Key points:

- Developed countries spend $374bn supporting their agricultural sectors each year, the majority of which goes to large-scale wealthy farmers and agribusinesses.

- The economic impacts of agricultural subsidies in developed countries can be devastating for small-scale and family-run farms that continue to disappear each year.

- Millions of smallholder farmers in developing countries are unable to compete with cheap, subsidised imports of agricultural commodities from rich countries and either abandon their livelihoods or get pushed deeper into poverty.

- The industrial model of production and consumption that OECD subsidies sustain is environmentally destructive, causes excessive pollution, and contributes a major proportion of global carbon emissions.

- Eliminating inappropriate and wasteful agricultural subsidies is likely to require steep cuts, in the range of 50% across OECD countries. This could raise $187bn annually to prevent hunger and deprivation in the Global South.

- The remaining subsidies in OECD countries should be re-oriented to support a transition to more localised and agroecological farming practices based upon the principles of food sovereignty.

Global food systems are experiencing a severe crisis: despite the production of more than enough food to feed the world's population, life-threatening food emergencies continue to devastate many developing countries and almost a billion people are now hungry - one in seven of the global population.[1]Governments are also facing immense challenges stemming from climate change, environmental degradation and rising populations, while the increasing demand for meat and biofuel production is set to further intensify the pressure on agricultural land over coming decades.

The structural causes of these interlinked issues are complex and include unfair international trade rules, the impact of financial speculation and the growing power and concentration of multinational agri-corporations. But underpinning the crisis in food systems is the ‘modern' style of industrial agriculture that is largely sustained by the colossal subsidies paid to a minority of farm operations in rich countries.

These subsidies continue to favour large, industrialised producers at a time when experts are calling for greater support for smallholder farmers using environmentally sustainable practices, alongside more localised production and consumption. The evidence now overwhelmingly suggests that ‘agro-ecological' food production - which entails small-scale farms growing a larger variety of crops using very few chemical inputs - is the most efficient way to meet development and sustainability goals of reducing hunger and poverty, improving nutrition, health and rural livelihoods, and facilitating social and environmental sustainability [see box 14 below].[2]

Reforming agricultural subsidies alone will not address the root causes of the agricultural crisis, but significantly reducing the most perverse subsides could help protect millions of small-scale farmers throughout the world as well as help safeguard the environment. At the same time, these reductions would enable governments to raise billions of dollars each year that could be better spent promoting agro-ecological farming practices and increasing food security in developing countries.

Subsidies for the few

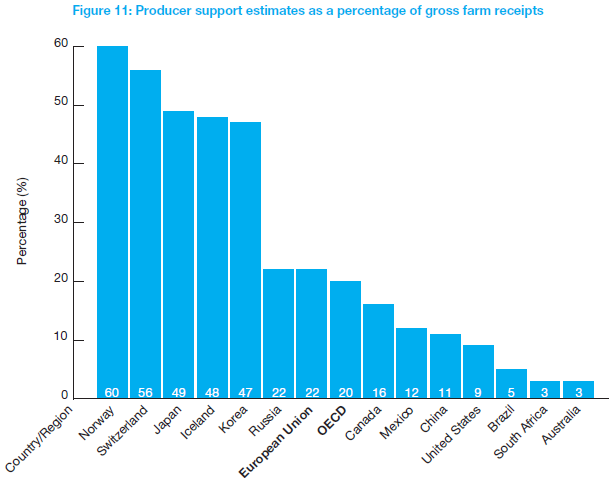

The amount of public revenue spent by governments to support farmers in the 34 countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been steadily declining in recent years, but still remains considerable. In 2010, these countries spent in excess of $1bn a day ($374bn annually) supporting their agricultural sectors. Of this, subsidies given directly to farmers (called producer support) totalled $227bn a year, which accounted for an average of 20% of farm profits [see figure 11].[3]

