To mark the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations issued '30 articles on the 30 articles' that summarise this historic document. Below we republish the introduction and backgrounders about all the economic, social and cultural rights (including Article 25 on the right to an adequate standard of living), which is a central focus of our campaigning activities at Share The World's Resources (STWR).

Contents:

Introduction

Article 22: Right to Social Security

Article 23: Right to Work

Article 24: Right to Rest and Leisur

Article 25: Right to Adequate Standard of Living

Article 26: Right to Education

Article 27: Right to Cultural, Artistic and Scientific Life

Article 28: Right to Free and Fair World

Article 29: Duty to Your Comunity

Article 30: Rights are Inalienable

Introduction

It has been 70 years since world leaders explicitly spelled out the rights everyone on the planet could expect and demand simply because they are human beings. Born of a desire to prevent another Holocaust, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights continues to demonstrate the power of ideas to change the world.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted on 10 December 1948. To mark the anniversary, every day for the next 30 days the UN Human Rights Office is publishing fact sheets to put each of the Declaration’s 30 Articles into perspective. The series will attempt to show how far we have come, how far we have to go, and honour those who helped breathe life into stirring aspirations.

Although the world has changed dramatically in 70 years – the drafters did not foresee the challenges of digital privacy, artificial intelligence or climate change – its focus on human dignity continues to provide a solid basis for evolving concepts of freedoms.

The universal ideals contained in the Declaration’s 30 Articles range from the most fundamental – the right to life – to those that make life worth living, such as the rights to food, education, work, health and liberty. Emphasizing the inherent dignity of every human being, its Preamble underlines that human rights are “the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”

With the memories of both World Wars and the Great Depression still fresh in their minds, the drafters spelled out what cannot be done to human beings and what must be done for them.

Chilean drafter Hernán Santa Cruz observed that the then 58 member states of the UN had agreed that human rights derive from “the fact of existing” – they are not granted by any state. This recognition, he said “gave rise to the inalienable right to live free from want and oppression and to fully develop one’s personality.”

Because they are inherent to every woman, man and child, the rights listed in the 30 Articles are indivisible – they are all equally important and cannot be positioned in a hierarchy. No one human right can be fully realised without realising all other rights. Put another way, denial of one right makes it more difficult to enjoy the others.

The UDHR has an amazing legacy. Its universal appeal is reflected in the fact that it holds the Guinness World Record as the most translated document – available to date in 512 languages, from Abkhaz to Zulu.

The document presented to the UN in 1948 was not the detailed binding treaty that some of the delegates expected. As a declaration, it was a statement of principles, with a notable absence of detailed legal formulas. Eleanor Roosevelt, first chair of the fledgling UN Commission on Human Rights and widow of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, repeatedly stressed the need for “a clear, brief text, which could be readily understood by the ordinary man and woman.” It took 18 more years before the two binding international treaties that shaped international human rights for all time were adopted: the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights were adopted in 1966, and, together with the Declaration, are known as the International Bill of Human Rights.

Over the past 70 years, the UDHR has permeated virtually every corner of international law. Its principles are embedded in national legislations, as well as important regional treaties, and more than 90 states have enshrined its language and principles in their Constitutions. Many UN treaties, including those on the rights of women and children, on torture, and on racial discrimination, are derived from specific UDHR articles.

Today, all UN Member States have ratified at least one of the nine core international human rights treaties, and 80 percent have ratified four or more, giving concrete expression to the universality of the UDHR and international human rights.

Such progress has often been the result of heroic struggles by human rights advocates. “Human rights are not things that are put on the table for people to enjoy,” said Wangari Maathai, the late Kenyan environmental campaigner and Nobel laureate. “These are things you fight for and then you protect.”

The entire text of the UDHR was composed in less than two years, an extraordinary consensus reached at a time when the world had recently divided into the Communist East and Western blocs, when lynching was still common in the United States and Apartheid was being consolidated in South Africa.

The Syrian representative to the UN at the time observed that the Declaration was not the work of the General Assembly, but “the achievement of generations of human beings who had worked to that end.”

However, the task of crystallizing it on paper fell to a small group of drafters from varied backgrounds, including Chinese playwright Chang Peng-Chun and Dr Charles Malik, a Lebanese philosopher and diplomat. The fact that “man” in previous documents became “everyone” in the UDHR was thanks to women delegates such as Hansa Mehta from India, Minerva Bernardino from the Dominican Republic, and Begum Shaista Ikramullah from Pakistan.

The final draft was presented to the General Assembly, at a late-night session in Paris on 9 December 1948, by a descendant of slaves, the Haitian delegate Emile Saint-Lot. The draft resolution on human rights, he said, was “the greatest effort yet made by mankind to give society new legal and moral foundations.”

Even the venue for the General Assembly session was poignant. The Palais de Chaillot was the vantage point from which Adolf Hitler had been photographed, with the Eiffel Tower in the background, during his short tour of the city in 1940 – an iconic image of the Second World War.

The following day, 10 December (now celebrated annually as Human Rights Day), 58 countries brought human rights into the realm of international law, amplifying the seven references to the term in the UN’s founding Charter, which made promotion and protection of human rights a key purpose and guiding principle of the organization.

Drafters had examined some 50 contemporary constitutions to ensure inclusion of rights from around the world. Great inspiration had also been provided by the Four Freedoms proclaimed by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt in 1941. He defined essential human freedoms as freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear, and explained that “freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere.”

