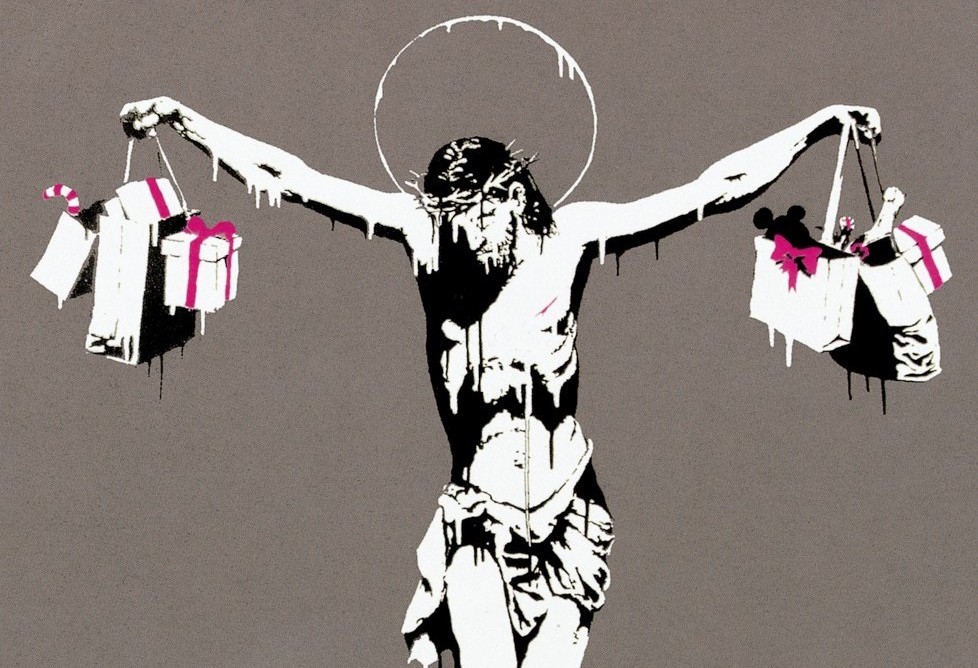

The holiday season provides us with a unique opportunity to express the new awareness that must inform a less commercialised and more sharing-oriented world. Rather than spending all our time partaking in conspicuous consumption, why don’t we commemorate Christmas by organising massive gatherings for helping the poor and healing the environment?

At this time of year, our overconsuming lifestyles in the affluent Western world are impossible to ignore. Brightly-lit shops are bursting with festive foods and expensive indulgences, while seasonal songs play in the background of shopping malls to keep us spending the money we don’t have on things we don’t need, in order to make impressions that don’t matter.

The frenetic commercialism of Christmas on the high streets continues to escalate despite all the warnings from climate scientists that ordinary Western lifestyles are destroying the planet. We still buy enough Christmas trees in the UK alone that could reach New York and back, if placed in a straight line. Enough card packaging is thrown away in this country that could cover Big Ben almost 260,000 times. Not to mention the 4,500 tonnes of tin foil, the 2 million turkeys, the 74 million mince pies and 5 million mounds of charred raisins (from rejected Christmas puddings) that are thrown away come early January. Mountains of e-waste from discarded electronic items – much of it bought as unwanted gifts and soon discarded – is projected to reach 10 million tonnes by 2020.

Just pause for a moment and picture the scale of that annual waste by the British populace. For if you combine our surplus produce with every Christian nation in Western Europe, North America, Australasia and other affluent regions, you have an appalling idea of the unnecessary ecological destruction that we collectively contribute to each year. Christmas is, after all, only an exaggerated illustration of the gross materialism that defines our everyday lives in a consumerist society.

What is more difficult to recognise is how our profligate consumption habits also directly exacerbate levels of inequality worldwide. We know that the so-called developed world – roughly 20 per cent of the global population – consumes a hugely disproportionate share of the earth’s resources, and is responsible for at least half of all greenhouse gas emissions. But behind such statistics lies a depressing reality, in which our artificial standards of living in the global North are dependent on the dire working conditions and impoverishment of millions of people throughout the global South.

In spite of the spurious claims of trickledown economics, the number of people living on less than $5-a-day has increased by more than 1.1 billion since the 1980s. The vast majority of people who live in developing countries survive on less than $10-a-day; none of their families can remotely afford the wasteful and conspicuous consumption that we consider normal.

Our personal complicity in this unsustainable global order is complex, because we are all caught in a socioeconomic and cultural system that depends on ever-expanding consumerism for its survival. Everywhere, we are besieged with messages that encourage us to ‘buy more stuff’, as profit-driven businesses increasingly seek to meet our needs (either real or constructed) through interaction in the marketplace. Our consumption patterns are often tied to our sense of identity, our desire for belonging, our need for comfort, our self-esteem.