These huge agricultural subsidies are currently distributed in a highly regressive manner, meaning that they accrue mostly to large farms and agribusinesses and neglect smaller farm operations. A major example is the European Union's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which is meant to ensure a fair standard of living for agricultural producers in Europe. In reality, around 80% of direct income support goes into the pockets of the wealthiest 20% of farms - mainly big landowners and agribusiness companies.[4]

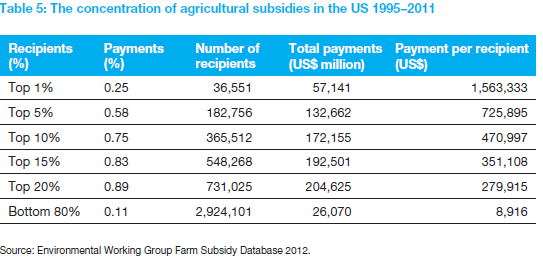

The EU does not release the full details of subsidy recipients, but a watchdog found that in 2010 at least 1,330 payments of more than €1m (US$1.3bn) were handed out to big farms across Europe.[5] Farm subsidies under CAP amount to approximately €55bn a year (US$74bn), just over 40% of the EU's entire annual budget,[6] for a sector that accounts for less than 2% of employment across the region. The picture is similar in the United States, where only 38% of farms receive any government support; in 2011, the top 10% of these farms collected 75% of all subsidies.[7] Over $277bn was paid out in subsidies between 1995 and 2011, but 62% of US farmers did not collect any subsidy payments at all [see table 5].[8]

Smaller farmers struggling to compete often incur unpayable debts which drive them into bankruptcy, and their lands are then consolidated into those of the largest and wealthiest farmers. In Europe, 200,000 farmers gave up agriculture in 1999 alone.[9] According to a census published by Eurostat, the EU has lost 3 million farms between 2003 and 2010.[10] Possibly more than a thousand farms continue to disappear across Europe every day, mainly as a result of the lack of political will on the part of governments and international institutions to back local, family-scale and smallholder agriculture.[11]

Similarly in the US, more than 90,000 farms of less than 2,000 acres were lost in just five years from 1997 to 2002, while farms above 2,000 acres increased by more than 3,600.[12] Yet small farms continue to be a vital part of the rural economy, employing the vast majority of agricultural labourers in many OECD countries and producing the majority of agricultural goods. This is despite being the persistent losers in agricultural support programmes that favour highly mechanized and capital-intensive farm operations.

Notwithstanding the social problems caused by the elimination of the family farm and the concentration of land, resources and production, many agricultural subsidies also serve to exacerbate environmental damage. The industrial model of production and consumption that OECD subsidies sustain is based on intensive energy use, and is highly dependent on external capital and chemical inputs. This is accompanied in many instances by environmental degradation such as soil erosion, salinization, pollution by pesticides and nitrogen-rich farm effluent, as well as the excessive use of natural resources. It also contributes to most of the greenhouse gas emissions released by agriculture, livestock production and fisheries.[13] With the huge level of support given to industrial agriculture, the costs of ecological depletion remain largely external to the market.

Impacts in the Global South

One of the main negative effects of subsidies in the EU and US is to stimulate the overproduction of ‘cash-crops' such as corn, wheat or soybean, vast quantities of which are then sold on international commodity markets at artificially low prices. Further constrained by unfair trade rules, smallholder farmers in developing countries increasingly find themselves unable to produce goods that are cheaper than the subsidised imports from rich countries that flood local markets. This so-called ‘food dumping' - when surpluses are sold at below the cost of production - undermines the livelihoods of local farmers who cannot compete with the artificially low prices and are often driven out of their jobs, further increasing the market share of larger producers such as those in the US and Europe.