The UDHR advanced from rights restricted to citizens (as in the 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen) to the rights of humans, equal for all whether they belonged to a particular country or not. It also clearly repudiated the notion that states had free rein to do what they liked to people on their territory. At the Nuremberg Military Tribunal in 1945 and 1946, Nazi leaders had maintained they could not be held guilty of the newly-conceived “crimes against humanity” because, in the words of Hitler’s deputy, Hermann Goering, “...that was our right! We were a sovereign State and that was strictly our business.”

The elevation of human rights to the international level means that behaviour is no longer governed solely by national standards. And since the UDHR’s adoption, its core principle that human rights cannot be set aside for the sake of political or military expediency has been progressively absorbed not just into international law, but also into an ever expanding web of regional and national legislation and institutions, including those established by the Organization of American States and the African Union and in Europe.

Every country now is subject to external scrutiny – a concept that led to establishment of the International Criminal Court in 1998, as well as UN International criminal tribunals and special courts for Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, Sierra Leone, Lebanon, Cambodia and East Timor. There has also been a dramatic increase in the number of independent UN experts and committees who monitor implementation of the core international human rights treaties, and the UN Human Rights Council has established a system, known as the Universal Periodic Review, under which all states have their human rights record examined by each other every five years.

Praised as a living document, the UDHR stimulated movements, such as that opposing Apartheid, and opened the door to the elaboration of new rights, such as the right to development. The bar is continually being raised on some rights enumerated in the UDHR, such as the concept of what constitutes a fair trial. Newer rights treaties, such as that on disabilities, have been drafted not only by experts, but with the direct involvement of those affected.

On the other hand, 70 years on, racism, discrimination and intolerance remain among the greatest challenges of our time. Rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly – indispensable to the functioning of civil society – continue to come under attack in all regions of the world. Governments are often ready to sidestep or trample on rights in the pursuit of what they see as security, or to maintain power or sustain corruption. Despite the fact that all 193 UN member states subscribe to the Declaration, none of them fully lives up to its promise. As Nelson Mandela noted in his 1998 speech to the General Assembly marking the UDHR’s 50th anniversary, their failures to do so “are not a pre-ordained result of the forces of nature or a product of the curse of the deities. They are the consequences of decisions which men and women take or refuse to take.” A product of poor political, economic and other forms of leadership.

Yet, at the same time, the UDHR continues to provide the basis for discussion of burning new issues, such as climate change, which “undermines the enjoyment of the full range of human rights – from the right to life, to food, to shelter and to health,” in the words of former UN rights chief Mary Robinson. And the rights it asserts are at the heart of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which seek to create a better world by 2030 by, among others, ending poverty and hunger.

The first article on Article 1 of the UDHR – “All human beings are born free and equal” – will be sent to media, and placed on www.ohchr.org tomorrow, 9 November.

The UDHR has an amazing legacy. Its universal appeal is reflected in the fact that it holds the Guinness World Record as the most translated document – available to date in 512 languages, from Abkhaz to Zulu.

The document presented to the UN in 1948 was not the detailed binding treaty that some of the delegates expected. As a declaration, it was a statement of principles, with a notable absence of detailed legal formulas. Eleanor Roosevelt, first chair of the fledgling UN Commission on Human Rights and widow of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, repeatedly stressed the need for “a clear, brief text, which could be readily understood by the ordinary man and woman.” It took 18 more years before the two binding international treaties that shaped international human rights for all time were adopted: the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights were adopted in 1966, and, together with the Declaration, are known as the International Bill of Human Rights.

”Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality."

After spelling out a long list of civil and political rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) now turns to economic, social and cultural rights with Article 22 and the six following Articles. These rights, mostly developed in the 20th century, include the right to work, an adequate standard of living, education, maternity and childhood, social security, and the right to take part in cultural life.

Inclusion of these economic and social rights give effect to one of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s “Four freedoms” – freedom from want, which ismentioned explicitly in the preamble of the Declaration.

Article 22 spells out the qualities of the modern welfare state that are almost universally accepted today. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), in 1900, only 17 countries had social protection systems to support individuals and families through pensions for the elderly, disability payments for injured workers, benefits for mothers, health insurance and many other programs. Social assistance can include cash transfers, and is often referred to as a “social safety net” that helps people, especially the poor and vulnerable, cope with life’s shocks, find jobs and educate their children.

According to ILO, the number of countries with social protection systems had increased to 104 by 1946 and 187 by 2015. Around the world, about 45% of people had access to at least one social protection benefit in 2017, while 29% had access to comprehensive social security systems.

The division between economic, social and cultural rights on the one hand, and the civil and political rights on the other, has always been artificial. Without a basic education, can you effectively make use of the right to free speech? The right to work may well be undermined if you are not able to assemble in groups and have the space to voice your opinion about working conditions. And any form of discrimination can have a highly corrosive impact on a whole range of social, economic and cultural rights of the group of people discriminated against.

Interestingly, the head of the UDHR drafting committee, Eleanor Roosevelt, a long- time rights activist, did not want to impose obligations on States. The Declaration, she said, “should enunciate the rights of man and not the obligations of States.”

This view was opposed by the Soviet bloc, and Canadian delegate Ralph Maybank said that if the rights in the Declaration were achieved, “the social and international order would be good, whether it came within the framework of capitalism, communism, feudalism, or any other system.”

The issue of states’ obligations to uphold the rights set out in the Universal Declaration was in effect gradually sorted out later via the elaboration of the nine core international human rights treaties, which created binding law: in particular, the two overarching Covenants covering all rights -- the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – adopted 18 years after the UDHR in December 1966.

Article 22 asserts that economic, social and cultural rights are indispensable for human dignity and development of the human personality. This phrase appears again in Article 29, underlining that the UDHR drafters wanted not just to guarantee a basic minimum, but to help us all become better people.

