.taxjustice.net>

Trace the Tax campaign: Tax rules explained in a two-part video as part of Christian Aid's campaign to end tax haven secrecy.

<www.christianaid.org.uk/ActNow/trace-the-tax/background.aspx>

Treasure Islands: A book published in 2011 by Nicholas Shaxson about dirty money, tax havens, and the "most secretive chapter in the history of global economic affairs".

Notes:

[i] OECD Revenue Statistics: Comparative Table, OECD, Paris, 2009. Quoted in ActionAid UK,Accounting for Poverty: How International Tax Rules Keep People Poor, September 2009, p. 17.

[ii] Note: ActionAid point out that ‘with political will and external assistance, such an increase could be achieved within a decade.' See: ActionAid UK, ibid, p. 13, footnote 27.

[iii] James Henry, The Price of Offshore Revisited, Tax Justice Network, July 2012.

[iv] Oxfam UK, ‘Tax haven crackdown could deliver $120bn a year to fight poverty - Oxfam', press release, 13th March 2009.

[v] Dev Kar and Carly Curcio, Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2000-2009, Washington D.C., Global Financial Integrity, January 2011.

[vi] Michael Keen and Alejandro Simone, Is Tax Competition Harming Developing Countries More Than Developed?, Tax Notes International, 28th June 2004.

[vii] Citizens for Tax Justice & the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Corporate Taxpayers & Corporate Tax Dodgers 2008-10, November 2011.

[viii] Sarah Anderson et al, Executive Excess 2011: The Massive CEO Rewards for Tax Dodging, Institute for Policy Studies, August 2011.

[ix] European Network on Debt & Development (Eurodad), ‘EU corporate tax base harmonisation proposal may actually increase tax competition', 27th October 2011, <www.eurodad.org>

[x] Tax Justice Network, The Cost of Tax Abuse: A briefing paper on the cost of tax evasion worldwide, November 2011, see table on p. 3.

[xi] European Parliament, Resolution of 8 March 2011 on innovative financing at global and European level, INI/2010/2105, Note 14.

[xii] Larry Elliott and Patrick Wintour, ‘Tax evasion crackdown will raise £62bn for G20 nations, says OECD', The Guardian, 3rd November 2011.

[xiii] For more information, see: <www.tackletaxhavens.com/the-solutions/>

[xiv] Sol Picciotto, ‘Another Step Towards Unitary Taxation?', Tax Justice Network, 10th June 2009, <www.taxjustice.blogspot.com>

[xv] Deborah Brautigam (ed), Taxation and State-Building in Developing Countries: Capacity and Consent, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

[xvi] See box for note on calculation. Source: James Henry, The Price of Offshore Revisited, Tax Justice Network, July 2012.

[xvii] Figure based on estimates of corporate tax losses to the developing world from transfer mispricing and false invoicing. See Christian Aid, Death and taxes: the true toll of tax dodging, May 2008, pp. 51-53.

[xviii] Nicholas Shaxson, Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men Who Stole the World, The Bodley Head, 2011, p. 8, see note 2. Latest estimates from the Tax Justice Network are now that more than 80 tax havens exist worldwide, see: James Henry, op cit.

[xix] Scott Klinger et al, The Business Case Against Overseas Tax Havens, American Sustainable Business Council, Business for Shared Prosperity and Wealth for the Common Good, 20th July 2010, p. 3.

[xx] Note that the difficulties in detailing hidden assets in some countries - owing to restrictions on getting access to data, as well as other technical limitations - means that the actual figure is conservatively estimated to be between $21 to $32tn, as of 2010. Yet the latter sum is larger than the entire American economy. Furthermore, these figures include only financial wealth, not other non-financial assets that are also owned via offshore structures such as real estate, yachts, race horses, gold bricks etc. See James Henry, The Price of Offshore Revisited, op cit.

[xxi] Nick Mead, 'Developing world's secret offshore wealth 'double external debt', The Observer, 22nd July 2012.

[xxii] This is assuming that global offshore financial wealth of $21tn earns a total return of just 3% a year, with an average marginal tax rate of 30% in the home country. Of course, serious challenges need to be overcome if this offshore wealth is to be located and rules put in place to divvy up the proceeds fairly. In practice, many developing countries do not have effective domestic income tax regimes in place, let alone the power to enforce such taxes across borders. See James Henry, op cit.

[xxiii] Dev Kar and Carly Curcio, Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2000-2009, Washington DC, Global Financial Integrity, January 2011.