Many industrialised nations have taken some steps in recent years towards reducing the extent to which agricultural subsidies impact on food security in developing countries. Nonetheless, their subsidies still stimulate artificially cheap exports and cause significant harm to small producers in the Global South.[14] For example, agricultural analyst Jaques Berthelot demonstrates that EU animal products sold on the world market received, on average, subsidies equalling a third of their export value in the period 2006-2008.[15] This decreases the world market price for the products and affects producers in the South by reducing their incomes, disrupting local markets and displacing exporters. European milk dumping alone can potentially affect up to 900 million people estimated to live in dairy farming households, the vast majority of whom are impoverished small farmers.[16]

In recent years, negotiations at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) have particularly focussed on reducing agricultural subsidies that distort trade and lead to dumping by introducing a classification system for farm payments. However, wealthy countries reclassify much of their payments as ‘permissible' even when it continues to encourage overproduction or harm farmers in the South.[17]WTO agreements have also permitted rich countries to maintain high import tariffs on many agricultural products, which act as a barrier to small farmers trying to export their goods to foreign markets. Furthermore, the severe crisis in smallholder farming across the world is connected to bilateral and regional free trade agreements that have further reduced import tariffs for developing countries, preventing them from protecting their farmers from subsidised and artificially cheap produce from rich countries [see section 10 on import tariffs in this report].

Together, unjust OECD subsidies and free trade agreements lead to a loss of income and employment in the South, and contribute to a ‘rural exodus' in many developing countries as small farmers abandon their plots of land and head to cities in search of jobs. The majority of these migrants usually find themselves living in urban slum communities, often in deprived conditions and with no additional opportunities for economic or social security.[18] In sum, the subsidy system in rich countries perpetuates an unfair trading system, undermines the development chances of some of the poorest producers in the world, and lies at the root of serious environmental degradation. Clearly, a system that spends billions of dollars in OECD countries to sustain an unjust and unsustainable model of agriculture is in need of fundamental reform.

Radically reforming the subsidy system

Although governments in developing countries also provide some degree of financial support to their agricultural sectors, especially in emerging economies, these subsidies still remain relatively low compared to the OECD average [see note].[19] Most developing countries simply do not have the same financial resources, or the flexibility within WTO negotiations, to support their producers to the same degree as the industrialised nations.

The priority of subsidy reform efforts should therefore be targeted at OECD countries, particularly within the EU and US where agricultural support reaches the highest levels and the vast majority ends up as windfall profits for the wealthiest farmers and largest agro-corporations. In particular, ending those subsidies that facilitate the overproduction and export of artificially cheap produce could halt the practice of food dumping and provide a significant stimulus for rural economies in developing countries, which in turn could increase incomes and improve food security.

Eliminating these ‘bad' subsidies would free up significant government resources that could be used for worthier causes. In the US alone, the Green Scissors campaign estimates that $11bn annually could be saved in cuts to selected agricultural subsidies that are wasted on corporate welfare to agribusiness and fail to address the needs of the majority of America's farmers.[20] If the level of domestic subsidies across OECD countries is reduced by an average of 50%, $187bn could be raised by governments and used instead to reduce poverty and increase food security in developing countries [see below].

However, agricultural subsidies per se are not the problem. Smallholder farmers everywhere, in North and South, need public sector support for food production and rural development. These ‘good' subsidies should be augmented in OECD countries by redirecting the remaining level of support to smallholders and agroecological farming practices. Redistributing these payments away from agribusiness corporations would facilitate employment within the farming sector and help keep family farmers on the land, support vibrant rural economies, assist with soil conservation, and support the urgently-needed transition to a sustainable food system - one that reflects the realities of 21st Century agriculture.

In the end, reforming subsidies is only part of the answer to resolving the crisis in agriculture and must be accompanied by much wider reforms to the world's food systems. As campaigned for by progressive farm groups worldwide, there is a critical need to establish fairer regional and global trade arrangements that comply with the 'food sovereignty' framework.[21] The aim for governments should be to establish higher levels of food self-sufficiency and reduce dependency on imports, both within OECD countries and across the Global South. One central demand of smallholder farmers is for a fair and reliable price for the produce they sell, which requires the wide implementation of supply management policies to regulate production and help raise commodity prices for farmers. Moreover, the goal of rural and agricultural development needs to be given additional support across OECD countries where policies should aim to diversify and improve future employment opportunities in the farming sector, particularly for smallholders.[22]

How much revenue could be mobilised?