That promise has not been fully realized. UN Human Rights Chief Michelle Bachelet has pointed out that “71 percent of the world’s population lacks access to full social protection. In other words, in two-thirds of the globe, societies have not been able to guarantee their people the basic means to live without fear and without feeling discriminated against or ostracized.” She added that almost two-thirds of the world’s children, 1.3 billion children, are without coverage.

In 2009, the United Nations agreed to a “Social Protection Floor Initiative” that encouraged countries to build comprehensive social security systems. Since then improvements have been seen not only in developing countries, but also many middle- and low-income countries.

Mongolia has introduced a family benefits scheme. Argentina is expanding a successful program to support pregnant women and new mothers who do not have health insurance. Thailand, Colombia, Rwanda and China have all made progress in ensuring universal access to health care.

A large number of other countries are making headway on programs to guarantee an income to senior citizens: Azerbaijan, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Cape Verde, China, Cambodia, Kosovo, Lesotho, Mongolia, Georgia, Namibia, South Africa, Thailand, Nepal, Trinidad and Tobago, and Ukraine.

Social protection floors, laid on a firm foundation of human right standards and principles, can help create a better world for all of us, says Bachelet. “We all want to see a world where all children and all adults have their basic needs met; where unemployment, injury, ill-health, old age or disability do not signal misery and hardship; where people are not left unprotected in times of crisis and disaster,” she says.

(1) Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

(2) Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

(3) Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

(4) Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

As First Lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt told striking workers in 1941 that she had always “felt it was important that everyone who was a worker should join a labour organization, because the ideals of the organized labour movement are high ideals.”

Five years later, when she headed the United Nations committee drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), she gave international labour organisations an important role in shaping the Declaration to reflect their vision of how the world should develop.

The American Federation of Labour had a full-time staff person at the UN while the UDHR was being drafted – Toni Sender, a politician and journalist who had fled Nazi Germany. Along with other labour representatives, she argued forcefully for the specific inclusion of trade union rights. Roosevelt also helped ensure that Article 23 spelled out, in four paragraphs, the right of “everyone” to work, with equal pay for equal work, and without discrimination. The right to form and join trade unions is also clearly enunciated.

In its third paragraph, Article 23 calls for “just and favourable remuneration” to ensure “an existence worthy of human dignity” for workers and their families, reflecting again a vision of a better world than the just-defeated Nazi Germany with its slave labour.

The drafters built on the work of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), one of the few institutions from the League of Nations to become incorporated into the United Nations, when it was created in 1945. Just as the UN was founded in the wake of the Second World War, the ILO had been set up in 1919 out of the ashes of the First World War. It pursued the vision that universal, lasting peace can be established only if it is based on social justice.

Latin American delegates, along with those from the Communist bloc (whose ideology espoused full employment), were instrumental in formulating the final text of Article 23. The Soviet Union, in particular, wanted not only the final terminology of “protection against unemployment,” but greater obligations on States to prevent unemployment.

Over the past 25 years, the number of workers living in extreme poverty has declined dramatically, but unemployment is still a major issue, with more than 204 million people unemployed around the world in 2015.

Equal pay for equal work is still a dream in most countries. More generally, women face enduring obstacles in achieving economic empowerment. According to the World Bank, about 155 countries have at least one law that limits women’s economic opportunities, while 100 States place restrictions on the types of jobs women can do. In 18 States, husbands can dictate whether their wives can work at all.

Child labour also still exists in many countries. The ILO says 152 million children are engaged in mentally, physically or socially dangerous work that prevents them from getting an education. In Africa, one in five children is a child labourer, with smaller proportions in other parts of the world. Globally, around half of the victims of child labour are between five and 11 years old.

One of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is devoted to decent work and economic growth. The UN hopes to eradicate forced labour, slavery and human trafficking, and achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men by 2030.

Unfortunately, by many measures, the world is slipping back, not progressing, in protecting workers’ rights. The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) promotes and defends workers' rights. In its 2018 Global Rights Index, it say an increasing numbers of countries are chipping away at labour protection and persecuting advocates for workers' rights in an effort to undermine trade unions and create a climate of intimidation among workers and unions.

In 2018, it reported, governments in three of the world's most populous countries - China, Indonesia and Brazil – passed laws that denied workers’ freedom of association, restricted free speech and used the military to suppress labour disputes.

While workers have the right, on paper, to freedom of association, in 2018, 92 out of 142 countries surveyed by the ITUC excluded certain categories of workers (for example, part-time employees) from this right. At the same time, many consumers, largely as a result of sustained advocacy by civil society organizations, are becoming more aware of the issues covered in Article 23, such as being paid a living wage and working in safe conditions.

In addition to States, all companies, whatever their size or sector, have a responsibility to respect core labor rights such as the right to work, and the right to freedom of association and collective bargaining. This responsibility applies across a company’s global value chain and follows from the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 2011.

UN Human Rights Chief Michelle Bachelet argues that there is a “colossal” cost to violations of economic and social rights. Excluding people with disabilities from the work force, for example, can cost economies as much as seven percent of GDP.

“Evidence from many business sectors indicates that respecting human rights can have a direct impact on a company’s bottom line,” she says. Consumers also have a role to play in examining the “human rights issues related to the goods they buy and the services they pay for.”

Article 24: Right to Rest and Leisure

"Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay."

In 19 crisp words, Article 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights presents the flip side of the right to work articulated in Article 23 – the right not to be over- worked. It enshrines the right to limited working hours and paid holidays, but as Cuban drafter Pérez Cisneros said in the late 1940s, it should not be interpreted as “the right to laziness.”