So we are all the victims of an excessively commercialised culture, not only in a collective way through environmental harm and global warming, but also through the proximate psychological and emotional harm that in some way afflicts everyone. We experience that harm through the time-poverty of affluence; through all the pressures of living in an individualistic and market-dominated society; and through everything we’ve lost on the competitive work/consume treadmill – including our freedom for leisure, our mental space, and our community cohesion. There is also an inarticulable form of spiritual harm that arises from simply being part of this exploitative world order, in which our overconsuming lifestyles in the West are connected to the vast suffering and immiseration of people in poorer countries who we do not know, or care to know.

Clearly it is the whole system that needs to go through a radical transformation – but the challenge is deeply personal as well as political, considering that we ourselves are the constituent parts that maintain the system in its currently destructive form.

Over many decades, the basic economic problem and solution has been well articulated in a theoretical sense by progressive thinkers. Numerous reports cite the physics of planetary boundaries, demonstrating how we already require one and a half planets to support today’s consumption levels. Simply put, it is impossible to reconcile the twin challenges of ending poverty and achieving environmental sustainability, unless we also confront the huge imbalances in consumption patterns across the world, and fundamentally reimagine the economy as something different that escapes the growth compulsion.

Hence the resurgent focus on post-growth economics in a world of limits, which recognises the importance of reducing the use of natural resources in high-income countries, so that poorer nations can sustainably grow their economies and rapidly meet the basic needs of their populations. Nowhere is the case for sharing the world’s resources more obvious or urgent, than in the question of how to achieve equity-based sustainable development or ‘one planet lifestyles’ for all.

Yet our societies remain so far from embarking on this great transition, that the interrelated trends of commercialisation, inequality and environmental destruction continue to intensify year on year. What better example than the spectacle of French President Emmanuel Macron convening the ‘One Planet Summit’ this month to demonstrate international solidarity in addressing climate change, while at the same time governments were attending the resurrected World Trade Organisation talks in their continued attempts to turn the world into a corporate playground with minimal protections for the poor.

Questions of global injustice and ecological imbalance may seem far removed from our daily lives, but everyone who participates in a modern consumerist society is conjointly responsible for perpetuating destruction and divisions on an international scale. Again, our frenzied spending around Thanksgiving and Christmas time is a case in point, exemplifying how our relentless mass consumption is directly propping up an extreme market-oriented economic system, and further preventing us from embracing the radical transformations that will be required in the transition to a post-growth world. What, then, should we do?

There are already lots of answers from campaigners about how we can de-commercialise Christmas, like the buy nothing movement that advocates we ignore the conditioned compulsion to purchase luxury goods. At the least, we can practise ethical giving and support the work of activist groups and charitable organisations. For example, Christian Aid have released a witty video this year that entreats UK citizens to be aware of festive food waste in the context of global hunger, and donate £10 from Christmas food shopping - enough for a family in South Sudan to eat for a week.

Actions like these constitute small steps towards celebrating Christmas with awareness of the critical world situation, and the need for Westernised populations to live more lightly on the earth, while prioritising the needs of the less-privileged. If extended beyond the holiday season, that awareness could be translated into a mass movement that rejects the consumerist lifestyle altogether, instead voluntarily downshifting lifestyles and meeting more of our needs in ways that bypass the mainstream economy.

As proponents of the gift economy, the commons and collaborative consumption all attest, this is the long-term antidote to mass consumerism. It means we must become co-creators of alternative economic systems in which we reinvest in our communities, shift our values towards quality of life and wellbeing, and embrace a new ethic of sufficiency. It means resisting the competitive economic pressures towards materialism and privatised modes of living, thereby releasing our time and energies for cooperative activities that promote communal production, co-owning and civic engagement. In short, it means we need an expanded understanding of what it means to be human on this earth, in which we relearn how to participate in civic life and share resources at every level of society.

The holiday period during Christmas actually provides us with a unique opportunity to express the new awareness that must inform a less commercialised and more sharing-oriented world. Rather than spending all our time partaking in conspicuous consumption that has nothing to do with the message of Christ, why don’t we organise local meetings or massive gatherings for helping the poor and healing the environment, both in our own countries and further abroad?

Such an appeal to our goodwill and conscience is made in a formative essay by Mohammed Mesbahi, titled Christmas, the System and I. He exhorts us to imagine what could be done if all the money we needlessly spend on festivities and unwanted gifts was collectively pooled, then redistributed to all those who urgently need it. Indeed imagine what could be achieved if people not only donate to charities at this time of year, but also unite in countless numbers on the streets for sharing and justice on behalf of the poorest members of the human family.

If Jesus were walking among us today, writes Mesbahi, surely that is what He would call on us to do. For what cause can be of greater priority in this era of growing inequalities and planetary crisis, than the need to save the millions of people who continue to die from poverty-related causes each year? Perhaps that would be the first expression of the true meaning of Christmas in the twenty first century, when millions of people come together in constant demonstrations that call upon our governments to implement the principle of sharing into world affairs.

Adam Parsons is the editor at Share The World's Resources (STWR)

An edited version of this article originally appeared in openDemocracy Transformation

Image credit: Banksy