Given that a significant proportion of OECD subsidies are ultimately spent supporting large agri-corporations and industrial agricultural practices, steep cuts to existing levels of domestic subsidies are necessary. As a minimum, these cuts should eliminate those subsidies that facilitate the overproduction and export of artificially cheap produce to developing countries (including indirect and hidden subsidies).

Reducing agricultural subsidies by an average of 50% across OECD countries could raise $187bn, which could instead be used to tackle poverty and increase food security in the Global South. Remaining subsidies should be re-oriented to support small-scale producers and agro-ecological farming practices, alongside wider reforms to agriculture based upon the principles of food sovereignty.

50% reduction in total OECD agricultural support = $187bn per year [see note][23]

* * * * * * * *

Fixing the farm subsidy regime

Subsidies have been a key stumbling block in trade negotiations ever since agriculture was included in the World Trade Organisation agreement at its inception in 1995. The Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) has long been criticised by civil society groups for reducing tariff protections for small farmers, while allowing rich countries to continue paying their farmers massive subsidies that developing countries cannot afford. In effect, the AoA locked in the disadvantages and unequal playing field that developing countries already faced in agricultural commodity markets. Considerable contention has existed both against and between the EU and US in subsequent negotiations over their maintenance of subsidies, which are seen to operate effectively as barriers to free trade.

Following the start of the Doha ‘development' round of trade talks in 2001, many campaigners focused on the subsidies issue with the oft-heard claim that while nearly three billion people in the world are forced to live on less than $2 a day, the average European cow receives more than that amount in government subsidies.[24] At the Cancun Ministerial in 2003, the new ‘Group of 21' countries - led by some of the developing world's most important agricultural producers and exporters, including Brazil, India and China - demanded a rapid phase-out of agricultural subsidies in the US, EU and Japan.[25]

The US in particular was not only unwilling to cut subsidies, but continued to expand agricultural protections to appease domestic interests - in fact almost doubling subsidies on some products in the preceding US farm bill in 2002,[26] and increasing them again in a five-year programme of subsidies in 2008.[27] Subsidy levels in both the US and EU have since decreased in recent years, especially from 2006 onwards. With the rise in global food prices, subsidy levels have reduced in those countries where part of the support to farmers is linked to low prices, although total subsidy levels still remain considerable for most OECD countries.

Ending the ‘boxing match' in agricultural trade

A favoured tactic of the ‘subsidy superpowers' in WTO ministerial meetings has been to redefine subsidies according to the box categories of permitted farm payments (the ‘hide the subsidy' shell game), rather than significantly cutting overall support.[28] Green box payments - those that are meant to cause no more than minimal distortion of trade or production - remain exempt from the WTO's subsidy spending limits, and now comprise nine-tenths of the subsidies in the US,[29] as well as a record amount of subsidies in the EU.[30] Yet many experts contest that green box payments continue to have a trade-distorting and surplus-stimulating effect owing to their sheer size, and for often being concentrated on the largest and most productive farms.[31] For example, the EU may well have offered to reduce trade distorting subsidies by 80% through the WTO negotiations and to eliminate farm export subsidies altogether, but it still provides an enormous level of domestic support to EU farmers that enables the export of European wheat products at dumping prices.[32]

The WTO has thus proven itself an unlikely venue for achieving meaningful reductions in agricultural subsidies. Failure to reach agreement about reducing subsidies was a key reason for the standstill in all WTO negotiations since the Doha Round began, including at the collapse of talks in Geneva, July 2008.[33] A major problem is the significant political support that domestic farm programmes receive in OECD countries, as few politicians are willing to challenge the powerful ‘Big Ag' lobby that directly influences the negotiating positions of the EU and US in the WTO. The thousands of lobbyists based in Washington and Brussels, often outnumbering parliamentary officials and lawmakers, ensure that the interests of multinational corporations are placed well ahead of poor people's livelihoods in the South.