Even in the 19th century, there was recognition that working excessive hours posed a danger to workers' health and to their families Limitations on working hours and the right to rest are not explicitly mentioned in any of the core human rights Conventions, but had been enshrined in the very first treaty adopted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1919, which applied an eight-hour day and 48-hour week to industry.

Article 23 owes much to the contributions of Latin American countries to the drafting process between 1946 and 1948. In the mid-1940s, almost all countries in this region had democratic governments, and their constitutions were rich with social and economic rights, including provisions for annual holidays and other forms of paid leave.

These constitutions were examined as inspiration for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), and they met with the approval of the Communist bloc. As the Yugoslav drafter Vladislav Ribnikar said, “the right to rest without pay meant nothing.”

Linked to reasonable working hours, leisure time and paid vacations is the right of each person to self-development and education. This provision is one of many places where the UDHR aims to ensure the full development of people’s personality.

Safeguarding workers’ physical and mental health is not only compassionate, it helps to ensure high productivity. On the other hand, over-work – too many hours and past one’s capacity – can be fatal.

In Japan, there is a word for “overwork death” – Karōshi (過労死) – first identified in 1969. Not only confined to Japan, karōshi deaths are most often caused by heart attacks and strokes due to stress and a starvation diet.

The ILO reports the case of a man working in a major snack food processing company in Japan, who put in as many as 110 hours a week, and died from a heart attack at the age of 34. In another case, a widow received workers’ compensation 14 years after the death of her 58-year-old husband, an employee of a large Tokyo printing company, who had worked 4,320 hours a year, including night work -- the equivalent of 16 hours out of every 24.

In addition to over-worked employees, there is another group who, in many countries, harder than they ever thought possible – often in unsafe or unhealthy conditions – and still find themselves sinking into debt and poverty. These are migrants, regardless of their status: both undocumented and those with residence rights.

A 1990 treaty, the Convention on the Protections of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, aims to protect the labour and related rights of non- nationals, including their right to rest and leisure. However, it has so far only been ratified by 54 states – mostly those which are producing migrants, rather than those that receive them.

However, important regional bodies are also working to uphold the employment rights of migrants. In the case of an undocumented Mexican worker in the U.S. who was fired for attempting to organize workers, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights stated that he should still receive the back pay owed to him, and affirmed that governments have the obligation to ensure the rights of everyone within their jurisdiction, including labour rights.

Governments everywhere have a legal obligation to ensure the right to safe and healthy working conditions, the right to limited working hours and paid holidays, but these rights have been under assault in some countries since the global recession of 2008.

In a number of developed countries, steady jobs – with benefits, holiday pay, a measure of security and possible union representation – are increasingly giving way to contracts.

As one expert put it, in today’s world, workers seem like “nothing so much as teenagers lending a hand in an affluent family business.” Instead of old-fashioned employment with full labour protections, “there is now getting some experience, earning a bit of money, or helping out when the orders come in.”

The concept that employees are trying to earn a living wage, and that their employers have obligations toward them, is being steadily eroded in some countries where it was well-established, even as it advances haltingly in others where it has never fully taken hold.

Companies themselves have a responsibility to respect the right to leisure as part of their responsibilities under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. This responsibility applies throughout their supply chains, and it means that, as part of its ‘human rights due diligence,’ a company should consider whether any of its activities or operations are resulting in excessive working hours for employees.

Article 25: Right to Adequate Standard of Living

(1) Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

(2) Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights covers a wide range of rights, including those to adequate food, water, sanitation, clothing, housing and medical care, as well as social protection covering situations beyond one’s control, such as disability, widowhood, unemployment and old age. Mothers and children are singled out for special care.

This Article is an effort to secure freedom from want, based on U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s famous vision of four freedoms. In a speech in 1941, he looked forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms: the freedom of speech and expression, the freedom to worship God in his own way, freedom from want and freedom from fear. After Roosevelt’s death and the end of World War II, his widow Eleanor often referred to the four freedoms as head of the committee drafting the UDHR.

The phrase “freedom from fear and want” appears in the Preamble to the UDHR, and Article 25 tells us what that should look like. It is further fleshed out in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, part of the trio of instruments that comprise the Bill of Rights, along with the UDHR.

After two Articles that looked after the rights of working people, Article 25 emphasizes that “everyone” has social and economic rights. There is a level below which nobody should fall. In language that is now old-fashioned, yet expresses a progressive notion, this Article specifies that all children are guaranteed the same rights “whether born in or out of wedlock.” Article 25 also forms the basis for current efforts to address the particular challenges facing millions of older women and men around the world.

The first requirement listed in Article 25 as being necessary for “a standard of living adequate for... health and wellbeing” is food. A former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Jean Ziegler, observed that “the right to food does not mean handing out free food to everyone.” However, governments are obliged not to prevent access to adequate food by, for example, forced eviction from land, destruction of crops or criminalization of poverty. Governments also have to take adequate steps to ensure that private sector activities do not impinge on people’s right to food. And, similarly, private water services cannot compromise equal, affordable and physical access to sufficient, safe and acceptable water supplies.

Many experts say the world produces enough food to feed itself. But some 815 million people continue to suffer from chronic hunger because of unequal distribution of wealth and resources: they are too poor to buy food, do not have land to produce their own food or face a variety of other obstacles that could be resolved.

Poverty is both a cause and a consequence of violations of human rights, and places many other rights listed in the UDHR out of reach. The World Bank and World Health Organization reported in 2017 that at least half of the world's population (some 3.8 billion people) is too poor to get essential health care services, inconsistent with the right to health spelled out in Article 25. They also said nearly a billion people spend 10 percent or more of their household income on health expenses for themselves, a sick child or another family member. For almost 100 million people, these expenses are high enough to push them into extreme poverty, an unacceptable and unnecessary situation, they said.