[xxiv] D. Jakob Vestergaard and Martin Højland, Combating illicit financial flows from poor countries Estimating the possible gains, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS); DIIS Policy Brief, November 2009.

[xxv] Global Witness et al, The links between tax evasion and corruption: how the G20 should tackle illicit financial flows, A briefing paper by Global Witness, Tax Justice Network, Christian Aid, and Global Financial Integrity, September 2009.

[xxvi] Note: In a personal communication, John Christensen of the Tax Justice Network states that the OECD was the original source for this estimate but blows hot and cold on its accuracy, however a likely estimate would be in the range of between 40-60% of international trade. Source: Christian Aid, Death and taxes: the true toll of tax dodging, May 2008.

[xxvii] Prem Sikka and Hugh Willmott, The dark side of transfer pricing: Its role in tax avoidance and wealth retentiveness, Critical Perspectives on Accounting 21 (2010), p. 342-356.

[xxviii] Prem Sikka and Colin Haslam, Transfer Pricing and its Role in Tax Avoidance and Flight Of Capital: Some Theory and Evidence, University of Essex, undated.

[xxix] Ann Hollingshead, ‘The Implied Tax Revenue Lost from Trade Mispricing', Global Financial Integrity, February 2010, p. 1.

[xxx] Simon J. Pak, Lost billions. Transfer Pricing in the Extractive Industries, Publish What You Pay, January 2012.

[xxxi] In a personal communication, John Christensen of the Tax Justice Network notes that the practice of 'reinvoicing' involves an exporter or importer using an apparently third party company - typically based in a tax haven jurisdiction - to underprice exports or overprice imports, which are subsequently repriced via the offshore entity (often operated by an agency). Either way, profits are shifted offshore to an apparently unrelated company which in practice is either wholly or partly owned and controlled by the exporter/importer. This practice is very widespread but almost entirely unresearched and unquantified.

[xxxii] Christian Aid, Death and taxes: the true toll of tax dodging, May 2008, pp. 51-53.

[xxxiii] KPMG International, Corporate and Indirect Tax Rate Survey, June 2007; KPMG International,Corporate and Indirect Tax Rate Survey, September 2010.

[xxxiv] Christian Aid, Tax justice advocacy toolkit: a toolkit for civil society, January 2011, p. 12. See the studies listed at reference 34.

[xxxv] Diana Farrell, Jaana K. Remes, and Heiner Schulz, The truth about foreign direct investment in emerging markets, in The McKinsey Quarterly 2004, Number 1.

[xxxvi] Chuck Collins et al, Unnecessary Austerity, Unnecessary Shutdown, Institute of Policy Studies, April 2011. [xxxvii] Nicholas Watt, Larry Elliott, Julian Borger and Ian Black, ‘G20 declares door shut on tax havens', The Guardian, 2nd April 2009.

[xxxviii] Global Witness, ‘Global Witness calls on Congress to pass Tax Havens Bill to curb money laundering and tax dodging', Press Release, 12th July 2011. Note that the Bill was first introduced in February 2007 by Senators Levin, Coleman and Obama as sponsors.

[xxxix] European Network on Debt & Development, ‘EU proposal helps curb corruption but fails to tackle tax dodging', 25th October 2011.

[xl] Eurodad, ‘EU corporate tax base harmonisation proposal may actually increase tax competition', 27th October 2011.

[xli] Eurodad et al, G20 action on tax and development: A progress report card, 9th November 2011.

[xlii] Heather Stewart, '£13tn hoard hidden from taxman by global elite', The Guardian, 21st July 2012.

[xliii] Social Watch, Tax Justice Network and Eurodad, ‘Civil Society Claims for an Intergovernmental Commission On Tax Cooperation', Sign-on letter, 1st July 2011.

[xliv] Kim Willsher, France's rich keen to pay more tax as PM Fillon announces 'rigour package', The Guardian, 24th August 2011.

[xlv] Victor Mallet, ‘Spain revives wealth tax plan amid crisis', Financial Times, 13th September 2011.

[xlvi] Chuck Collins et al, Unnecessary Austerity, Unnecessary Shutdown, Institute of Policy Studies, April 2011, p. 13.

[xlvii] Hugh Carnegy, ‘Hollande proposes 75% top tax rate', Financial Times, 28th February 2012.

[xlviii] ActionAid, Collateral damage: How government plans to water down UK anti-tax haven rules could cost developing countries - and the UK - billions, Briefing paper, March 2012.

Image credit: Oxfam Canada, flickr creative commons