The folly of Big Ag

Despite extensive and ongoing subsidy reform processes, policymakers within the EU and US continue to favour the vested interests that prevent subsidy programs from sustaining small family farms and promoting the wider public interest. According to campaign groups, US subsidies are still co-opted to support plantation-scale production of corns, soybeans, rice, cotton and wheat, while failing to act as a safety net for working farm and ranch families.[34] Trade campaigners have also criticised the European Commission proposals on a reformed Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for dropping every reference to Europe's development obligations.[35] In the longstanding debate on CAP reform, its external dimension - in terms of its strong influence on the state of poverty and food insecurity in the world - remains only marginal to discussions.[36]

Agricultural subsidies are a foremost example of unfair trade and the unequal distribution of government support in favour of large, input-intensive and export-oriented industrial producers. Fundamentally redirecting these subsidies is an urgent priority if the world is serious about benefiting the poor and protecting the environment. In the context of a global financial crisis that is costing millions of people their jobs, it makes no economic or moral sense to continue handing out taxpayers money to some of the most destructive agri-corporations and richest landowning individuals.

Meaningful subsidy reductions in OECD countries could mark a major step towards meeting international development goals, and could contribute significantly to a more environmentally sustainable model of agriculture. But this will only happen if governments redirect remaining domestic support towards strengthening smaller scale, more localised and regenerative models of agriculture both at home and abroad. Such a radical reform of the subsidy system is unlikely to happen without huge pressure from a wide range of civil society actors, progressive farmer groups and concerned politicians worldwide.

Box 14: New Era for Agriculture?

The following text is taken directly from a ‘Food First Backgrounder' by the Institute for Food and Development Policy, Volume 14, Number 2, Summer 2008. The article is by Marcia Ishii-Eiteman, a senior scientist at PAN North America and a lead author on the Global Report of the IAASTD. The full backgrounder is available at <www.foodfirst.org>

On April 7, 2008, as the media headlines focused on falling grain reserves, soaring food prices, and food riots, representatives from 61 nations met in Johannesburg, South Africa to adopt a UN report that proposes urgently needed solutions to the global food system's systemic problems. The International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD) asked the question: What must we do differently to overcome persistent poverty and hunger, achieve equitable and sustainable development, and sustain productive and resilient farming in the face of environmental crises?

The IAASTD study, sponsored by the UN Environment Programme, Food and Agriculture Organisation, and Development Programme; UNESCO; Global Environment Facility; and the World Bank, represents four years' work by more than 400 experts who examined the intertwined problems of global agriculture, hunger, poverty, power and influence. Their findings sent shockwaves through the conventional agriculture establishment.

Call for an agricultural revolution

"Business as usual is not an option," declared IAASTD Director Robert Watson, echoing the IAASTD's call for a radical transformation of the world's food and farming systems. The final report-endorsed by 58 governments and released worldwide on April 15, 2008-concluded that industrial agriculture has degraded the natural resources upon which human survival depends and now threatens water, energy and climate security. The report warns that continued reliance on simplistic technological fixes-including transgenic crops-is not a solution to reducing persistent hunger and could increase environmental problems and poverty. It also critiqued the undue influence of transnational agribusiness on public policy and the unfair global trade policies that have left more than half of the world's population malnourished.

The IAASTD report affirmed that we have options to change direction. By revising policies to strengthen the small-scale farm sector, increasing investments in agroecological farming and adopting an equitable international trading framework, we can establish more socially and ecologically resilient systems while maintaining current levels of productivity and improving profitability for small-scale farmers. The report's authors suggested reconfiguring agricultural research, extension and education to incorporate the vital contributions of local and Indigenous knowledge and innovation, and embrace equitable, participatory decision-making processes.