Extreme poverty is more than just a lack of sufficient income. For the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, extreme poverty involves a lack of income, a lack of access to basic services – health, schooling and living conditions – and social exclusion. By this measure, over 2.2 billion people – 30 per cent of the world’s population – are either near or already living in poverty.

The current Special Rapporteur, Philip Alston – tasked with advancing the eradication of such poverty – has pointed out that extreme poverty is not confined to developing countries. Government policies can entrench high levels of poverty and inflict “unnecessary misery” in even the richest countries in the world.

“I have spoken with people who depend on food banks and charities for their next meal, who are sleeping on friends’ couches because they are homeless and don’t have a safe place for their children to sleep,” Alston said after a 2018 visit to the UK. He said he also met people “who have sold sex for money or shelter, children who are growing up in poverty unsure of their future.”

Where national governments step back from international obligations (such as the United States’ announced withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change), cities increasingly are stepping in to fill gaps. The global South has led the movement to establish “human rights cities,” and York has followed this lead to become the first human rights city in the UK.

In a 2017 declaration, it embraced “a vision of a vibrant, diverse, fair and safe community built on the foundations of universal human rights.” It selected five human rights priorities: the rights to education, housing, health and social care, a decent standard of living, and equality and non-discrimination. York’s first four priorities are among the social rights found in article 25, while the fifth – equality and nondiscrimination – lies at the very heart of the UDHR and of all social rights.

Article 26: Right to Education

(1) Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

(2) Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

(3) Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

In 2002, when the Kenyan government announced free primary school education for all, Kimani Ng'ang'a Maruge decided to enroll in Grade One. What’s unusual about that? He was an 84-year-old great-grandfather. A photo on the front page of a Kenyan newspaper showed him sitting at a tiny desk next to six-year-olds, wearing a uniform he had fashioned for himself, complete with regulation shorts.

Maruge said he wanted to learn to read the Bible to find out if preachers had been quoting it correctly all his life. He lived five more years, was certified by the Guinness Book of World Records as the oldest person to enroll in primary school, and was taken to New York to address the UN Millennium Development Summit on the importance of free primary education.

Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) makes universal free primary education compulsory, and is usually thought of as a right about children. But as Maruge showed, people of any age can seek and benefit from education and literacy. Not only was a movie made about his life, but his story inspired many dropouts in Kenya to return to school and complete their education.

This right is further enshrined in various international conventions, in particular the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (which has been ratified by every country except the United States). In Article 26 of the UDHR, we see the right to “full development of the human personality,” which also appears in Articles 22 and 29. It is clear the drafters saw this term as a way of summarizing many of the social, economic and cultural rights in the Declaration, and there has been an increasing focus by international bodies on the role of education in empowering individuals – both children and adults.

Unusually for the UDHR’s long list of rights, this one has in some respects been widely achieved. More children around the world have access to education today than ever before, with rates of primary school attendance for girls rising to parity with boys in some regions. The overall number of children out of school worldwide declined from 100 million in 2000 to an estimated 57 million in 2015.

The World Bank and OECD estimate that in 1960, only 42 percent of people in the world could read and write. By 2015 that figure had risen to 86 percent. Some countries – Andorra, Azerbaijan, Cuba, Georgia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Russia, Slovenia and Tajikistan – have literacy rates at or near 100 percent.

However, literacy is a moving target. Many countries now aspire – in accordance with the aims laid out in Article 26 – to make secondary education free and universal, and some aim for more widespread tertiary education. “Literacy” is also being expanded in many places to include the ability to use numbers, images and computers as well as language, and to encompass other ways of communicating and gaining useful knowledge.

But these positive figures mask the fact that progress has also been very uneven, due largely to inequalities and discrimination, with the right to education continuing to be denied to children from marginalized groups and those living in the worst forms of poverty and deprivation. The most disadvantaged children have continued to be left behind, for example children with disabilities, indigenous children and stateless children – and especially girls who belong to these groups.

Despite the steady rise in literacy rates over the past 50 years, there are still 750 million illiterate adults around the world, most of whom are women. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a key opportunity to ensure that all youth and most adults achieve literacy and numeracy by 2030, with SDG 4 in particular addressing both access to, and quality of, education.

In many places, girls are prevented by social and cultural practices from getting an education. In 43 countries, mainly located in Northern and sub-Saharan Africa and Western and Southern Asia, young women aged 15 to 24 years are still less likely than young men to have basic reading and writing skills.

A lack of education, especially of girls, has been demonstrated to have an enormous impact on society at large, on health, and on the economic development of countries, not least because deprivation of the right to education often spans generations, as it perpetuates entrenched cycles of poverty. Education is perhaps the most powerful tool available to pull marginalized children and adults out of poverty and exclusion, making it possible for them to play an active role in the processes and decisions that affect them.

Education as a fundamental human right is essential for the exercise of all other human rights. It promotes individual freedom and contributes definitively to a child’s broader empowerment, wellbeing and development, not least by ensuring that they are equipped to understand and claim their rights throughout their lives.

Perhaps the most prominent advocate of girls’ education is Malala Yousafzai, a Pakistani activist and the youngest ever winner of a Nobel Prize. When she persisted in attending school in her native Swat Valley after the local Taliban had banned girls from school, Malala and two other girls were shot by a Taliban gunman in an assassination attempt.

Undaunted, she continued to pursue her activities after her recovery. “With guns you can kill terrorists, with education you can kill terrorism,” she says.