This is the first independent global assessment that acknowledges that small-scale, low-impact farming contributes crucial ecological and social functions that must be protected, and that nations and peoples have the right to democratically determine their own food and agricultural policies.

Food sovereignty: Answer to the food crisis

Today's global food crisis has been exacerbated by a number of factors: the large-scale conversion of food crops to agrofuel production, price volatility driven by rampant commodity speculation, changing diets, and climate-related production shortfalls. However, as documented by the IAASTD, the deeper roots of today's crisis lie in decades of governmental neglect of the small-farm sector, grossly unfair trade rules and Northern governments' practice of dumping food surpluses on countries in the global south at prices far below local cost of production.

These policies, together with heavy reliance on environmentally destructive industrial agricultural practices, have destroyed rural farm communities around the world, undermining their ability to produce or buy food and contributing to environmental pollution and water scarcity. The IAASTD report presents a blueprint to confront today's food crisis. We can begin to reverse structural inequities within and between countries, increase rural communities' access to and control over resources, and pave the way towards local and national food sovereignty by strengthening farmers' organizations, creating more equitable and transparent trade agreements and increasing local participation in policy formation and other decision-making processes.

The report concludes that ensuring food security and recognizing food sovereignty requires ending the institutional marginalization of the world's small-scale producers.

An inconvenient truth

The IAASTD was precedent-setting for its bold experiment in shared governance. Civil society groups (along with government and private sector representatives) participated in both authoring the report and in providing oversight and governance. History shows that governments and transnational corporations, acting on their own, have not been successful in meeting broad societal goals. The IAASTD's success has proven that active civil society participation in intergovernmental processes is critical to meeting the challenges of the 21st century.

The radical shifts proposed by the IAASTD report challenge the status quo. Syngenta walked out of the IAASTD process in its final days, complaining that their synthetic pesticides and transgenic products had not been sufficiently valued. The U.S. and Australian governments were especially stung by criticism of their trade liberalization policies, which were criticized for adverse social and environmental impacts while doing little to alleviate hunger and poverty.

Just three countries-the U.S., Australia and Canada-have refused to endorse the report. Like reports on the climate crisis, the IAASTD's findings are likely to be considered an "inconvenient truth" for the industrial agricultural establishment and the world's dominant economies.

The U.S. government, the agrochemical trade association CropLife, and other beneficiaries of the current system continue to argue loudly against change at a time when both environmentally alarming changes and global social unrest caused by grinding poverty pose a significant threat.

For more information see: <www.panna.org/jt/agAssessment>

All IAASTD documents are available at <www.agassessment.org>

Learn more and get involved

Capreform.eu: A sister project to farmsubsidy.org, working to bring greater transparency and accountability to the Common Agricultural Policy. <www.capreform.eu>

Farmsubsidy.org: With the European Union spending around €55bn a year on farm subsidies, this website helps people find out who gets what, and why. <www.farmsubsidy.org>

Food Rebellions - Crisis and the Hunger for Justice: A book by Eric Holt-Giminez and Raj Patel on the real story behind the world food crisis and what we can do about it, published by Pambazuka Press, 2009.

The Global Food Economy - The Battle for the Future of Farming: A book by Tony Weis that examines the contradictions of the current food economy, how such a system came about, and how it is being enforced by the WTO. Published by Zed Books, 2007.

Global Subsidies Initiative: Putting a spotlight on subsidies - transfers of public money to private interests - and how they undermine efforts to put the world economy on a path toward sustainable development. <www.iisd.org/gsi>

Green Scissors 2011: A coalition of environmental, taxpayer and consumer groups identify US government subsidies that are damaging to the environment and waste taxpayer dollars.www.greenscissors.com

‘Growing a Better Future: Food Justice in a Resource Constrained World': A report published in May 2011 by Oxfam to launch their new campaign with a simple message: that another food system is possible. <www.oxfam.org/en/grow/reports/growing-better-future>

IAASTD: A three-year collaborative effort (2005-2007) that assessed agricultural knowledge, science and technology for development, with respect to meeting development and sustainability goals of reducing hunger and poverty, improving nutrition, health and rural livelihoods, and facilitating social and environmental sustainability. <www.agassessment.org>

International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD): A Geneva-based organisation with a programme on agricultural trade and sustainable development that seeks to promote food security, equity and environmental sustainability in agricultural trade. <www.ictsd.org/programmes/agriculture>

Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP): A think-tank and campaign organisation based in Minnesota, U.S., that works locally and globally at the intersection of policy and practice to ensure fair and sustainable food, farm and trade systems. <www.iatp.org>

Just Trade?! An NGO project that advocates for greater policy coherence between EU development and trade policy, with a view to promoting equitable and sustainable development. <www.just-trade.org>

National Family Farm Coalition: A non-profit organisation that represents US family farm and rural groups to secure a sustainable, economically just, healthy, safe and secure food and farm system. <www.nffc.net>

Reform the CAP: Another resource for all those interested in reforming the EU's Common Agricultural Policy, helping to foster a better understanding of what is at stake and how to shape the future CAP. <www.reformthecap.eu>

The UK Food Group: The principal UK network for non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working on global food and agriculture issues, holding a vision of a more just, sustainable and fairer food system in which hunger has been eradicated, equity realised and the environment restored. <www.ukfg.org.uk>

US Farm Subsidy Database: Mapping the issue of skewed pay-outs to America's largest and richest farms, by the Environmental Working Group. <www.farm.ewg.org>

Notes:

[1] Note: according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, 925 were classified as hungry in 2011. But an unparalleled number of severe food shortages has added 43 million to this figure in 2012.

[2] International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development,Agriculture at a Crossroads: Synthesis Report, United Nations, Washington D.C., 2009.

[3] OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2011: OECD Countries and Emerging Economies, September 2011.

[4] Philippe Legrain, ‘Beyond CAP: Why the EU Budget Needs Reform', The Lisbon Council e-brief, Issue 09, 2010, <www.lisboncouncil.net>

[5] Farmsubsidy.org, 2011 Farm Subsidy Data Harvest: Millionaires and Missing Money, 10th May 2011, accessed October 2011, <www.farmsubsidy.org>

[6] Farmsubsidy.org, Let The Sunshine In, 23rd September 2011, accessed October 2011.

[7] Environmental Working Group, 2012 Farm Subsidy Database, The United States Summary Information, accessed August 2012, <www.farm.ewg.org>

[8] Ibid. See also ‘Farms Getting Government Payments, By State, according to the 2007 USDA Census of Agriculture', compiled from 2007 Census of Agriculture, April 2010, <www.farm.ewg.org>

[9] John Vidal, ‘Global trade focuses on exodus from the land', The Guardian, 28th February 2001.

[10] Eurostat Communique de presse, ‘Le nombre d'exploitations agricoles a diminué de 20% dans l'UE27 entre 2003 et 2010', 11 Octobre 2011, <www.epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu>

[11] Eric Holt-Giminez and Raj Patel, Food Rebellions: Crisis and the Hunger for Justice, Pambazuka Press, 2009, p. 66.

[12] Mark Ritchie, Sophia Murphy and Mary Beth Lake, United States Dumping on World Agricultural Markets: February 2004 Update, Cancun Series Paper no. 1, Minneapolis: Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy.

[13] UK Food Group, Securing future food: towards ecological food provision, January 2010, pp. 4-8.

[14] International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD), Ensuring trade policy

supports food security goals, ICTSD Programme on Agricultural Trade and Sustainable Development, November 2009.

[15] Jaques Berthelot, ‘The EU-15 dumping of animal products on average from 2006 to 2008', Solidarité, February 2011. Quoted in Thomas Fritz, Globalising Hunger: Food security and the EU's Common Agricultural Policy, Transnational Institute et al, November 2011, section 4.3.