Article 27: Right to Cultural, Artistic and Scientific Life

(1) Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

(2) Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

The monumental Buddhas of Bamiyan, statues 10 to 16 storeys high hewn from sandstone cliffs, inspired reverence and awe in central Afghanistan for 15 centuries – until the Taliban blew them to smithereens in 2001. In 1993, during the Bosnian War, Stari Most, the gracefully-arched Ottoman bridge that gave the town of Mostar its name, was deliberately targeted by a barrage of artillery shells, sending the 427-year- old protected monument into the Neretva River.

When attacking armed groups want to crush the morale of civilians or opposing forces, they often deliberately destroy symbols of cultural heritage.

Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) helped lay the ground for this to be recognized as a war crime, and in a landmark judgment in September 2016, the International Criminal Court declared Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, a member of the Ansar Dine armed group operating in Mali, guilty of the war crime of attacking historic and religious buildings in Timbuktu. He was sentenced to nine years in prison.

It was the first time the destruction of cultural sites had been prosecuted as a war crime at the ICC, giving hope that more such court cases would follow – especially for members of ISIS who carried out wanton targeted destruction of a wide range of cultural and religious monuments in territory it once held in northern Iraq and Syria.

The ICC Al-Mahdi case was the first time someone had been charged with the destruction of cultural heritage as a stand-alone war crime. Other tribunals have charged individuals with the criminal destruction of cultural heritage sites – including the destruction of the bridge in Mostar -- but only as an additional offence attached to more established war crimes such as summary executions and torture.

All but one of the historic mausoleums Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi had helped destroy UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova has described this war tactic of tearing communities apart as “cultural cleansing.”

According to the Special Rapporteur on cultural rights, Karima Bennoune, “the destruction of cultural property with discriminatory intent can be charged as a crime against humanity, and the intentional destruction of cultural and religious property and symbols can also be considered evidence of intent to destroy a group within the meaning of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.”

Article 27 says everyone has the right to freely participate in the cultural life of the community, to share scientific advances and its benefits, and to get credit for their own work. This article firmly incorporates cultural rights as human rights for all. They relate to the pursuit of knowledge and understanding, and to creative responses to a constantly changing world. A prerequisite for implementing Article 27 is ensuring the necessary conditions for everyone to continuously engage in critical thinking, and to have the opportunity to interrogate, investigate and contribute ideas, regardless of frontiers.

One of the great unachieved goals of the UN’s ill-fated predecessor, the League of Nations, was protection of minority groups. Charles Malik, the Lebanese drafter who made important contributions to the UDHR as it was drawn up between 1946 and 1948, strongly defended the rights of minority groups. He wanted to make sure members of minority communities were protected from extreme forms of assimilation. In the end, the Declaration did not include a separate article devoted to the rights of members of minority groups, but the term “culture” is understood to also refer to “the way of life” of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities. It is about preserving diversity.

Article 27 is closely linked to Articles 22 and 29 in asserting that economic, social and cultural rights are indispensable for human dignity and development of the human personality. Taken together, they show the UDHR drafters’ determination not just to guarantee basic minimum standards, but to help us all become better people. All three rights were subsequently enshrined in other international treaties including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, ratified by 169 states.

Under a separate topic covered by Article 27, lies a concern that everyone’s right “to share in scientific advancement and its benefits” has been attacked in recent years, particularly in debates over climate change and disease.

In some circles, the issue of whether humans cause climate change, or whether climate change even exists, is treated as a matter of personal belief rather than rigorous science. And scientific publications have expressed alarm at what one described as “a rise of populist antagonism to the influence of experts.” In 2018, a group of 58 experts wrote an open letter condemning a misplaced sense of balance creating “a false equivalence between an overwhelming scientific consensus and a lobby, heavily funded by vested interests” that intentionally sows doubt. Climate change is real, they declared: “We urgently need to move the debate on to how we address the causes and effects of dangerous climate change” because the alternative, they said, will be “catastrophic.”

Scepticism about science, or pseudoscience, can cost lives, as tragically illustrated by pressure placed on parents not to vaccinate their children against diseases which had greatly diminished after decades of successful vaccination campaigns. The World Health Organization says 21 million lives were saved by the measles vaccine between 2000 and 2017. But between 2016 and 2017, reported measles cases jumped 30 percent, in part because of parents refusing to use the vaccine because of false claims about its risks. In 2017 alone, WHO estimates 110,000 children died from the virus.

In the same way, putting commercial interests before the common good can also lead to loss of life, when patent policies and subscription prices for specialist publications make knowledge and its application inaccessible to those who need it. This is true in medicine, but also in food production, architecture, engineering and many other spheres.

Article 28: Right to a Free and Fair World

"Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized."

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted in a period, 1946-1948, that was simultaneously filled with optimism, yet overshadowed by the preceding thirty years of disaster – the Great Depression and two world wars. In the view of the drafters of the UDHR, a world at peace was essential for respect for human rights and to create opportunities for everyone to improve their lives.

Article 28 says, in its entirety, that “everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.”

French jurist and judge René Cassin, one of the guiding thinkers behind the Declaration, saw this Article as the first of the crowning trio that bind the whole Declaration together. He used an architectural analogy to describe the UDHR, comparing it to the portico, (or entrance porch) of a classical Greek temple – with a foundation, steps, and four columns surmounted by a triangular pediment on top (Articles 28, 29 and 30).

Cassin envisioned Articles 1 and 2 as the foundation blocks, comprising the fundamental principles of dignity, equality, liberty and solidarity, The Preamble – explaining why the Declaration is needed – he saw as the steps. Articles 3-27 are four columns: firstly the fundamental rights of the individual; then civil and political rights, followed by spiritual, public and political freedoms; with the fourth pillar devoted to social, economic and cultural rights. Articles 28-30 – concerned with the duty of the individual to society, and the prohibition of privileging some rights at the expense of others, or in contravention of the purposes of the United Nations – form the triangular pediment of Cassin’s Greek temple.