[16] Ibid.

[17] International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD), Agricultural Subsidies in the WTO Green Box: Ensuring Coherence with Sustainable Development Goals, Information note no. 16th September 2009.

[18] Tony Weiss, The Global Food Economy: The Battle for the Future of Farming, Zed books, 2007, pp. 24-28.

[19] Of the emerging economies, Brazil, South Africa and Ukraine generally support agriculture at levels well below the OECD average, while support in China is approaching the OECD average. In Russia, farm support now exceeds the OECD average. However, support is generally much lower in other developing countries. See: OECD, Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2011: OECD Countries and Emerging Economies, September 2011.

[20] Figures represent an average of cuts over the period 2012-2016. See: Public Citizen, the Heartland Institute, Friends of the Earth, and Taxpayers for Common Sense, Green Scissors 2011: Cutting Wasteful and Environmentally Harmful Spending, August 2011, pp. 16-17.

[21] Peoples' Food Sovereignty Statement, La Via Campesina and the People's Food Sovereignty Network, 2006, <www.nyeleni.org/IMG/pdf/Peoples_Food_Sovereignty_Statement.pdf>

[22] See European Coordination Via Campesina (the European arm of the international small farmers movement, La Via Campesina), <www.eurovia.org/?lang=en>

[23] Note: The estimated $374bn of annual agricultural subsidies in OECD countries includes a complex array of supports, such as direct payments to producers, transfers to consumers from tax payers, support for general services to agriculture, marketing, promotion and other types of less tangible subsidies. It is beyond the scope of this report to specify which of these individual subsidies should be reduced and which should be maintained. Such decisions should be the subject of national dialogue according to individual country needs and priorities, and should not be confined to the undemocratic negotiations within the WTO.

[24] Penny Fowler, Milking the CAP: How Europe's dairy regime is devastating livelihoods in the developing world, Oxfam Briefing Paper 34, December 2002.

[25] Timothy A. Wise. The Paradox of Agricultural Subsidies: Measurement Issues, Agricultural Dumping, and Policy Reform, Global Development and Environment Institute Working Paper No. 04-02, May 2004.

[26] Sabyasachi Mitra, ‘US Farm Bill 2002: Its Implications for World Agricultural Markets', International Development Economics Association (IDEAS), 17th May 2002.

[27] The Economist, ‘The farm bill: A harvest of disgrace', Washington D.C., 22nd May 2008.

[28] Peter Rosset, Food is Different: Why We Must Get the WTO Out of Agriculture, Zed books, 2006, pp. 84-88.

[29] ICTSD, ‘Farm Subsidies: Ballooning US Food Aid Pushes Total Support to New High', 7th September 2011.

[30] ICTSD, ‘EU Halves Production-Linked Farm Subsidies, But Delinked Support Jumps', 26th January 2011.

[31] Grey, Clark, Shih and Associates, Green Box Mythology: The Decoupling Fraud, Study Prepared for Dairy Farmers of Canada, June 2006.

[32] Thomas Fritz, Globalising Hunger, op cit, pp. 46-48.

[33] Martin Khor, ‘The July failure of the WTO talks: Cause of collapse and prospects of revival', Third World Resurgence no. 215, July 2008.

[34] Environmental Working Group, ‘Despite Claims of Reform, Subsidy Band Marches On Non-farmers, Urbanites Still Receiving Farm Subsidies', Press Release, 23rd June 2011, accessed October 2011, <www.ewg.org>; Ben Lilliston, 'What's at Stake in the 2012 Farm Bill?', Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, 28th March 2012, <www.iatp.org>

[35] Daan Bauwens, Agriculture Proposals ‘Failing Development', Inter Press News, Brussels, 19th October 2011.

[36] Thomas Fritz, Globalising Hunger, op cit, p. 4.

Image credit: Panos Images