For decades after the adoption of the UDHR in 1948, there was general acceptance that one of the principal ways to achieve “a free and fair world” – and maintain peace – was through international cooperation. In 1966, countries came together to adopt the other two essential documents that join the UDHR in forming the international Bill of Rights, namely the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Even during the Cold War, during which the Soviet Bloc and Western countries led by the United States struggled for world domination, further human rights treaties were adopted: the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (in 1965), The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979), the Convention Against Torture (1984) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). All of these binding laws were firmly rooted in the principles laid down in the Universal Declaration, years earlier.

In recent years, however, belief in multilateralism has started to fray, as some countries overtly assert their national self-interests over the welfare of humankind in general. As Human Rights Chief Michelle Bachelet puts it: “The grave danger we see today is the attempts to undermine and even discard the entire multilateral framework that was designed to protect human rights and prevent conflict. Increasing numbers of leaders no longer pretend to care about human rights, and seek to clamp down on civil society, often using national security as the pretext.”

The question facing world leaders, as IMF Chief Christine Lagarde sees it is: “Do we cooperate as a global family or do we confront each other across the trenches of insularity? Are we friends or are we foes?” The answer, she suggested is “a renewed commitment to international cooperation; to putting global interest above self-interest; to multilateralism.”

Aggressive nationalism has an impact on respect for human rights. The right to a free and fair world implies the critical need to promote equality of opportunity and outcome within and between countries: “Inequality and discrimination are some of the defining challenges confronting the world today, a world that is wealthier but also more unequal than ever before” said Mr. Saad Alfarargi, the UN expert on the right to development.

UN human rights bodies and independent human rights experts, important tools for realizing the international order that Article 28 speaks of, are increasingly under attack, as – sometimes – are people who cooperate with them. The UN Special Rapporteur on Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, who has herself been threatened, informed the General Assembly in 2018 that people who had spoken to her during her visits to Myanmar had faced serious reprisals. An experience shared by a number of other UN Special Rapporteurs, in flagrant disregard of states’ obligation to cooperate with mechanisms set up by states themselves, in the form of the Human Rights Council.

The failure of countries to cooperate could destroy our planet, UN Secretary General António Guterres has warned. What is missing in tackling climate change, he said in 2018, "is the leadership, and the sense of urgency and true commitment to [a] decisive multilateral response."

French President Emmanuel Macron has also called for “dialogue and multilateralism” to resolve the world’s crises, saying that “nationalism always leads to defeat.” Speaking to the UN General Assembly in 2018, Macron urged his fellow world leaders not to “accept our history unraveling,” adding: “Our children are watching.”

Article 29: Duty to Your Comunity

(1) Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.

(2) In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.

(3) These rights and freedoms may in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

So far, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) has concentrated on rights that every person has simply by virtue of being born human. Now Article 29 says the corollary of rights is duties. We all have a duty to other people, and we should protect their rights and freedoms.

Fernand Dehousse, the Belgian representative to the United Nations while the UDHR was being drafted, said that Article 29’s first paragraph “quite properly established a sort of contract between the individual and community, involving a fair exchange of benefits.”

Article 29 also says rights are not unlimited. If they were, social balance and harmony would be impossible. It seeks to link the exercise of rights with the interests of the world community, which the United Nations had been set up in 1945 to represent.

Two early draft versions included these provisions: "These rights are limited only by the equal rights of all," and "Man is essentially social and has fundamental duties to his fellow-men. The rights of each are therefore limited by rights of others."

Neither survived in its original wording, but teh meaning they convey is close to the final version, which says "in the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others..."

At an individual level, it has long been accepted that we ought not to infringe on the rights of others while exercising our own rights. As the well-known 1919 formulation by a judicial philosopher put it: “Your right to swing your arms ends just where the other man’s nose begins.”

What is less well known is that the Declaration of rights could well have been a “law of human rights and duties.” Canadian law professor John Humphrey, who was also the first director of the UN Human Rights Division, scoured dozens of national constitutions for inspiration for his first draft of the UDHR. His original draft said the exercise of rights was limited by the “just requirements of the State.” As we shall see, that idea was viewed as problematic by the other drafters.

Eight months before the UDHR was adopted on 10 December 1948, the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man had been agreed in Bogota, Colombia.

It was a seminal document in the development of international protection of human rights. Some of its 28 provisions, such as the right to a fair trial, are also found in the UDHR. Others – like the duty of children “to honour their parents always” – are not.

At the time, Latin America was largely democratic, and military dictatorships were decades in the future. Even so, delegates from other countries saw the danger that governments might use such "duties" to limit human rights in unpredictable, unacceptable ways, and declined to accept the concept.

They were particulary concerned about the duties in the American Declaration "to obey the law and other legitimate commands of the authorities of his country," and "to render whatever civil and military service may require for its defence and preservation."

This, they perceived as opening a Pandora's Box that might unravel the whole delicately interlaced structure of individual rights and freedoms.

What would happen if these duties came into conflict with human rights of expression, association, religion, and political participation? The UDHR drafters feard some of the language in the American Declaration (and even some of the language that appeared in early drafts of the UDHR) would allow States to impose any limitations they liked on the rights of individuals.

Since 1948, international jurisprudence has made it clear that some rights cannot be limited at all, and others can be limited only under certain conditions: restrictions can only be prescribed by law; they must serve one of the purposes listed by international law; and they must be proportional to the purpose in terms of their severity and intensity.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet has warned that "increasing numbers of leaders no longer pretend to care about human rights, and seek to clamp down on civil society, often using national security as the pretext." In so doing, they are distorting the notion, contained in Article 29, that individual rights may be legally constrained by "the just requirementes of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society."

Not only that, they are ignoring the very last words of Article 29 which stresses nothing should occur which is "contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations."

Article 30: Rights are Inalienable

"Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein."

A judge at the European Court of Human Rights, Elisabet Fura-Sandström, was asked which of the rights in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is most important. “Life? Freedom? Democracy? I hope I never need to choose,” she replied.

This idea that rights are indivisible is at the heart of Article 30. All the rights in the UDHR are connected to each other and are equally important. They all have to be followed, and no one right trumps the others. These rights are inherent to every woman, man and child, so they cannot be positioned in a hierarchy, or exercised in isolation.

As we saw when we discussed Article 28, the Declaration can be imagined as the portico of a Greek temple. Take away any one element, and the portico collapses. In this analogy, suggested by UDHR drafter René Cassin, it is Articles 28-30 that bind the whole structure together.

Article 30 has been called “limits on tyrants.” It gives all of us freedom from State or personal interference in the rights in all the preceding Articles. However, it also stresses that we may not exercise these rights in contravention of the purposes of the United Nations. Working in the shadow of the Second World War, the drafters wanted to prevent Fascists’ returning to power in Germany by, for example, taking advantage of freedom of expression and freedom to stand for election at the expense of other rights and freedoms. They were acutely aware that many of the atrocities inflicted by Hitler’s regime were based on an efficient legal system – but with laws that violated basic human rights.

Drafters were looking for an international legal framework to guard against excesses of individual countries, and to prevent another war or Holocaust. States that treat their own citizens well, they believed, were less likely to have aggressive designs on other countries.

What they produced was an astonishing achievement. In the midst of recovery from war, at the outset of the Cold War, with the United Nations in its infancy, the drafters managed to agree on a text that transcended differences in language, nationality and culture – not completely, but to an extent unprecedented in international relations.

The magnitude of this achievement is underscored by the fact that it took a further 18 years to reach agreement on the other tow documents that, with the UDHR, make up the international Bill of Rights: The international Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. And then 11 additional years until enough countries ratified the to bring them into effect.

In 1948, most regarded the Declaration as creating moral but not legal obligations. However, Belgian prime minister Count Carton de Wiart believed the UDHR had not only “unprecedented moral value,” but also “the beginnings of a legal value.” Cassin, one of the chief architects of the UDHR, believed it would have legal standing because it was the first declaration by an international group having its own “legal competence.”

Because it is not a treaty, The Universal Declaration does not directly create legal obligations for countries. However, as an expression of the fundamental values which are shared by all members of the international community, it profoundly affected the development of human rights law. Its provisions were further elaborated by a number of other international instruments, including The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979), The Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) and The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989).

Some argue that because countries have consistently invoked the Declaration over decades, some of its components have grown into customary international law, and many academics and lawyers are of the view that they are therefore binding, for example the total prohibition of torture. The UDHR has been an extraordinarily flexible foundation for broadening and deepening the concept of human rights. Today it is embedded in laws, and in the DNA of regional intergovernmental organizations and of NGOs and human rights defenders everywhere. But the fact that some lawyers view the Declaration as legally binding does not, of course, mean it is uniformly observed.

Yet, over the last 70 years, there has been remarkable progress. “Globally, human life has improved immensely, including in health and education, “ says UN Human Rights Chief Michelle Bachelet. “Governments have grown in their understanding of how they should serve their people. businesses are more aware of their responsibilities towards the protection of human rights and prevention of violations.”

Perhaps Eleanor Roosevelt, the tireless human rights champion who steered the drafting process, expressed best the aims and impact of the Declaration. Where, she used to ask audiences, do universal human rights begin? Her answer: “In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Such are the places where every man, woman and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, and equal dignity, without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.”

Today, 70 years on, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the most translated document in the world, is still a vibrant force for all those people in villages and cities throughout the world who, without necessarily knowing that is what they do, struggle to make human rights a reality in their daily lives in their own communities.

Further resources:

To view the full series of fact sheets, visit: https://www.standup4humanrights.org/en/download.html

Original source: Office of the United Nations High Commssioner for Human Rights

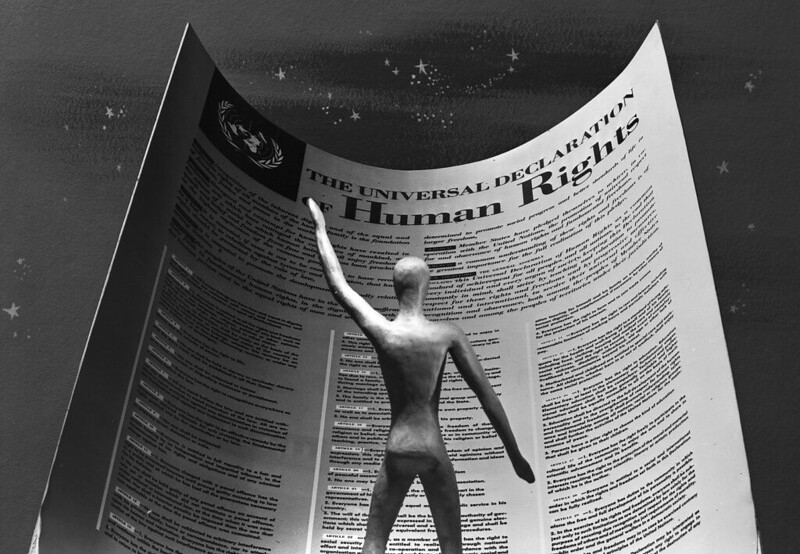

Image credit: Some rights reserved by United Nations Photo, flickr creative commons